Article updated on February 4, 2026

Text: Claire Lessiau

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

I could hardly be farther from the haute couture stores of Avenue Montaigne or Rue Saint Honoré in Paris, the heart of fashion since the 16th century. Yet, here I am, my fingers gliding over the finest silk I have ever felt. The fabric is soft and delicate. The luxurious silk catches the light delicately, its depth enhanced by the intricate reliefs woven into its fibers. I am in rural Cambodia, just a stone’s throw from the temples of Angkor, where this rare Khmer silk is created—silk once reserved exclusively for the king.

“It took over a decade of research, trial and error, to revive the ancient silk-weaving techniques of the Khmers that had been forgotten,” says Sophea Pheach, the founder of Golden Silk. “And it all began with a sculpture of a devata from Angkor. Let me show you how…”

Pin it for later!

Unexpectedly, Sophea’s husband, Patrick, hands me a pair of 3D glasses. I put them on and gaze intently at a life-sized 3D image of a 12th-century Khmer sculpture from the temples of Angkor that has come to life. This devata is a sensual woman, dressed in fabrics of different textures, and more specifically, a piece of fabric draped around her hips that features a delicate relief.

“This is how we discovered that, during the golden age of Angkor, the Khmers had incredibly sophisticated weaving techniques to create the finest golden silk fabrics,” explains Patrick. As I hold a piece of silk in my hands, I notice it bears the same 3D texture. I am amazed.

“The little that had not been forgotten was destroyed and lost during the Khmer Rouge regime. A few local farmers managed to preserve some yellow silkworms. It took us ten years to unlock these techniques. We researched sculptures, examined ancient texts, interviewed weavers, and endured many failed attempts. Today, we employ over a hundred Cambodians, mostly women with no formal education. Some are from the Sovannophoum Komar orphanage I founded in 1992. They are all here, proudly making these fabrics and a living of their own”, Sophea explains, her voice humble yet filled with quiet pride.

Sophea has every reason to be proud. Nicknamed the “Mother Teresa of Cambodia” by the late King Sihanouk, she dedicated years of her life to working at the Site B refugee camp in Thailand, helping those who were less fortunate than herself during the Khmer Rouge regime. Her family had fled to France, where she received an excellent education. She was on the verge of marrying Patrick when she realized she had to return to Cambodia to aid those in need. What was meant to be a six-month stay in 1988 turned into a lifelong commitment. Today, she is still here in Cambodia, and Patrick, too, has made it his home.

After spending many years in refugee camps, Sophea realized that while providing aid was essential in the wake of such a devastating genocide, it was never a sustainable solution. Driven by a deep desire to restore the prestige of Khmer culture and, ultimately, empower the Cambodian people, she founded Golden Silk in 2002.

Outside the showroom, we stroll through a grove of mulberry trees with Patrick, feeling the heat of the dry season. “The life cycle of the yellow silkworms spans about a month and a half,” Patrick explains. “It all begins with the egg… or the butterfly…”

In a dedicated enclosure, long butterflies with short wings are kept. Their lifespan is only three days, and during this brief period, females lay an average of 150 eggs. These eggs are placed on newspaper for about 10 days, until they hatch into tiny caterpillars. The feeding process begins: the tiny larvae are fed four times a day, exclusively with mulberry leaves from the 12-hectare organic plantation. Over the course of 25 days, each silkworm consumes 4 kilograms (8lb) of leaves, multiplying its weight by an astounding 8,000 times! As the worms munch through the handpicked leaves that are evenly spread on them, their energy is stored up to create their precious, golden-colored cocoons they will enclose themselves into.

At first, the cocoon’s fibers are coarse, as the young worms learn to control the process. Then, about halfway, the silk becomes more uniform, producing the finest, highest quality golden silk. After about five days, most of the cocoons are collected for the silk production process, while a few are returned to the butterfly enclosure to start a new cycle. Males are longer than females, and this difference is visible in the cocoon stage: some male and female cocoons are selected for the breeding. The butterflies cut open the cocoons that can no longer be used for silk, mating within their one-day lifespan.

In a nutshell—or silk cocoon—, 1 ton (2,200lb) of leaves yields 60 kilograms (132lb) of cocoons, which are then processed into 5.8 kilograms (12.8lb) of raw silk. After washing, this results in approximately 4 kilograms (8.8lb) of degummed silk.

We step out of the worm station and into the spinning section, where three elegantly dressed young Cambodian women sit on low wooden stools. In front of them, steam rises from bubbling metal bowls, filling the air with a faint, indescribable scent. With steady hands, they carefully spin delicate threads of shiny silk from the boiled cocoons to kill the worm and make the silk fibers workable. As they gently rotate a wheel, they transfer the warm, wet strands of silk onto a frame.

The silk most commonly known in the West is white silk, produced from long, easily-spooled threads from large cocoons. In contrast, the Cambodian yellow silkworms produce smaller cocoons, requiring much more labor to extract the thread and yielding only about one-tenth the amount. The youngest woman pauses in her work, expertly separating the first half of the cocoon from the second half. She does this to ensure that the highest-quality silk is spun separately, highlighting the meticulous care taken in producing each thread.

