Text: Claire Lessiau

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

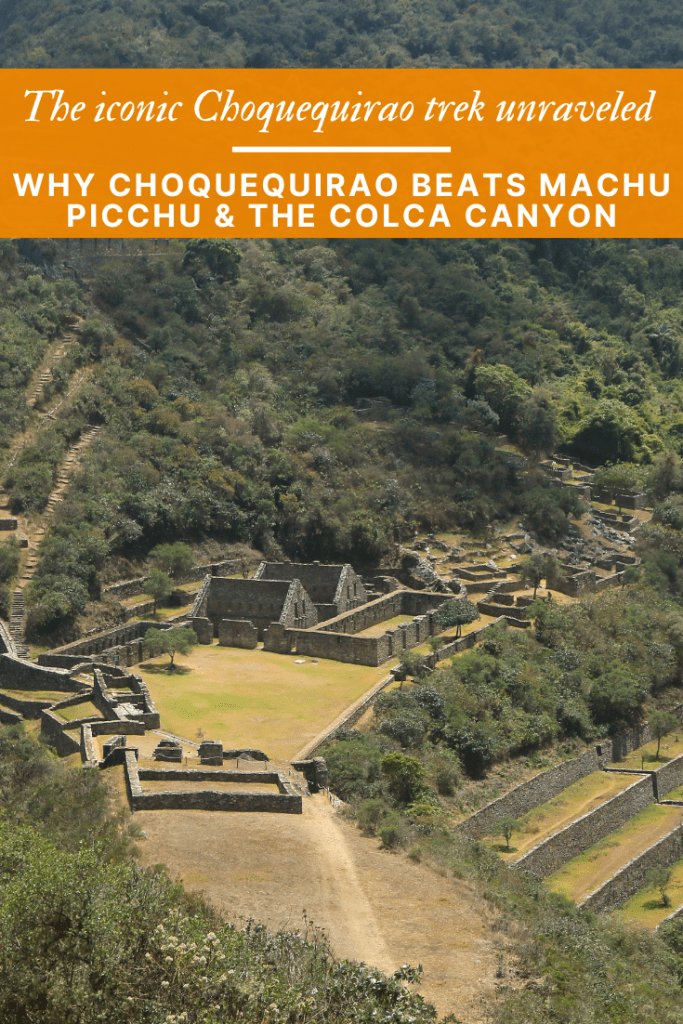

One of the most remote archeological sites in Peru, Choquequirao—often considered the “little sister” of Machu Picchu despite its larger size— is not for the faint of heart. To this day, it can only be reached via a strenuous and magnificent trek that surpasses the popular Colca Canyon in every way. For the few brave and adventurous travelers, the UNESCO World Heritage site of Choquequirao, the Inca city, awaits…

Pin it for later!

After a scenic four-hour drive from Cusco, the small village of Cachora eventually appears at the end of the road, with the snowcapped peak of Kiswar in the distance. Peaceful Cachora serves as the starting point for one of Peru’s most beautiful treks, leading to the Choquequirao archaeological site. From there, the trail continues towards Machu Picchu—or for the most daring hikers, to Vilcabamba, the last capital of the Incas, requiring an additional week of hiking along the Inca Trail.

Created by the Spaniards as part of their reduction policy, which aimed to relocate indigenous people into cities for the purpose of evangelizing and “civilizing” them as they saw it—while also making them easier to control—Cachora has remained a small settlement with a handful of accommodation options for adventurous travelers. As we approach La Casa de Salcantay, its owner Yovana, steps out and warmly greets us with a genuine hug. While for many, Choquequirao is a once in-a-lifetime adventure, for us, it will be our third expedition to this captivating site, our favorite in Peru. At the far end of Cachora, the view from La Casa de Salcantay guesthouse over the Vilcabamba mountain range is simply unbeatable. From Yovana’s flowery garden, I am in awe. In the foreground, some locals are plowing their fields before the start of the first rains. In the distance, the snow-capped Kiswar Peak culminates at almost 6,000 meters (19,685ft).

The relatively flat dirt road at the foot of La Casa del Salcantay leads to Capulyioc, about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) further. This is where most hikers begin their trek, after a break at the viewpoint. In the early morning and evening, scanning the sky for condors and the nearby rocks for nesting sites can be rewarding. These majestic South American giants often glide on the thermal winds above the Apurímac Canyon, 1,700 vertical meters (5,000ft) below, and our midpoint for the day.

