Text: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

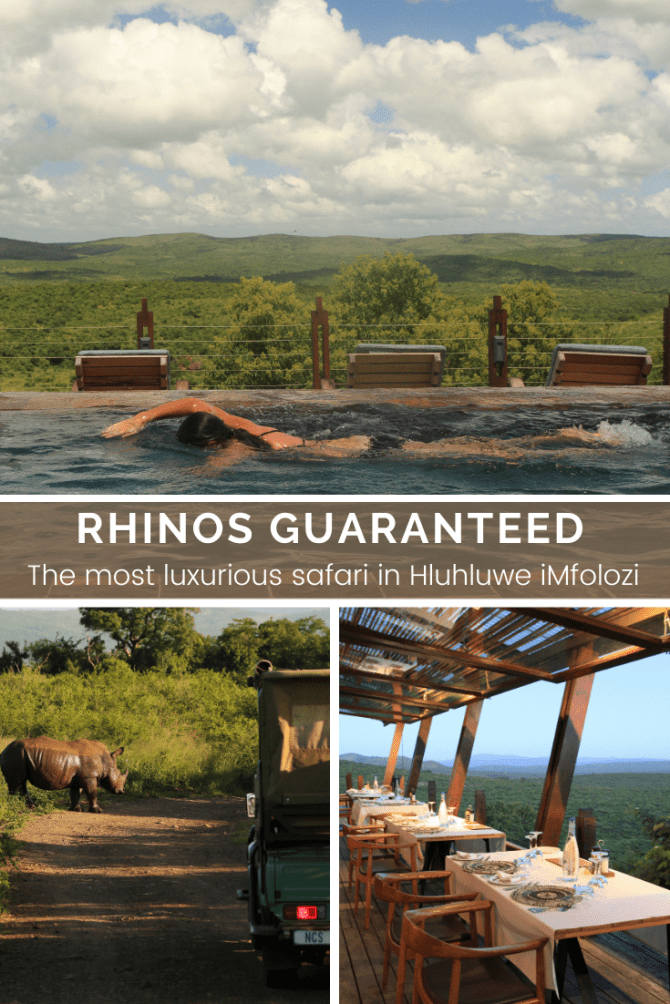

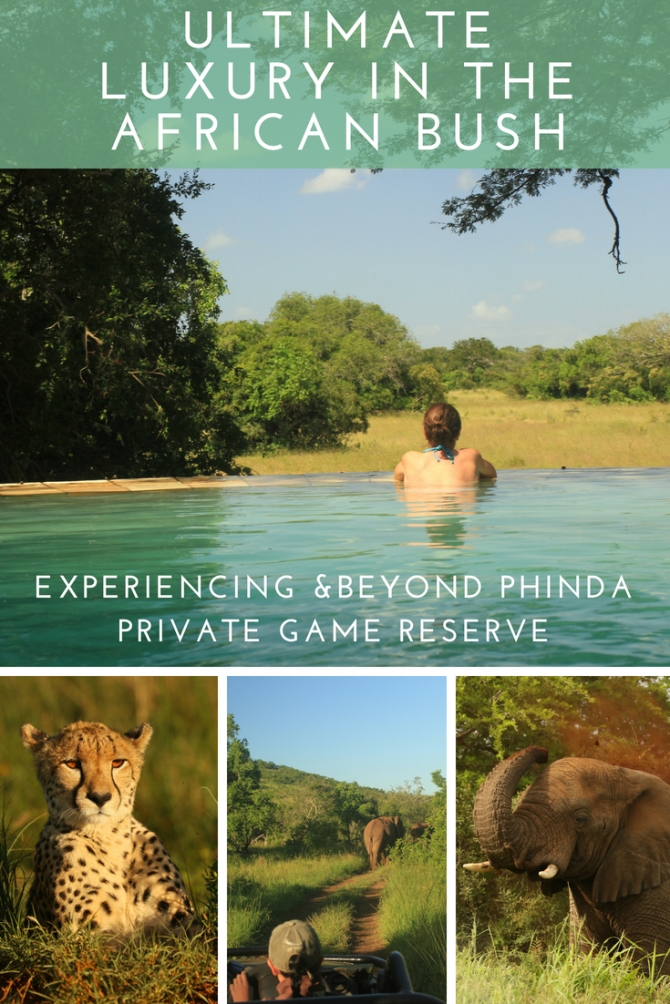

The cold water of the rain shower feels good: it has been a long drive with the very last stretch on a hilly rough dirt road in the burning sun before we eventually arrived at the lodge. As I am contemplating the view on the endless rolling hills in my favourite wilderness of South Africa from the shower, I am startled. I jump out onto the large outdoor private deck of our villa and with my hands – and everything else for that matter – still wet, I grab my binoculars: “rhinos!” I observe three of these prehistoric animals with their so coveted horns roaming the opposite green slope: a calf which I estimate no older than a few months, its mother and another white rhino that could be the calf’s older sibling. I feel extremely privileged to witness this scene as their numbers are dangerously plummeting and rhinos are on the verge of extinction, being poached to feed the insatiable Chinese market. For sure, the Isibindi Rhino Ridge Safari Lodge that sits at the edge of the Hluhluwe iMfolozi game reserve in Kwazulu Natal, is well named! If the head of Isibindi Africa Trails, Nunu Jobe, is as pertinently nicknamed, I hardly dare imagining what a walk in the African bush with the “Rhino Whisperer” holds for me…

Bookmark, or save this pin for later!

