Text: Marcella van Alphen & Claire Lessiau

Photographs: Claire Lessiau

Founded in 1572 by the Spaniards, under the orders of the conquistador Andrés Díaz Venero de Leiva, the Colombian town of Villa de Leyva, with its cobbled lanes, whitewashed houses topped with terracotta roofs, and bright fuchsia bougainvillea climbing their walls draws visitors from all over the country and beyond. This slow-paced colonial village invites you to wander and explore beyond its photogenic façades. Beyond the charm lies something more: scenic trails, caves, rich historic sites—and for the sporty ones, a vantage point above town offering sweeping views over the Eastern Andes.

Pin it for later!

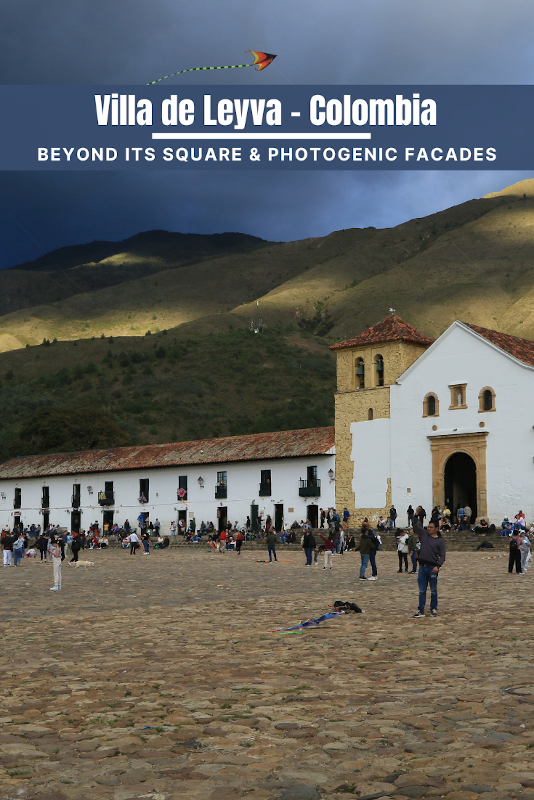

Plaza Mayor: Colombia’s Largest Cobblestoned Square

At the heart of Villa de Leyva lies the popular Plaza Mayor. With its gigantic 120-meter by 120-meter (394ft by 394ft) dimensions, it is the largest cobblestoned square in Colombia and one of the largest in South America. Around the square, the city hall and colonial-era buildings serve as a foreground to the dramatic Eastern Andean mountain range, with to its east the parish church of Nuestra Señora del Rosario. Specialty coffee shops, quirky boutiques, and a wide variety of restaurants line the square and surrounding streets.

While the colonial armies of the Spanish crown that once were formed here on the square to receive their orders have long gone, locals flock together to fly their kites on weekends and purchase ice creams from mobile vendors while enjoying the views.

The well-preserved colonial architecture came at a price: Villa de Leyva boomed as the main center of production of wheat, but in 1691, an illness affected the wheat and the city fell into lethargy, becoming a resting village. Today, the quiet 18,000-inhabitant parish is on the list to tentatively become a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and falls out of its lethargy, especially on weekends.

Cueva de la Fábrica: Descending into a Sacred Cave

A short scenic ride takes us through the surprisingly semi-arid Saquencipá Valley and a dirt road winds over rolling hills to a secluded house with expansive views on surprisingly green slopes in this climate. We greet our young guide, Nicolás Peña Fajardo, who is about to take us to explore the Cueva de la Fábrica.

This cave was once sacred to the Muisca people, an advanced civilization that flourished between 600AD till the arrival of the Spaniards in the 16th century. We are in the heart of their territory and according to the local legend, the goddess Bachué, mother of all human beings who was born in the nearby Lake Iguaque, was venerated in this cave.

