Text: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

Photographs: Claire Lessiau

Pin it for later:

The highest tropical mountain chain in the world, the Cordillera Blanca

As the van gains altitude from Carhuaz to the starting point of our 10-day trekking adventure, tropical vegetation, cactuses, and bougainvillea line the bumpy dirt track. In the background, the snowy summit of Huascaran looks surreal. Huascaran is not only Peru’s highest peak, but also the highest peak in the Tropics. Small villages dot the track, women mend the steep fields, irrigated with water from the glaciers that is melting fast, growing potatoes, corn, peaches, blueberries, strawberries… Some transport their harvest in their colourful manta (a traditional piece of cloth) on their back or with the help of donkeys, others walk their sheep along the road: alpacas and llamas have long been replaced by these familiar helpers – the Spanish influence. Our official mountain guide Quique Apolinario Villafan exclaims: “this is the village where I was born,” as we are passing Amashca, towered by the majestic Huascaran Mountain. No wonder that with such an inspiration growing up, Quique wanted to reach for the Andes mountains! However, he was faced with barriers maybe even tougher to overcome than the altitude, steepness, and glaciers…

On the slope of the legendary Huascaran, the highest peak of the Tropics (6,768m; 22,204ft)

After passing a forest of eucalyptus planted for construction and agricultural purposes, fewer trees cover the slopes as we are getting close to 3,600 metres (11,811ft), the tree limit. Further up, only queñuales trees grow, with their weird-looking peeling orange bark that provides thermal insulation to their curvy trunks and allow them to grow at altitudes up to 5,000 meters (16,404ft), one of world’s highest trees. The van drops us off at 3,600 metres (11,811ft), at the foot of the trail to the refuge of Huascaran. We must hike up about 1,200 metres (3,937ft) of positive elevation to reach the refuge, and starting at 3,600 meters (11,811ft), the level of oxygen is already lower than what we are used to, and we get out of breath fast.

Past the forest of queñuales, the path gains altitude rapidly and leads us to ruins left by the Huari civilization. The walls are clearly visible and some ceramic pieces can still be found. “Probably a religious purpose,” Quique explains admiring the view on the valley with Huascaran behind.

With only 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) to hike, the gradient is clearly steep and we pace ourselves to make progress. The view is always a perfect excuse for a break, and even more so when the refuge is eventually in sight! Built with local granite, it is initially hard to spot, well camouflaged on the Huascaran Mountain which glacier and double summit tower it. “With only the help of mules, donkeys, horses, and about 500 volunteers we built it in a year: not a single helicopter was used,” Quique describes proudly as he was part of these volunteers. And when we enter the refuge, what a good surprise! The porters had already arrived and started the stove that provides a nice warmth, and snacks are quickly served with a coca tea to help with the altitude: 4,700 metres (15,420ft)! Used to some mountain refuges in the Alps, the comfort of this one with electricity, running water and warm showers running on solar are unexpected bonuses!

At sunrise, clouds from the night before have lifted and we can marvel at the surrounding peaks and the majestic Huascaran. Quique climbed it several times. Climate change makes its ascension trickier as avalanches are more frequent, causing casualties.

We cross massive rock slabs left by the retracting glacier in a technical downhill, sometimes helped by ropes. As we go down in the valley, the last traces of the deadliest accident in this mountain chain remain. “It was a Sunday, May 31, 1970. Everybody was listening to the national team soccer game on the radio. The Ancash earthquake stroke and triggered an 80-million cubic metre (2.825 billion cubic feet) mega avalanche of ice, snow and stones coming down at a speed of 280 to 335 kilometres per hour (175 to 210 miles per hour) from the Huascaran Mountain.” Quique explains looking at the new village of Yungay that is built on top of the rubbles of stones that instantly buried 20,000 to 22,000 people and the former village of Yungay. People thought they were protected, being higher up across the valley from Huascaran, but the strength of the mega avalanche did not leave them any chances. If traces are still visible, life has taken over and the valley of Yungay is well populated again with many fields…