We meet Nunu, our trail guide, in the comfortable lounge area of the lodge as we are savouring our early afternoon high tea. He greets us with the smiley eyes of the ones who live their passion. The Rhino Whisperer and founder of Isibindi Africa Trails checked out a few tracks on his way to the lodge, and moving onto the expansive main viewing deck he is pointing to the area where we are about to step into the bush amongst the famous Big 5 (rhinoceros, buffalo, lion, leopard and elephant). His excitement is contagious and we quickly fill up our aluminium bottles with filtered water in the environment-conscious lodge before following him.

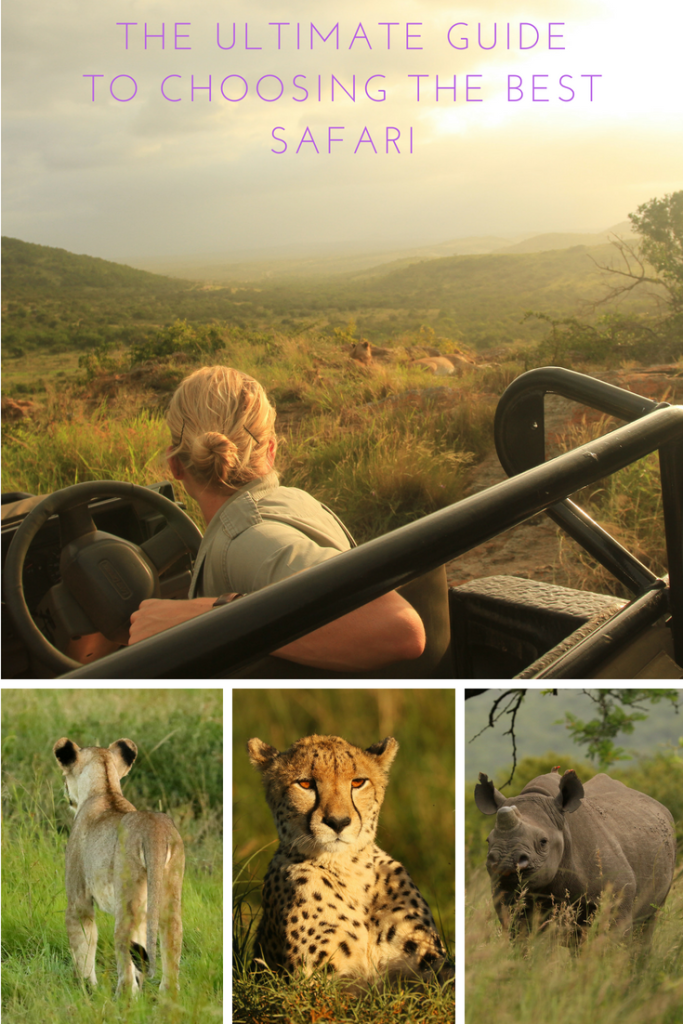

After a few minutes in an open game drive vehicle and a safety briefing, we climb out of the 4×4 Landcruiser, an otherwise unthinkable move during the daily sunrise and sunset game drives. Nunu and his back up guide Luke are loading their rifles. To answer my interrogative look, Nunu explains: “It is mandatory for us in South Africa to carry a riffle on bush walks. So far, we have only used it on the shooting range, and we intend to keep it this way.” It is very unlikely that shooting an animal is the only way out of a tensed situation in the wild. Reading the bush well by studying tracks, factoring in the wind and adapting to animal behaviours after years of experience, Nunu has always kept his guests out of harm’s way while providing them with the fulfilling and intense experience of walking the same ground at the same level as wildlife.