Irregularities in the silk are carefully removed by hand, and the threads are sorted by size and color. Another young woman works with impressive speed and precision, her focus unwavering as she expertly sorts the strands. Once enough threads of the same size and color are gathered, the actual spinning process begins. Unlike white silk, this intricate process cannot be mechanized, requiring the skill and attention of these artisans to achieve the perfect consistency.

The threads are slightly twisted by hand to strengthen the fibers, then washed and hung to dry. As they dry, the silk threads take on a softer texture and a clearer, ivory hue. Only a trained eye can detect the subtle color variations, which are crucial for the dyeing process, ensuring the silk achieves its perfect shade.

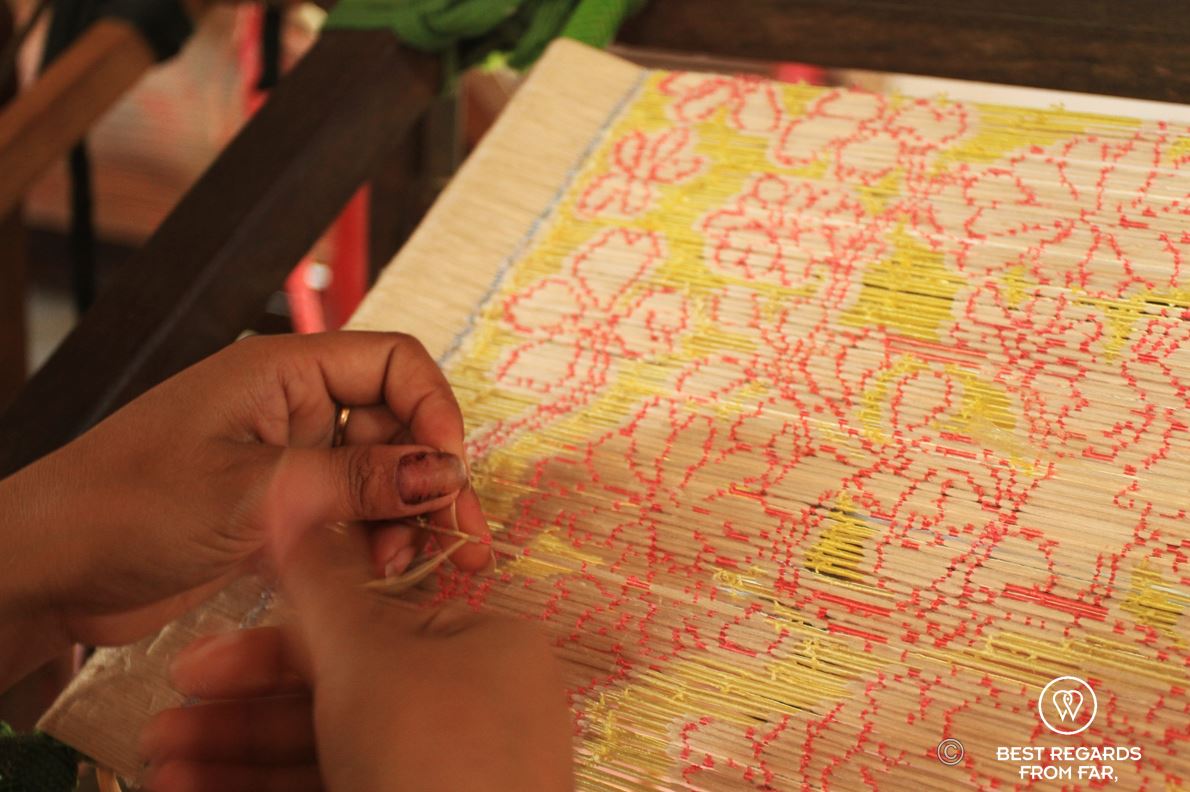

It is now time to select the pattern and the size of the fabric. In the next station, the silk is carefully arranged on a wooden frame, and the intricate design begins to take shape with colorful plastic wrappers. Patrick explains the process: “It is not uncommon to spend up to eight months wrapping the same piece. We use different colors of plastic, and once the wrapping is complete, the frame is soaked in a dye bath. To achieve the desired color on the silk, specific sections of the wrappers are untied, and the frame is dyed again. This process is repeated until the right colors are achieved, faithfully replicating the original pattern.”

Having participated to a dyeing workshop, surprised, I interject: “But the silk is not woven yet”. Patrick nods, and indeed, that is the next step. From the wooden frame, the thread is spun again and then brought to the loom. The loom is carefully set up to match the exact dimensions of the fabric, ensuring that the thread align perfectly, and the colors fall in place to form the chosen pattern. I cannot help but marvel at the precision and dedication required to achieve what connoisseurs call ikat.

I see the grin on Patrick’s face and sense he has something special to show us. As we head toward another workshop, he reminds us that 3D silk patterns were a lost art, and it was by studying the sculptures of the royal palace that Sophea decided to revive this unique craft in its original Cambodian style. In the next room, a team of three women is describing arabesques with their arms in fluid motions, guiding the setup of a special loom used for 3D weaving. Despite the cheerful atmosphere, their focus is intense. The process is incredibly delicate, requiring the utmost precision and discipline. I am in awe as I watch them work with the intricate network of horizontal and vertical threads, carefully adjusting each one to ensure it is perfectly aligned before the weaving begins.

