Article updated on May 24, 2025

Text: Claire Lessiau

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

Discover the White City of Arequipa, from its colonial cultural sites, to its gastronomic restaurants, adventurous treks (careful, not for the faint of heart!), and most famous resident—Juanita:

- The food scene in Peru’s gastronomic capital [more specifically: Clandestino]

- Peru’s 2nd largest city is the most or the 2nd most beautiful of Peru!

- Saint Catherine’s Monastery: a colorful citadel of sillar in the White City

- Trekking the deep Colca Canyon [world’s second deepest!]

- Misti Volcano (5,822m; 19,101ft): Conquering New Heights

- Meet Juanita, The Ice Maiden of the Andes at the Museum Santuarios Andinos

Pin it for later!

#1-The food scene in Peru’s gastronomic capital [more specifically: Clandestino]

Young Peruvian Chef Mauricio Mello takes you on a carefully crafted gastronomic expedition through the diverse ecosystems of Peru, where he unearthed forgotten recipes and rare ingredients that form the soul of the country. After working with renowned chefs worldwide, including Virgilio Martinez Véliz of Central in Lima (world’s best restaurant per The World’s 50 Best Restaurant list at the time of writing) his explorations of his own country have led him to learn recipes from humble family cooks to Peru’s award-winning baker. Before establishing Clandestino in the gastronomic capital of Peru, Chef Mauricio spent seven years reviving and reinterpreting recipes lost to revolutions, earthquakes, wars, and epidemics.

The perfectly balanced 10-course tasting menu is a masterpiece of unique flavors, textures and nuances taking you to the roots of Peru where each dish tells a very specific story of the country’s rich history and diverse cultures. Superfood and rarely used ingredients such as liccha, or the leaf of the quinoa plant, accompany local meat and fish plated in an original and earthy way to create a complete experience that the mixologist complements with original cocktails perfectly paired with the dishes.

Embark on this fine-dining culinary journey like no other at Clandestino Restaurant in Arequipa!

Travel tips:

- Make sure to book ahead of time: Clandestino restaurant.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

#2-Peru’s 2nd largest city is the most or the 2nd most beautiful of Peru!

It is a close call between the colonial Arequipa and Cusco, the former imperial city of the Incas. Yet, both cities are completely different.

Founded in 1540 by Don Garcia Manuel de Carbajal, Arequipa is nicknamed “The White City,” after the distinctive sillar, a type of white volcanic stone erupted by the surrounding volcanoes. The volcanic stone, a variety of rhyolite unique to Arequipa is formed by the accumulation of ash and volcanic elements during eruptions of the Chachani (6057m; 19,872ft), Misti (5822m; 19,101ft) and Picchu Picchu (5,664m; 18,582ft) volcanoes guarding the city and forming a phenomenal backdrop.

If its lightweight and porosity had made sillar an easy-to-work material ideal for ornamental purposes, it evolved into a proper construction material after many earthquakes destroyed the city over and over again. Since the end of the 16th century, local architects were able to build walls, arches and domes, which survived the local seismic activity.

The city’s historic center beauty lies in the blend of this white volcanic stone and refined baroque and neoclassical architecture, making it a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Flourishing during the 17th to 19th centuries, Arequipa’s prosperity was fueled by the silver trade from the very rich Potosi mine in Bolivia and the alpaca wool trade. This affluence manifested in churches, casonas (mansions), and convents, including the iconic Santa Catalina, all built with sillar.

#3-Saint Catherine’s Monastery: a colorful citadel of sillar in the White City

Built almost entirely with sillar, the Saint Catherine’s Monastery stands as a timeless citadel in the heart of Arequipa, telling quiet tales of seismic resilience, centuries of isolation, and a commitment to spiritual devotion.

Dating back to the 16th century, the seismic rhythm of the region has led to continual additions, reconstructions, and modifications of the monastery. Native and European techniques have seamlessly fused with the peculiarities of sillar, shaping the monastery with archways, vaults, domes, buttresses, vibrant patios, painted in a vivid chromatic palette of natural pigments.

Step into the locutorio, a room where cloistered nuns could receive visitors, always in the company of a “listener” nun. The subdued yellow light, filtering through skylights, paints a serene ambiance. A gateway to the outside world, wooden grids prevented physical contact between the nuns and their visitors, reflecting a life dedicated to prayer and contemplation in isolation.

For 391 years, until 1970, the monastery had remained isolated, as a sanctuary for women of diverse social backgrounds who embraced the veil or sought refuge – living in an isolated part – in times of war or rebellion.