We all have to use all of our senses on this outing: for Nunu and Luke it is a requirement; for us, it is to live this rare moment to the fullest and reconnect with nature. “There is another sense that we all have but often ignore which we will listen to when walking in the wild…” Nunu adds enthusiastically with a grin. “Instinct!” We will need to adapt our route constantly based on the animals we come across. “Tune into your instinct and you will know when something is going to happen. There is no good or bad here, it is just happening.” Internally, I pause to reflect on his statement that I find highly insightful. In a society where judgement is omnipresent, here in the wild, guilt, fairness and anthropomorphism are totally irrelevant. Nature follows its way and the only kind of interference that feels mandatory is to repair what humans have damaged [I recall the zebra that I saw this morning on our way to the lodge, with a snare installed by poachers cutting deep in its neck*]. This walk in the wild is turning into a deep and meditative experience, just seeing things the way they are.

Nunu quickly texts the anti-poaching unit which patrols the park day and night to let them know our position. These highly trained guards who face fearless and heavily armed rhino poachers are always on high alert, and there is no need for them to waste their thin resources on us.

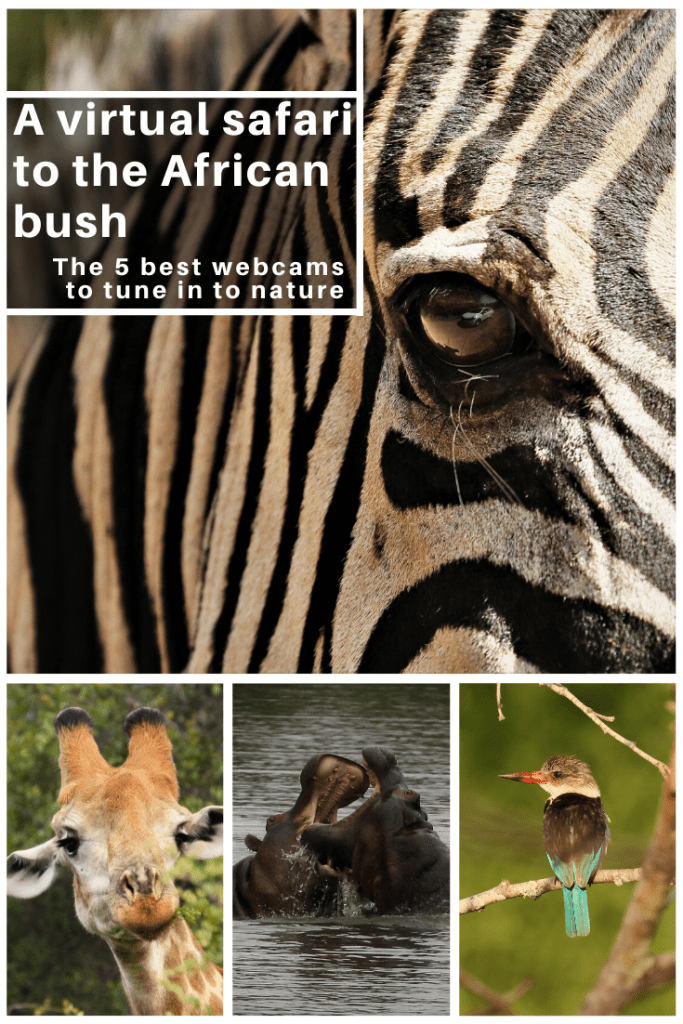

Off we go. Before we even realise, Nunu has already spotted a white rhino grazing not far from us and flawlessly predicts in which direction the rhino is moving. Silently, he motions us to follow him, past a few waterholes where a dazzle of zebras and a family of warthogs hang out, towards grazing herds of wildebeest, buffalos and impalas. Observing these animals from a humming game drive vehicle is already very special, and instead of looking down on them from the safety of the 4×4, meeting them at the same level in silence adds a whole new perspective and depth to it. Mimicking our guides and breaking our human shape, we kneel to observe better. Eye to eye with the elegant impalas, slightly nervous wildebeest and unpredictable buffalos, we spend some precious and intense moments during which we are cautiously observed by hundred of eyes. Deep inside, this encounter resonates. It has been almost two centuries since these animals have been segregated for their own protection, and kept in large yet fenced parks, and we are not so used to being in such proximity anymore. Continuing on foot, slaloming around elephant, buffalo and rhino dung, Nunu motions us to a halt by a boulder partially covered in dry mud. “This is a scratching post for rhinos”, he explains, his low voice breaking the silence. “Even though the red-billed oxpecker you often see on them takes many of their ticks away, they still need to get rid of these parasites: they take a mud bath to suffocate them, and then rub their thick skin against a trunk or a stone like this to finish the job.”