How one man could change so many lives in the Cordillera Blanca: Father Hugo & the Don Bosco organization

A few days of walking later we find ourselves on the oriental side of the Cordillera Blanca, in a completely different valley famous for its first row (and safe) view on avalanches. From the village of Yánama where we visited the Don Bosco mission initiated by the angel of the Andes, the Italian Father Hugo de Censi, it is a relatively short hike up to the refuge of Contrahierbas (4,100m / ft). All the mountain refuges of Peru are located in the Cordillera Blanca, and all serve the same social purpose of empowering the local youth by creating jobs and revenue in their mountains. Today, the income produced from the mountain refuges of the Andes is pumped back into helping the people: over 1,500 houses have been built for the poorest families. On top of this, almost 1,000 trips per year to the refuges provide jobs to porters and mule leaders to supply them and support tourists.

As we enter the stylish refuge built in the style of the nearby pre-Inca Quisuar ruins with solar showers and running water, and escape the rain, Quique tells us more of his story. His life changed drastically and for the best thanks to the Don Bosco guiding school. In the wake of a ramping inflation in Peru in the 1980s and the destructive action of the Sentero Luminoso (also known as the Shining Path) guerilla group, as a teenager, Quique had to support his family, as a waiter, painter, or wood gatherer. Anything would do. Once, a friend of his who was a mountain guide offered him to come along a paid trip to take care of the donkeys for no pay but to gain experience. The tip Quique got from the two French customers represented more than a 2-week paint job, and with a deep passion for the mountains, Quique had found his vocation. But to become a mountain guide was a tall aspiration with no money to do so. Luckily, Father Hugo had just opened the free Don Bosco guiding school close to Carhuaz: Quique applied and shortly after, he received the letter that changed his life; he was in! Quique would become an official mountain guide… This is if following the strict religious instructions marked by tough discipline, making his bed, and cleaning the common areas before mass and attending class, spending the weekends helping the less fortunate, and working hard. This was not so easy, and of the 45 who started the instruction, only 18 graduated after 3 years.

Quique’s eyes get wet when he recalls getting his first salary: “I bought my mother a propane stove as until then she only cooked on wood. It changed her life.” And with his humility and gratitude towards Father Hugo, he omits to say that he supported his brothers financially in getting their education and saved some money to put himself through language school – a good investment as he fluently speaks five languages today, swapping with ease between Quechua with the porters, Italian, French, Spanish and English!

Second to none scenery

If Quique has become one of the best mountain guides of Peru and leads expeditions to the summit of the Aconcagua, the highest mountain in the Americas (6,961m; 22,838ft), today’s expedition leads us to one of his favourite spots in his backyard: the Mirador de Avalanchas.

Passing the Quisuar ruins dating back to the 6th or 7th century and already showing some anti-seismic techniques (using a 5-degree angle in the walls and small stones to absorb vibrations), the trail follows the Qhapaq Ñan (also known as the Royal Way or Inca Trail) and goes up via some glacier lakes along waterfalls to a viewpoint from where we can safely observe the avalanches on the backside of the Contrahierbas Glacier. The donkey leader and cook have set up a cosy camp, at 4,600 meters (15,092ft) of altitude, and pulled out yet another delicious meal in the cooking tent. Occasionally, a massive piece of ice breaks in an astonishing sound, making us all jump to observe the avalanche.

The avalanches continue throughout the night. Pursuing up along the Qhapaq Ñan, we get to see even more of the glacier until we reach the mountain pass of Punta Yanayacu (4,840m; 15,880ft) that puts us back in the Ulta Valley, on the western side of the Cordillera Blanca. Behind us, the view on the oriental side of the mountain range and the valley of Yánama; in front of us, the stunning valley of Ulta with its peaks, glaciers, blue lakes and Huascaran! We are at the line of the watershed: on the Huascaran side, every drop of water runs to the Pacific Ocean not even 100 kilometres (62 miles) away, while in the other side of Punta Yanayacu, it all runs to the Atlantic Ocean more than 3,000 kilometres (1,865 miles) away!