Handicrafts, created in silence to attain spiritual peace, were part of the nuns’ daily lives and still are. Intricately embroidered garments for religious figures and delicate robes for the Baby Jesus and the Virgin Mary were meticulously crafted within the monastery’s walls. Today, cookies and local specialties homemade by the nuns still provide an income to the convent.

The monastery’s cells, where nuns would spend the rest of their lives, were financed by families according to their financial means. If some are grander than others with a patio and a kitchen with masonry ovens, each cell hosts a niche to hold an image of the Virgin or of a saint for special devotion, and a sleeping platform under a semicircular arch, intended to provide safety in the event of an earthquake.

The vibrant indigo blue Orange Tree Cloister contrasts greatly with the six intense ochre streets within the citadel, revealing rows of quaint houses hosting cells. Among them, the Zurbaran room, or infirmary, sheltered the sick nuns. Treated only with the ointments and natural medicines prepared by themselves onsite: no doctors would be allowed in except in cases of life-threatening illnesses, and always under the supervision of a nun.

As a few nuns are crossing the main cloister briskly to be on time for mass, visitors of the timeless citadel within the city are reminded of the modern world, hushed by the thick sillar walls and awaiting just a gate away.

#4-Trekking the deep Colca Canyon [world’s second deepest!]

The Colca Canyon regularly makes it to the top of Peru’s best treks with its awe-inspiring landscapes.

Indeed, accessing the canyon from Arequipa, panoramic vistas of century-old terraced fields towered by snow-capped peaks, quaint villages, and colossal cliffs that plunge dramatically into the abyss of the canyon are breathtaking – or maybe this is just our bodies reacting to the altitude of the Mirador de Patapampa at 4,800m (15,750ft)! Nestled in the Andes, Colca is one of the world’s deepest canyons, almost twice as deep as the Grand Canyon in the United States (1,829m; 6,000ft at the deepest).

Luckily, the trail leading us to the Oasis of Sangalle at the bottom of the canyon does not go anywhere near the deepest point in Huambo where the gorge cuts as deep into the rocks as 3,534m (13,648ft). Still, a drop of 1,690m (5,550ft) followed by 1,190m (3,900ft) of positive elevation to conquer require stamina, and a night in the canyon – or for some the help of a resilient mule to go back up!

Surrounded by lush greenery and palm trees, Sangalle Oasis provides a surreal contrast to the arid landscape above. Rustic lodges with pools fed by nearby springs offer an unexpectedly comfortable rest in the greenery in the midst of the rugged terrain that divides the trek in half.

An early departure before sunrise to beat the heat of the day, allows trekkers to complete the hike and enjoy Cruz del Condor on their way back to Arequipa. There, the world’s largest flying birds, the magnificent Andean condors soar gracefully over the canyon’s majestic and rugged landscape that has been explored in depth (pun intended) during a 2-day trek.

Travel tips:

- All the trekking stats can be found in this interactive map below.

- Many agencies can set up the trek in Arequipa that is very popular with backpackers. The recommended agency run by an official mountain guide is Quechua Explorer.

- For avid hikers, the Choquequirao trek is more challenging, quieter, and leads to an exceptional archeological site!