Nunu knows precisely where to go in order to get a close encounter without being in the rhinoceros’ way. It looks like the rhino which Nunu has spotted earlier is on time for his appointment with the Rhino Whisperer as the massive 2.5-ton bull heads straight into our direction, head down continuously grazing and sniffing the ground. The peaceful-looking white rhino is one of the Big 5, meaning that he is amongst the most dangerous animals to encounter on foot in Africa. Observing him from up close, this reputation does not seem to fit, but the silent and heavy-breathing mastodont turns into an aggressive killing machine when hunted down. Nunu is able to read the animal’s reactions and gives enough space to the large bull. I kneel and look up to the prehistoric animal barely 15 meters (45 feet) away from me. The rhino scuffs his feet and sprays large amounts of urine in a big cloud to mark his territory as part of his daily routine. Another way for them to deter competing bulls from entering their space is to step in their own dung and walk around to spread their scent. As white rhinos always keep their heads low by the ground, they pick up the border of a territory of another bull easily and stay away from it unless they think they can win the serious fight over it. Our rhino quietly moves on, feeding on the grass that he cuts with his wide flat lips, not minding our presence in the slightest way.

***

A few hours later, after having explored the bush, we are back in the game drive vehicle, fulfilled. At dusk, as we are driven back to the lodge for dinner, a greyish shape in the bush draws our attention. Luke stops the car and switches the engine off. As we realise this is another white rhino foraging, a high-pitched yelping sound breaks the chomping. Nunus eyes light up. “Do you know what this is?” he whispers. Puzzled, I am trying to recall which animals make this kind of sound. “Hyaena?”, I venture. At that moment the animal making the heart-breaking sound reveals itself: a tiny rhino calf is following its mother begging her for milk.

Tears run down my face. The rarity of such an encounter makes me realise that the future for this little one looks grim. Rhinos are slaughtered brutally for their horns: 70% of white rhinos have been killed in the last 10 years in South Africa. I can only hope that this cow and her calf will be spared here, in the last white rhino stronghold in the world where about 90% of white rhinos remain. At the current poaching rate, it is only a matter of time till they are massacred and their faces violently disfigured with machetes by poachers who are part of an organized international trafficking encompassing poor communities in Africa and the Chinese and Vietnamese black market, funding Islamic terrorism and corruption on the way.

Today’s approach to try and solve the problem is failing as overall poaching numbers only go up, and funding paramilitary groups to fight poaching only costs more and more. The failure of this repressive policy is confronting when facing a dehorned rhino, a practice that is becoming more and more common in private parks**. Nunu believes in education over law enforcement that has become an endless pit. “You protect what you love”, Nunu states. “95 percent of the children in the communities surrounding the park don’t even know what a rhino is…” he adds. “When food is scarce in their plates, how do you want them to care and stand up for any poached species?” Nunu is working with the safari industry such as Isibindi Rhino Ridge Safari Lodge to get school kids to experience the bush and wildlife, and start considering them as assets that should be conserved, instead of falling for the money they can make in poaching, a dangerous vicious circle which tends to start small and end big, with no coming back. Nunu knows the drill well… When he was a teenage boy, he found himself sneaking into a park with friends to poach for impalas. Luckily, he fell in love with these animals and turned his life around, getting involved in conservation in high school thanks to an environmental club. Nunu is not only literally very grounded as he has led us barefooted through the bush: he realizes that what these animals and communities need the most are solid business plans and entrepreneurship. Surrounding communities need to stand up against poaching (whether it is rhino horns or pangolins for China, vultures for traditional African medicine or cycads for the Middle East, to only name a few) and to do so they need to see a future with wildlife. A few years ago, after many trainings, internships, tracking and guiding jobs, Nunu created his luck: despite his poor upbringing, his love for wildlife and interest in finance allowed him to start his own company in collaboration with the Isibindi Rhino Ridge Safari Lodge, forming a path for himself and the trail guides he employs. His intention was clear: he spent too many years driving tourists in a 4×4 to tick the Big 5 boxes, and he wanted to make their safaris more meaningful by walking with them amongst wildlife, reconnecting with nature.