As we barely know where to look with these literally breathtaking views surrounding us, a majestic and rare condor circles around the pass!

A real physical challenge: trekking, mountaineering, climbing & glacier walking at more than 5,000 metres (16,500ft)

We have been acclimating for the last 8 days in order to conquer the very last stretch. We prepare our gear the night before in our camp in the low and comfortable Ulta Valley (3,900m; 12,795ft): crampons, ropes, harnesses, headlamps, a warm sleeping bag, a tent, gloves, bonnets, and many layers of technical clothing.

The cook Jorge manages to bake us pancakes in the cooking tent at 3:30 a.m. with a strong coffee straight out of the percolator. At 4:30 a.m., we are following the slow and steady pace of Quique, going up to the Huallcacocha Lake in the dark. Bits by bits, the snowy Huascaran reveals itself and the birds start singing in the forest of queñuales trees. We reach the lake when the sun is up, trying to warm up with its first rays. Our mountaineering gear is laid out for us: the donkeys cannot go any further and we see them turn around, freed from their load, and run home. Quique has arranged for three porters for our group of four, as we are ourselves carrying our own gear.

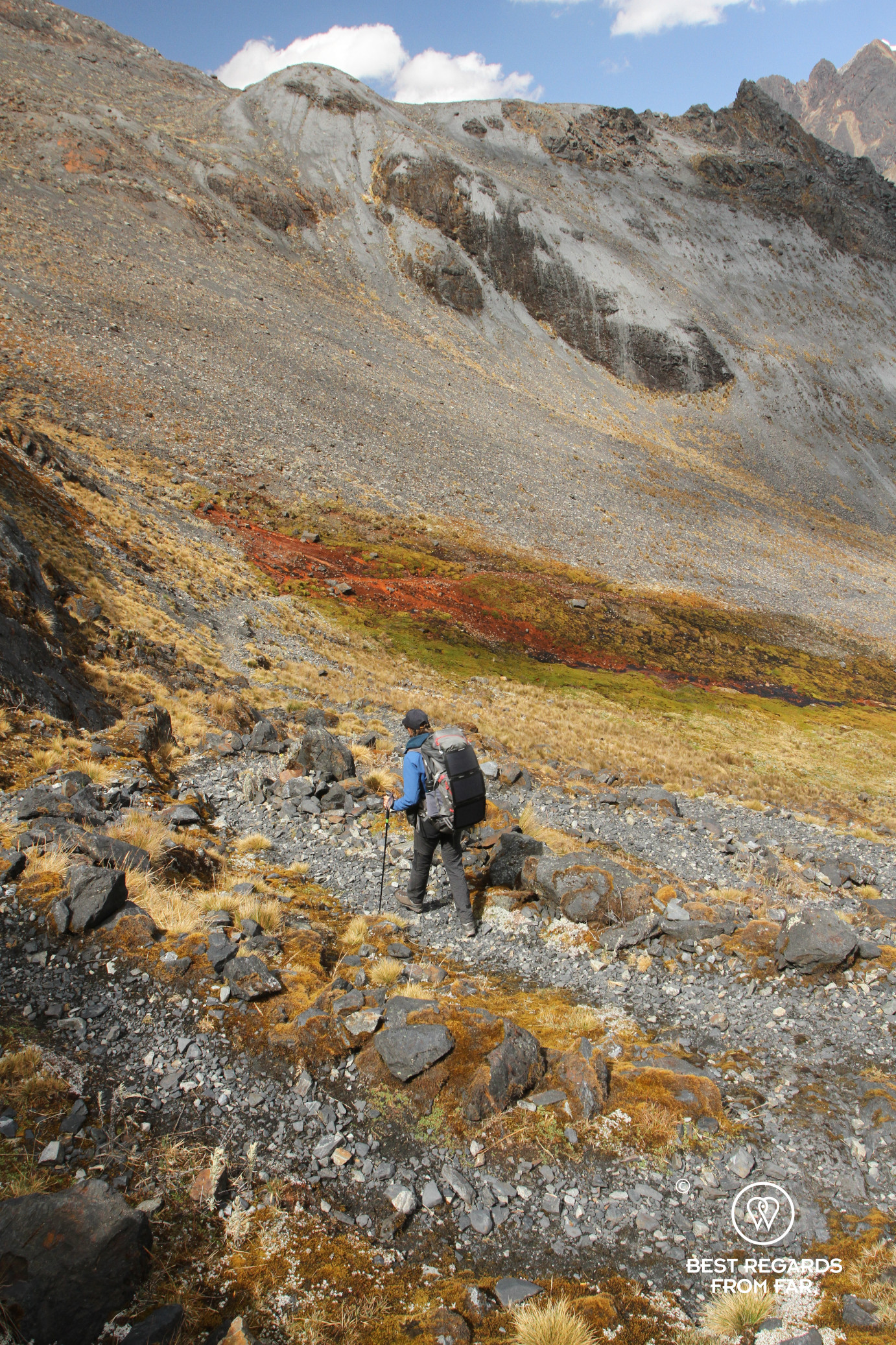

We repack quickly, and after these first 500 meters (1,640ft) of positive elevation, we continue steep up along a ridge line above the lake, and then through expansive plants that give us a hard time. “El Camino de los dioses” (or “the trail of the gods”) is the name of this circuit Quique put together and when I see the moraine coming up, I wonder why he called it this: probably because at any misstep, we are going to meet the gods right away! Progressing on the moraine on extremely unstable ground takes us some time and we eventually arrive at the foot of the 5,090-meter (16,700ft) Chequiaraju Pass. We start to climb an extremely vertical mineral world, not being able to trust even large boulders. At more than 5,000 meters (16,000ft), every effort costs us more and we really feel the weight of our backpacks.