As the Apurimac River glitters in the sun like a long and shiny snake winding its way all the way down, the “great speaker” (as it translates in Quechua) is a roaring river that we need to cross before ascending the opposite bank. For now, ignorance is a bliss: our eyes follow a rather broad and dusty trail well cut through an arid landscape of yellow grass, gently leading down. As we begin our descent, it does not take long for our mules and horses, led by our arriero, to pass us by. Their footing is sure, having navigated this trail countless times before.

The challenge of this trek is, of course, the elevation that can be brutal on the knees on the way down and taxing on the heart on the way up, but more importantly, it is the heat. With hardly any shade on the way down, and despite the altitude not being particularly high for Peru, staying hydrated properly is crucial. Thankfully, the oasis of Chiquisca offers welcome shade that makes it the perfect location to take a break—and even better for a homemade lunch and some refreshing drinks. A bright yellow Inca Cola has never tasted that good!

About an hour further down, we eventually cross the Apurimac River on a suspension bridge. The water looks inviting under the midday sun, at our lowest and warmest point of the trek. We know what lies ahead—or at least a part of it: from our arid trail on the left bank of the Apurimac, we could clearly see a steep section of the 12-mile-zigzag path leading to Choquequirao. In the early 1900s, an expedition led by Núñez, the prefect of the Province of Apurímac, set out on a treasure hunt. His team built a bridge and spent three months laboriously cutting a path leading to the archeological site. Despite their best efforts, they left empty-handed, having made no dramatic discoveries.

As the trail gains altitude along the right bank of the Apurímac River, wild orchids begin to appear and more greenery announces the lush, dark green vegetation higher up. Despite the heat, we are making good progress, riding our horses on the challenging and rocky terrain. We pass Santa Rosa and continue to Marampata, by far the best place to spend the night. This settlement, accessible only on foot, has grown significantly in the past 15 years since my first visit. Today, it offers several basic accommodation options, though none compares to the welcoming Refugio Choquequirao. Thankfully, it is the very first stop upon entering Marampata, where we are warmly greeted by its owner, Elisabeth. The view is, once again, absolutely breathtaking—literally after a full day of trekking and riding! While taking in the view, we spot, far in the distance, the majestic Choquequirao perched on the saddle of a spur projecting some 1,700 meters (5,000ft) above the deep Apurímac Canyon!

Choquequirao shares many similarities with Machu Picchu: its remoteness, dramatic location, and its liminality between the highlands and the jungle. “The Cradle of Gold” in Quechua is far larger than Peru’s most famous Inca archeological site, with only a third explored so far. The view from the ruin can hardly be described—perhaps even more breathtaking from the 3,272-meter-high mountain pass (10,897 feet) above, along the Inca Trail. From there, the trail plunges on the other side of the mountain toward Yanama, leading to either Vilcabamba or Machu Picchu, passing abandoned silver mines that likely once supported the noble houses of Choquequirao.

From the pass, the Usnu—the ceremonial platform of Choquequirao—lies in the foreground, while the mighty Apurimac River winds far below like a tiny silver ribbon towered by layers upon layers of majestic mountains. Above the ruins, a dazzling snowcapped peak fades into the clouds that provide the humidity for the lush surrounding vegetation. Combined with this humidity, the winds created by the temperature difference between the warm Apurimac riverbed and the cold snowy summits create a diverse range of conditions for farming a variety of crops. The vast extent of the terraces—only a small section has been excavated—gives an idea of the importance of this site, as well as the advanced farming and engineering skills of the Incas.

If some think that Choquequirao was less important than Machu Picchu for the lack of polygonal walls or big granite boulders, they forget that the Incas built mostly with stones from nearby quarries, and free standing stones are not found here. Instead, the rough, coursed ashlar walls were plastered with clay both inside and out and painted a soft orange color. The houses are large, rectangular structures made of fieldstone set in clay, showcasing late Inca craftsmanship: trapezoidal doors and niches, bosses and rings designed to hold down the thatch, steeply pitched roofs, and an upper half-story beneath the eaves, accessible by lines of steps projecting from the end walls.

The ancient irrigation system connects the liturgical upper area, or Hanan, with its great staircase, fountains, buildings, and squares to the lower area, or Hurin, where buildings and royal residences are arranged around a pentagonal square. This square is dominated by the truncated hill, which was intentionally shaped to host the ceremonial platform or Usnu.

After the first Inca emperor, Pachacutec, defeated the belligerent Chancas who once dominated the Apurimac region—an event that sparked the Inca expansion and the rise of the Inca Empire—it is believed that he sought to impress this powerful tribe by constructing a strategic control point between the Andes and the Amazon regions. Like all Inca cities, Choquequirao would have also served as a religious center. Recent archaeological research suggests that Choquequirao was developed as a royal estate during the late 15th century by Pachacutec’s son and successor, Topa Inca. Inspired by the grandeur of his father’s mountain estate, Machu Picchu, Topa Inca may have felt compelled to create a site of equal grandeur.