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

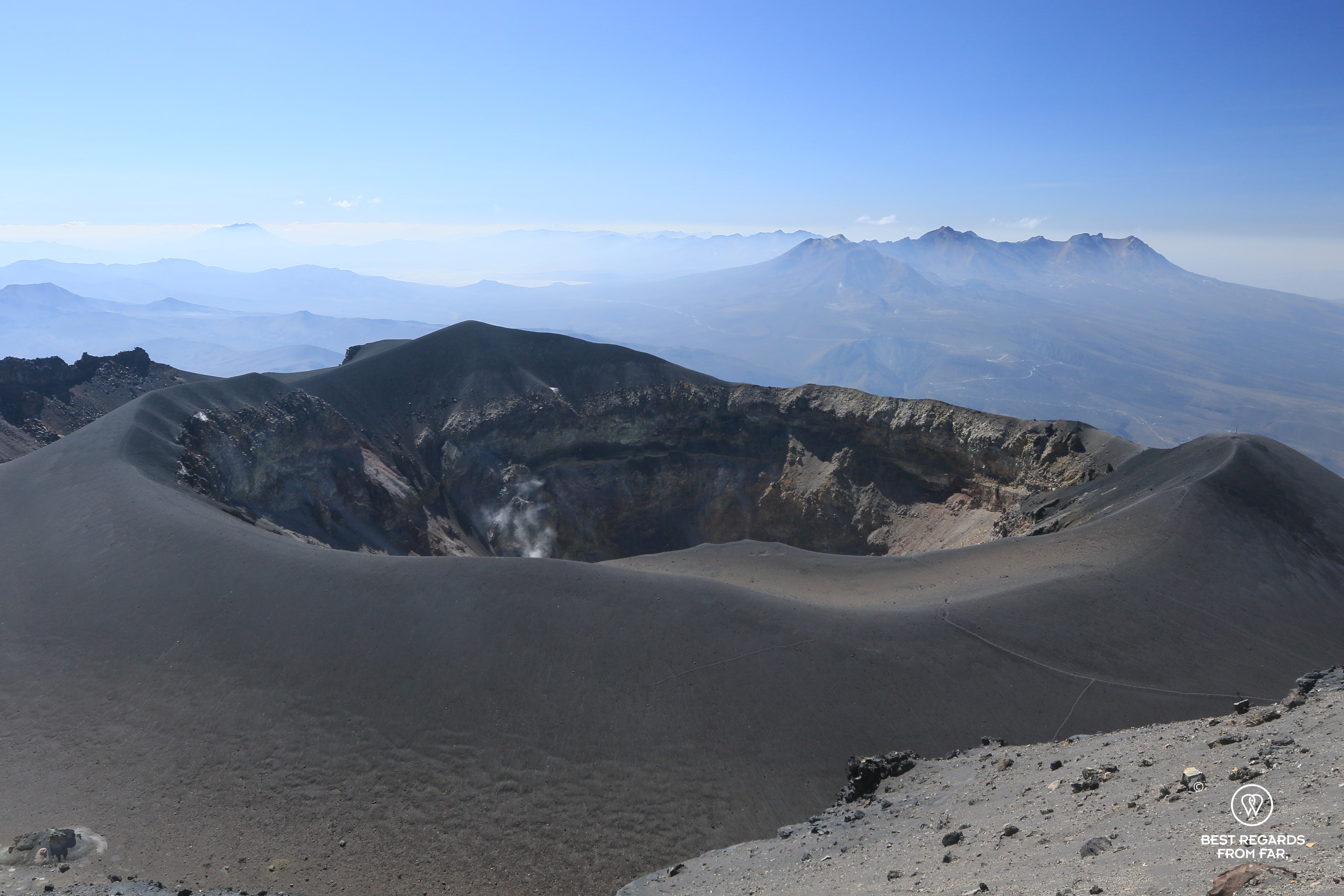

#5-Misti Volcano (5,822m; 19,101ft): conquering new heights

Perched in the southern Andes of Peru, the majestic Misti Volcano stands as one of the three sentinels of Arequipa, tempting trekkers to reach new heights, attempting to summit its 5,822 meters (19,101 feet) above sea level. Not the highest (this would be the Chachani Volcano (6057m; 19,872ft)), Misti is the most challenging peak around Arequipa with a positive elevation of 1,784 meters to conquer.

A good acclimation is essential to not have to abort due to altitude sickness, and 2,335-meter-high (7,660ft) Arequipa is the perfect base for it. The challenges of high altitude, strong winds, and cold temperatures call for a competent professional guide. Many agencies in Arequipa thrive on much easier hikes such as the popular Colca Canyon, and not all have the seriousness and qualification to set up such an expedition. Among the ones that do, many propose to ascend via the cold and regularly snow-covered South face, as it eases their logistics from Arequipa. Instead, starting the trek North-East of Misti eliminates the uncertainty of snow and ice for a safer undertaking. It only requires a longer drive with a 4×4 through surreal volcanic landscapes of the Salinas y Aguada Blanca Nature Reserve.

Vicuñas freeze as the off-road vehicle approaches on the dirt track, and the volcanic peak looms ever larger.

The first day is a short 500-meter-climb (1,640ft) to reach the base camp. Given the weight carried between the sleeping gear, warm layers and above all water, it is a significant milestone. As the sun is still high in the sky, trekkers set up camp on Misti’s treeless slope, sheltering the tents from the wind that is bound to pick up overnight. As soon as the sun dips below the horizon, the temperature drops fast. Dinner is not a social undertaking and is very quickly eaten, or at least as quickly as allowed wearing thick gloves. The headlights are off early as the alarm is set for 2a.m…

The final push to the summit is a long one! Starting in the pitch dark night with a few bright stars lighting up the sky, trekkers begin the final ascent in the early morning hours, guided by the white glow of their LED headlamps.