We hike down from around 2,200 meters (7,218 ft) of altitude and the cool air is a pleasant contrast to the dry valley floor below. Along the way Nicolás points out succulents and fique plants which fibers once clothed the Muisca. Indigenous to the Andes Mountains, and related to agave but with bigger leaves, fique leaves are used these days to make environment-friendly coffee bags, or high-quality craft paper. 143 million-year-old marine fossils surface from the clay soil in which various wild orchids thrive and add color to our walk.

At the circular cave entrance, we gear up to the clinging of carabiners to rappel down the natural cave. I recall my intensive training to rappel down the much deeper 7th Hole in Oman before lowering myself for this free rappel. Shortly after, my feet touch the ground in the “Gallery of the Sun”, a chamber that was used as a time-keeping device by the Muisca who had outstanding knowledge of astronomy. We venture deeper into the cave where we still see the marks of the gradual retraction of the sea that was present over 110 million a years ago.

Deeper still and only lit by our headlamps, we enter galleries where bats roost. Right when I think it is getting quite dark, I start feeling the lack of oxygen and a strong smell of ammonia caused by the bat excrements. Nicolás pauses and explains that we have arrived in the very cave in which the chosen Muisca man had to spend nine years in isolation before making offerings in Lake Guatavita to appease the gods. During this ceremony, covered in gold powder, he would sail on a raft onto the lake. Witnessed by the conquistadors, this led to the legend of El Dorado: the Spaniards thinking that if gold could be spared this way, the natives must have vast quantities of it hidden somewhere…

Just like the Spaniards searched for gold, I am eager to find the exit of the cave. Nine years… While my eyes adjust to the daylight when I step out, I gratefully embrace the warmth of the sun on my skin, the fresh air, the smell of flowers, and the sounds of the birds, and spare a little thought for the men who had to spend almost a decade in darkness.

The Christ Statue: A Rewarding Short Hike

Back in Villa de Leyva, and craving sunlight after our descent underground, we set out for a short hike as one of the most rewarding trails around Villa de Leyva begins just in the heart of town. Shortly after passing the Plaza Mayor, a dirt trail winds out of town, climbing steadily through dense forest. Branches arch overhead and the forest floor is humid with moss. After about half an hour, we break above the tree line into paramo grasslands where we climb up a long slippery rock slab.

Continuing upward, the trail curves and steepens until we reach the large statue of Cristo Rey de Villa de Leyva, perched on a hill overlooking the town and valley. The viewpoint —listed as “Mirador El Santo Sagrado Corazón de Jesús” on our 3D map— offers sweeping views over the colonial town’s tiled roofs, the river valley, and the Eastern Range of the Northern Andes. The rare and precious ecosystem known as Paramo of Iguaque serves as an important water resource and starts just behind the Christ statue. Its access is forbidden and while threatening storm clouds pack up on the horizon, we zip down the same way back!

The House of Antonio Nariño

We are heading back into town, following the path of El Libertador, Simon Bolivar, who has left a decisive mark on Colombia as well as many other South American countries, Bolivia being even named after him. The cobblestoned street leads us to the house of another freedom fighter: Antonio Nariño (1765-1823).

Nariño was a man of many talents: a journalist, businessman, botanist, intellectual, humanist, and passionate about medicine, agriculture, scientific innovation, and politics. He played a major role in shaping the independence movement of Colombia. He was the first translator of the “Rights of Man and of the Citizen”, also known today at the “Declaration of Human and Civic Rights” from French to Spanish in America. Issued by the National Assembly after the French Revolution, the text is a plea for freedom, equality, and independence and today still the founding principle of the French Republic (and had important intellectual and ideological influences on the USA amongst other countries). Seen as a rebellion against the colonial rule of the time, Nariño was sentenced to exile in Africa, and suffered the confiscation of all his assets, and the loss of his privileges. Overall, he spent 21 years of his 58 years in prison.

Antonio died in this 16th century colonial house in Villa de Leyva on December 13, 1823 of tuberculosis, three months after settling here from Bogota, hoping the semi-arid climate would do him good. The typical Andalusian-style house, built around a patio with a fountain in the center and a garden in the back, offers a glimpse into the life of Antonio Nariño.