As we are seated on the viewing deck of the Rhino Ridge Safari Lodge for dinner, overlooking the hills where we walked, I reflect on this powerful and insightful experience. A blood moon rises on the Hluhluwe iMfolozi Park where legend conservationist Ian Player saved the Southern white rhino from extinction in the 1950’s. The Milky Way lights up the sky and reveals the natural skyline of soft hills and trees. I feel the warm breeze on my bare arms. The sounds of the bush resonate, as well as Nunu’s words: “Us, humans, we think we can fix everything, throwing money at our errors: buying carbon credits when we pollute the air, or filtering water when we can’t drink it anymore… When rhinos get extinct, no money will ever bring them back…” I am wondering if Ian Player’s success is not about turn into the biggest danger faced by rhinos, with our arrogant thinking that we can indeed fix everything with money… The bonfire crackles. My eyes follow a shooting star. I make a wish…

*Along wildlife trafficking, subsistence poaching is a reality in Africa. Snares are regularly installed in game parks, trapping any wildlife passing by and often let to die without even being recovered by the poachers. This zebra female was darted and freed from its snare as she was caring for her foal.

** Dehorning is a procedure that is used in some parks to protect rhinos from poachers. The animal is darted and the horns are sawed off under veterinary supervision. Studies show that the animal behaviour is hardly affected by missing its horn, however the intervention is risky and traumatizing for the rhino and the horn grows back. Poachers are ready to kill for only a few centimetres-worth making this very pricey surgery one that has to be repeated every two to three years.

Travel tips:

- The Rhino Ridge Safari Lodge is a private luxury safari lodge located in the 96,000-hectare Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, that hosts the largest population of white rhinos in the world. Beyond comfort and great service, guests enjoy daily sunrise and sunset game drives rich in wildlife.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles and photos (zoom out) about the area! Here is a short tutorial to download it.

For more wildlife inspiration in South Africa, click on the images below:

An amazing experience! Definitely something that’s on my list. And the Rhino Ridge Safari Lodge looks fantastic.

Oh, yes it is absolutely amazing. I hope you will be able to travel there soon. And yes, we tried them all, and we think the Rhino Ridge Safari Lodge is your best & most comfortable option to experience the beautiful Hluhluwe iMfolozi game reserve.

Claire

Wonderful post and stunning photos. I have great memories from this park. We stayed at the park run chalets, which were fine, but wow would I like to return and stay at that beautiful safari lodge. Thank you for sharing the good and the bad. I hope your wish comes true.

Thanks Caroline! We both love Hluhluwe iMfolozi and in this government-run park, they are doing a great job conserving the land. In terms of hospitality, private is indeed better at the moment & Isibindi is doing a great job. Happy we brought back these precious memories to you!

Claire

beautiful

Thank you!

welcome

What a lovely, detailed account of a very special trip. We, too, have seen white rhinos in South Africa, but poachers were ever-threatening. I was touched as you were by the photo of the baby and mother — I do wonder how long either or both will be spared from poachers. I have no idea how this will all end, but I feel as if we are losing the war against the marauders.

We are both happy you enjoyed this piece. We are at a point that every time we see a rhino, we feel extremely privileged. Now rhinos have become the symbol of poached species, and sadly many others are threatened. The COVID-19 crisis seems to have worsened the situation (less money from tourists for conservation, fewer people in the parks hence easier for poachers to go unnoticed, and tougher financial situation for local communities with an unemployment rate to the roof). We believe the solution is the development of the economy thanks to entrepreneurs like Nunu and businesses like Isibindi and we hope this article will give them more visibility and opportunities to continue their excellent job for the benefit of all.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts – very much appreciated as always.

Claire

One thing we were asked NOT to do: take photos and post on social media. The company didn’t want poachers to know that there were rhinos in their compound. It was the least I could do for them.

Ok. Many parks do not reveal how many rhinos they have, and some decide to sell them to decrease their security costs. Friends have just told us they saw 3 armed guards following a white rhino to protect it during their trip to Kruger. There are no photo restrictions in Hluhluwe that is well known for its rhino population & protection programs. What I really don’t get are the whatsapp sighting groups where people post photos and locations of wildlife live. I think these should be banned. Unfortunately, poaching is often an inside job, at least partially, and having just followed a tracking course (story coming up soon), it is not that difficult to track white rhinos…

It’s all so sad to me.