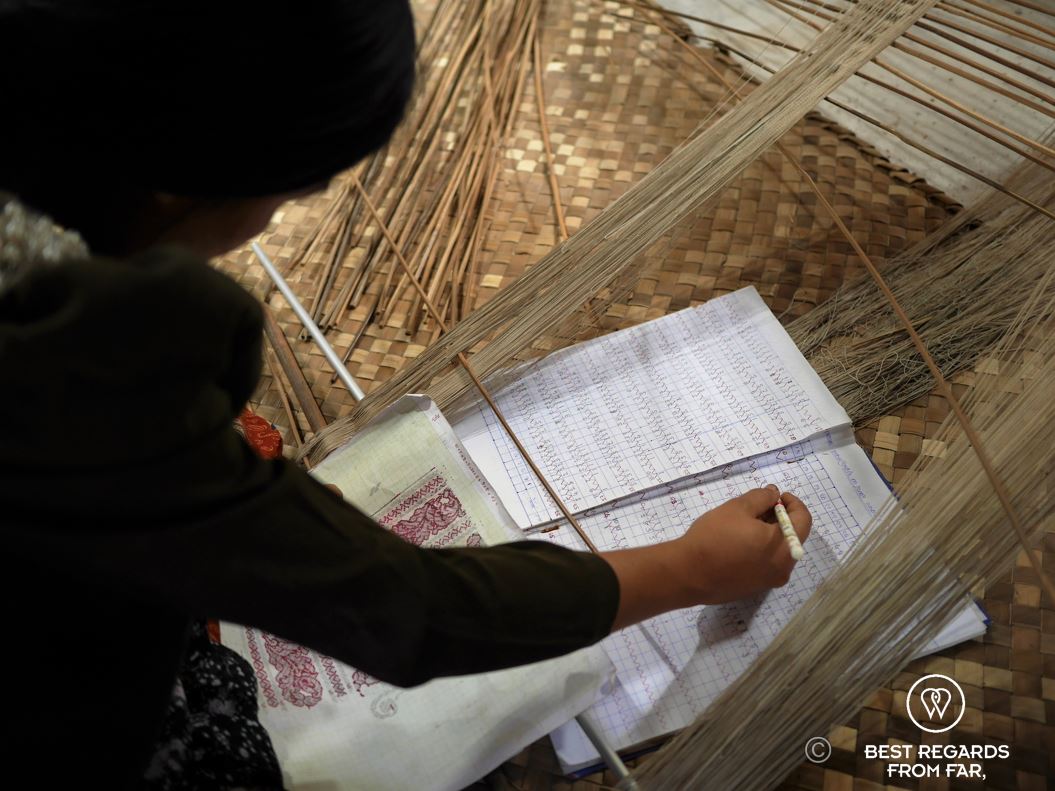

In the next room, like a wizard carefully noting down the recipe of her latest potion, an older woman scribbles indecipherable symbols in a notebook. This, Patrick explains, is the recipe for configuring the loom to create the specific 3D pattern. “In 2000, there were about 10,000 weavers in Cambodia. Today, only 300 remain,” Patrick shares. “Our goal is to preserve and develop this knowledge and revive these ancient techniques.”

Back in the showroom, I now see each piece in a new light. Their beauty and elegance remain unchanged, but with a deeper understanding of the process, I am struck by the dedication required to craft the finest silk of all—the rare Khmer golden silk—and transform it into exquisite scarves, shawls, throws, and royal brocatelle. Sophea Pheach has brought Khmer golden silk to life here, at the mulberry tree plantation and Preservation Centre of Golden Silk that is regularly visited by the crème de la crème of haute couture. In doing so, she has not only revived an ancient tradition but, more importantly, empowered the Cambodian communities she works with, providing them with both pride and meaningful employment.

Travel tips:

- To buy unique silk pieces from Golden Silk Pheach or inquire about visits, refer to their website.

- For more articles about the weaving traditions in Cambodia and Laos, refer to:

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles and photos (zoom out) about the area!

For more in Cambodia, click on the images below:

You might recall in one of your posts we commented about our journey to Siem Reap too. And where we visited a local artisan’s school too. Cannot recall where it was. Hopefully the younger generations will keep this tradition!

Given the amount of effort to get there, I trust Sophea to pass it on, and I’m sure the know-how is documented!

absolutely loved your blog. Traditional weaving is facing similar decay even in Indian rural sectors too. Such a rich history of techniques this industry has. I bought few meters of silk fabric while traveling in Vietnam. They claimed it to be from the soil of Cambodia. what fine finesse! But then, silk everywhere is a sign of luxury. 🙂

Thanks for the compliment! It is beautiful to see these ancient techniques being revived and passed on, indeed.

Amazing process and excellent craftmanship.

Thanks for your read & comment!

☺👍