Before the arrival of the Conquistadors, the Chachapoyas in northern Peru were conquered by the last undisputed Inca emperor, Huayna Capac, and these skilled builders were sent to Choquequirao. As part of the Inca strategy to weaken resistant tribes by dispersing their populations through forced relocations, it was no coincidence that the Chachapoyas were brought to this specific area. The cloud forest ecosystem surrounding Choquequirao is reminiscent of the Chachapoyas’ homeland, and it is likely that the Incas leveraged their agricultural expertise. Above the Terraces of the Llamas, where white quartzite camelids decorate the agricultural levels, the uppermost wall features a distinctive white inlaid zigzag pattern in the unique Chachapoyas style—a design not seen in any other Inca constructions.

The majestic and elusive Choquequirao, located on the way to the last capital of the Incas in the jungles of Vilcabamba, was abandoned at some point in the late 16th century, likely around the fall of the last Incas in 1572. Since then, only a few intrepid explorers have ventured to this site. The first reported visit to Choquequirao was in 1710 by prospector Juan Arias Díaz Topete. Over the next century, several others, including French explorer Eugène de Sartiges, reached the site. Choquequirao also gave Hiram Bingham his first taste of lost Inca cities and sparked his fascination with the mysteries of Vilcabamba, eventually leading to his discovery of Machu Picchu. Bingham explored the site in 1909, spending several days sketching, photographing, and mapping the ruins. After that, Choquequirao was largely forgotten until the Peruvian government showed interest in the late 1980s. Today, a busy day at the mysterious ruin sees no more than a dozen visitors, and fortunately, today is not even a busy day!

***

After the magical yet exhausting visit of the archeological site of Choquequirao, most travelers return the same way to Cachora. The view from the mirador at Capulyoc takes a new dimension, with a deeper sense of perspective. For us, it brings a wave of nostalgia and a bittersweet taste of adios.

A few continue on. The adventure along the Inca trail passes by more ruins. After crossing the Rio Blanco a bit upstream from its confluence with the Apurimac River, the hike up leads to a couple of very simple houses. In the early 2000s, two families moved from Yanama to this area in search of more land for farming and pasture. The Perez family, who offers a very basic room with a few beds, is one of these. Guinea-pigs run around, nibbling up every scrap that falls onto the earthen kitchen floor. Soil still clings to the boiled potatoes that are part of every meal. Dinner is running around outside, between the kitchen and the main house—perhaps a chicken or a pig, reserved for very special occasions.

From there, a trail leads to Qoriwayrachina, an Inca settlement discovered only in 2001, which I had read about in National Geographic before departing. In his article “Mystery mountain of the Inca” (February 2004, National Geographic), author and archeologist Peter Frost describes the discovery of the ruins, from which decorated Inca pottery were unearthed and burials were found. Further ahead, the hostile 4,200-meter high (13,780 ft) San Juan Pass to Yanama leads to the lost settlement, connected to civilization by a daily colectivo, which one expects in the cold, dark night—or perhaps instead continues farther on to Machu Picchu or Vilcabamba… Treasures and adventures still await in this remote corner of Peru.

Travel tips:

- What makes Choquequirao truly special is that it is hardly visited, a stark contrast to the over tourism issues that Machu Picchu faces in its effort to not lose its UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

- Go soon though as a cable car project has been approved and if it is still years away at the time of writing, it will completely change the experience.

- For an excellent and ethical agency setting up guided Choquequirao adventures from Cusco, contact Escapate Peru.

- Food and drinks can be purchased along the way to the ruins. If continuing toward Yanama, be prepared with extras, as there is nothing between Choquequirao and Yanama (unless the Pérez family is around). Very basic accommodation are available. A tent is essential for the stretch between Choquequirao and Yanama, as it is too long to make without a bivouac. The best accommodation options are:

- Refugio Choquequirao (WhatsApp in Spanish: +51 966 282 903)

- Family Perez

- Yanama: Camping Las Flores y hospedaje

- Mules and/or horses can be rented with their handler (arriero) in Cachora. The mules carry the load, leaving hikers with only their daypacks, and they can also be ridden instead of hiking up. The best contact is Señora Doriz on the main square. La Case de Salcantay can help you arrange for it.

- Check out this interactive map (quick tutorial) for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

For more in Peru, click on these images:

I did this!!!!Sent from my iPhone