Dawn on Misti is a spectacle reserved for the intrepid few who overnight on it. The journey is extremely challenging on a granular terrain on which every step up feels like taking two down. Both physical endurance and mental resilience are tested to the limits. Just one step in front of the other… With each step, the reward grows nearer, as the sun bathes the volcanic slopes in hues of pink and lights up the Chachani Volcano in the distance. The warmth expected from the sunrays is annihilated by the cold air blown on us faster and faster by the unforgiving wind as we gain altitude. The very last hairpins are mind-blowing (pun intended) with a felt temperature of -13°C that specific day, that is not uncommon. Our many layers fail to keep us warm, and the colder-than-ice air feels like it is not stopped by our ridiculously bulky gloves. We eventually reach the summit, seeing at last its majestic crater below. The panoramic view from Misti’s Peak unveils the vastness of the Andean highlands and the White City at its foot.

If it is only half-way in distance, the return hike is a bliss! Running and sliding straight down the steep black slopes of the Misti Volcano without even looking for a trail anymore is an exhilarating sensation! We are soon almost too hot in the sun, but promised each other to never ever complain about it while we were 5,822 meters (19,101ft) above sea level!

Travel tips:

- All the trekking stats can be found in this interactive map below.

- Only a few agencies in Arequipa can set up this demanding trek with official mountain guide. Refer to Quechua Explorer.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

#6-Meet Juanita, The Ice Maiden of the Andes at the Museum Santuarios Andinos

In 1995, atop the Ampato volcano in the area of Arequipa at nearly 6,300 meters (20,700 feet) of altitude, an international team of archeologists made a discovery that would captivate the world. Nestled in a fetal position and perfectly preserved by the cold, the body of a young noble Inca girl emerged from the ice—untouched for over five centuries. Her name is Juanita.

While at the time of writing 23 sacrificed children have been found—16 in Peru, 3 in Chile, and 4 in Argentina, often sacrificed in as male and female pairs to reflect the duality of the world so dear to the Incas—Juanita, the “Ice Maiden,” was remarkably well-preserved and caught global attention with the Time Magazine making her part of the Top 10 discoveries of the year. Today, she lies at the heart of the Museo Santuarios Andinos in Arequipa, offering visitors not only an intimate glimpse into the spiritual and ceremonial world of the Incas, but also a unique face-to-face thanks to state-of-the-art technology.

Juanita was sacrificed in the 1450s as part of the sacred Capacocha ritual—an offering of the Incas to the gods in times of hardship or celebration. Chosen for her noble blood, possibly of royal descent, she was carefully draped in a finely woven red and white blanket—colors that symbolized blood, purity, and divinity—she wore a large metal shawl pin, its size an unmistakable mark of her elite status. Alongside her, priests placed precious offerings: gold figurines for the sun, silver for the moon, and seashells to represent the life-giving waters.

At just 14 or 15 years old, Juanita’s final journey began in Cusco, the capital of the Inca Empire. Over two months, she walked through traversed the rugged Andean terrain to the Ampato Voldano accompanied by a procession of around 50 attendants bearing offerings. Along the way, she was honored and revered as a sacred emissary. Her last stretch to the summit of the sacred mountain with priests must have been excruciating in the cold, wearing shoes of camelid wool and leather that would wear and tear on the abrasive slopes of the volcano. Exhausted, she was ritually given coca leaves and a very strong corn beer—chicha—before a ceremonial blow to the head ended her life to appease the gods.

For more than 500 years, Juanita remained atop the volcano, undisturbed, gazing east toward the rising sun. With all her internal organs intact and preserved in near-perfect condition by the extreme cold, Juanita is not a mummy as mistakenly referred to at times. While her face had suffered some damage from exposure, digital scans of her skull and DNA analysis have recently brought her features back to life. Today, standing before her at the excellent Museo Santuarios Andinos is a deeply moving experience. The beautiful young woman confronts us with a haunting humanity. She brings to life a civilization whose values and rituals can feel tragically alien in our modern world and still full of mysteries.