We eventually make it to the top. We know we have to say goodbye to the now familiar Huascaran, and the mountain of Hualcán welcomes us in this new valley. But first, the glacier must be passed and we gear up with our crampons, roped to each other. As everywhere else in the world, the glaciers of the Andes retract fast and the crevasses are clearly visible: the utmost focus is required before switching to the unstable rock slabs. Soon, the turquoise Chelquiacocha and Auquishcocha Lakes can be seen, as well as our moraine camp, far in the distance: the porters have already set it up and must have been there for hours by now despite their heavy load of about 25 kilograms (55lb). After some more trail searching, we make it to camp, happy to have a warm coca tea and ready to pitch at 4,900 meters (16,076ft), with Hualcán Peak in front of us.

The Hualcán is the peak Quique climbed back in 2005 to graduate as an official guide. From the top, he could look at all his childhood below in his village of Amashca, and at all the surrounding gods, the way he refers to these majestic peaks of the Cordillera Blanca. One cannot help but think that with Quique’s humility and gratitude, the religious reference also echoes Father Hugo and Don Bosco, which are still changing lives here every day in this beautiful mountain chain, and beyond!

Travel tips:

- After years of work, sweat and suffering, Quique Apolinario Villafan runs his own guiding company, EXPE Perú, and is one of the best official mountain guides of the country, leading groups up the Aconcagua, America’s highest peak. EXPE Perú can customize any trip in the Cordillera Blanca and beyond, with a sweet spot for expeditions with porters, donkeys and cooks that are sustainable & responsible and that are not what every other agency does!

- This specific trekking is called el camino de los dioses.

- Before your trekking or to recover from it, the Wayarumi Sky Hotel in Carhuaz is an excellent option.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

For more in Peru, click on these images:

I need to get back to Peru! What an amazing journey. Your photos are stunning!

Thank you so much Anna, happy you find it inspiring 🤗 This specific area of the Cordillera Blanca is very authentic with incredible landscapes and very kind people. We highly recommend it!

More articles to come about Peru, stay tuned!