***

Whether you are a history buff, adventurous traveler, or simply want to slow down to take in one of the most beautiful villages of Colombia, Villa de Leyva is one of these places that offers something for everyone. Already a favorite for Colombians, it is fast becoming a must-visit for the ones in the know…

Travel tips:

- For a comfortable stay, book the Hotel Boutique & Spa VDL Colonial that offers spacious rooms in a colonial building with a spa and relaxing massages.

- To explore Cueva de la Fabrica, make sure to book ahead and plan for half a day.

- The house of Antonio Nariño is a small but interesting museum to stop by, please refer to our map for its location.

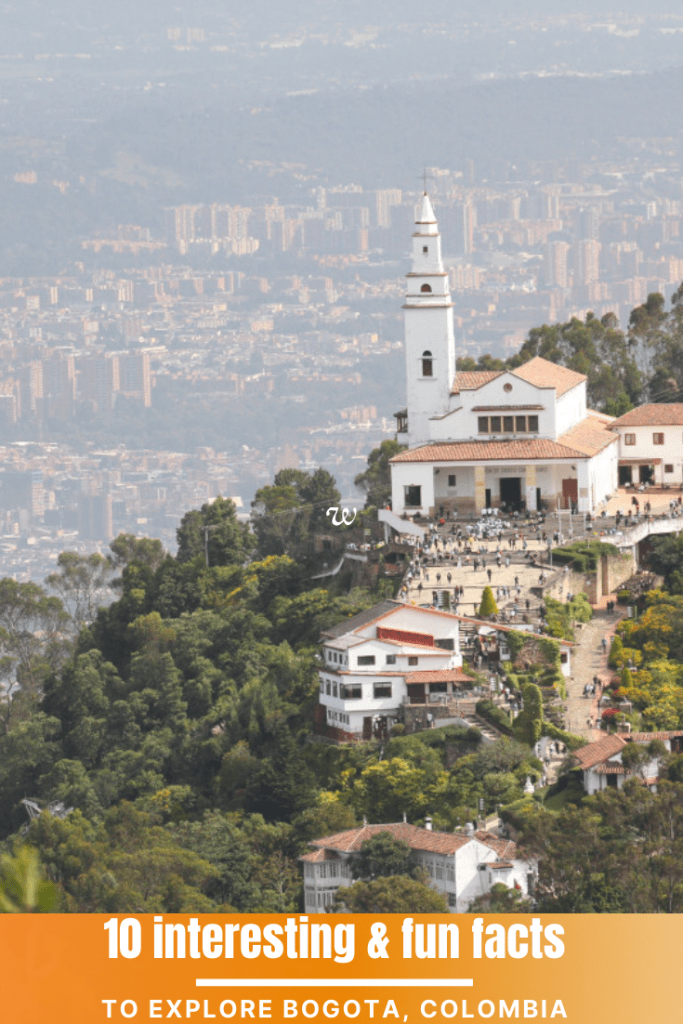

- The Museo de Oro in Bogota showcases a golden raft depicting the offering scene described in this article and is one of the masterpieces of the Muisca people.

- To enjoy Villa de Leyva the best, we recommend avoiding weekends.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

For more in Colombia, click on these images:

What a wonderful place, a bit of everything. I’m sure a spa session was very welcome by the end of the day!

Yes, whichever day, it always works 😉 But I must admit that given all the activities, it was perfect. Thanks for your read & comment. Best, Claire

Hi Girls,

Sounds beautiful! You are lucky that you are far away from Mpumalanga, we are having the worst weather I can recall, anywhere!!

On Dec 27 we were hit by a Tornado, with no warnings whatsoever, and since then its just wet,wet,wet, and more to come.

Kruger Park is flooded, and many parts are closed!!

Take Care

Chris Colverd x

Hi Chris, yes, we have been following the news. It sounds really crazy. I hope your property has not been damaged. Stay dry!! Take good care.