Travel tips:

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

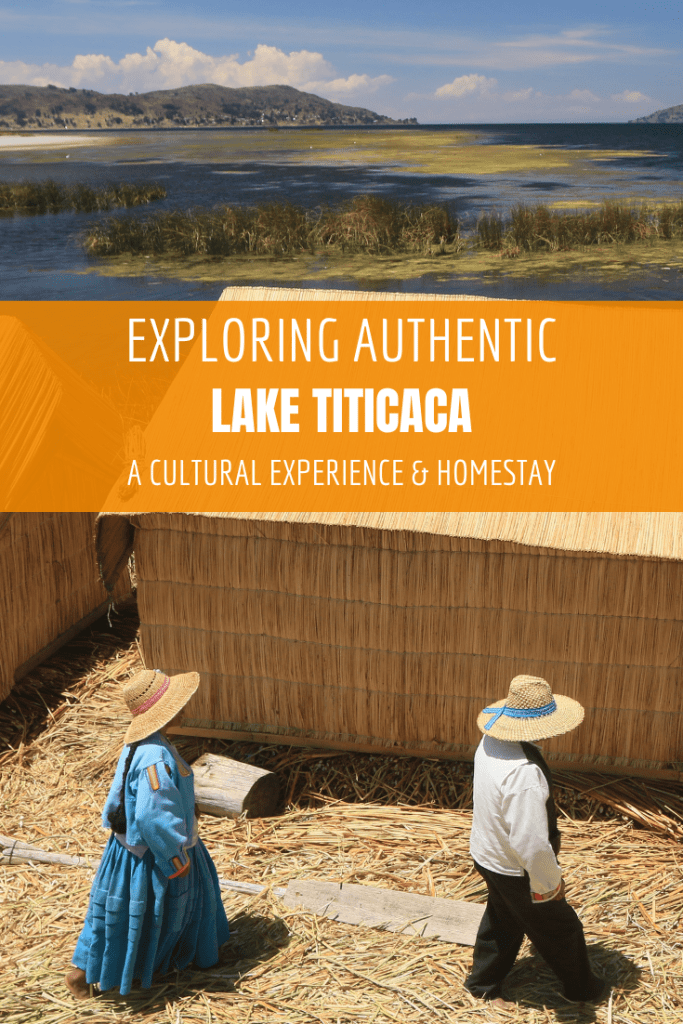

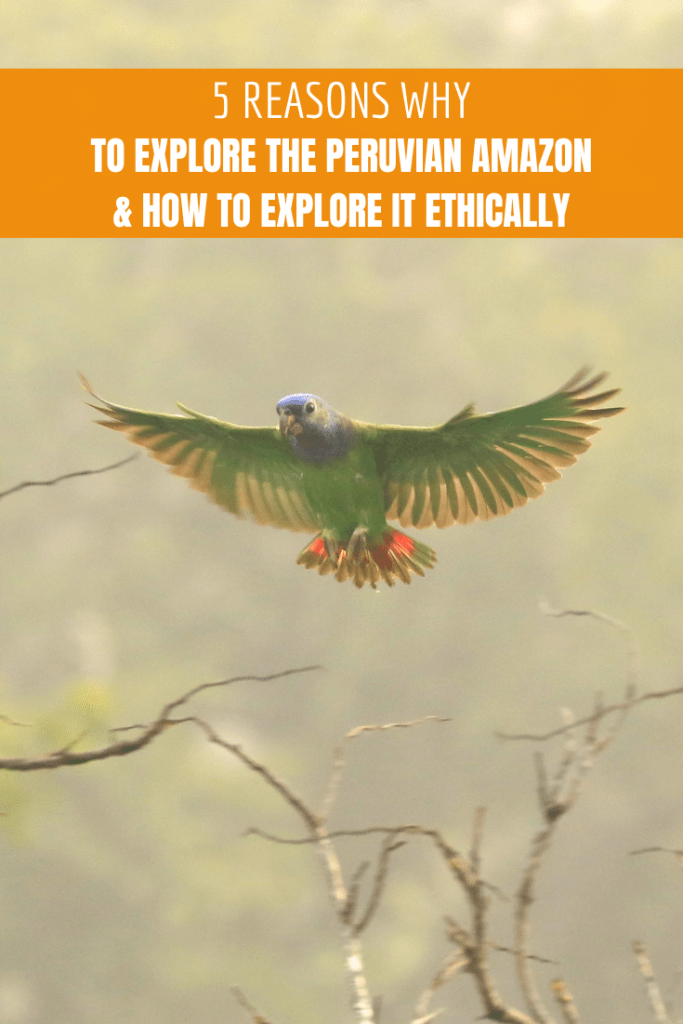

For more in Peru, click on these images: