Text & photographs by Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

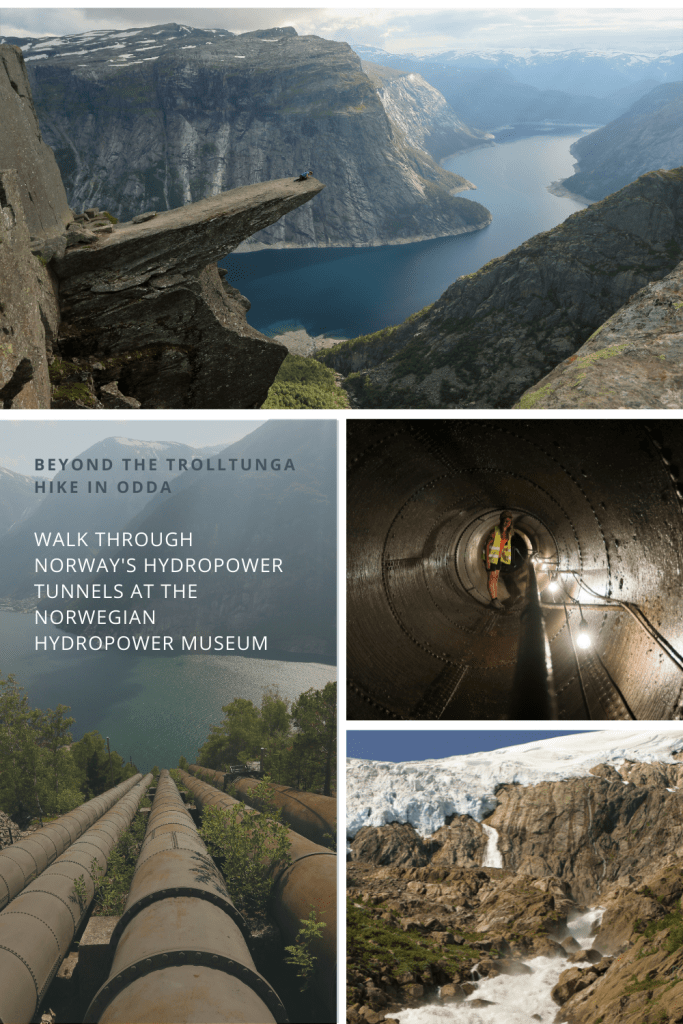

The steep green mountain slopes of Western Norway are covered with white veins. Immensely powerful waterfalls plummet into the crystal-clear or emerald-green waters of the fjords where occasionally a whale passes by… Standing on top of Lilletopp, Tyssedal, overlooking the Hardanger Fjord, I am facing two very different sides of Norway: to the right, it looks like a lost and wild place on Earth dominated by nature, to the left another impression sticks… In the midst of this natural beauty attracting hikers from all over to conquer the famous Tongue of the Troll, or Trolltunga, lays the heart of where the industrial revolution of Norway started and the cradle of the country’s hydropower capabilities…

Pin it (or bookmark it) for later!

Where many wealthy British tourists followed in the footsteps of the early mountain pioneers from the 1830s to marvel at the beauty of these majestic waterfalls created by melting glaciers or rainfalls, a few engineers realised in the 1890s that these very waterfalls at the Hardanger Fjord could become another kind of white gold. In the eyes of these engineers who started scouting nearby rivers, the three dozens of poor inhabitants of this rural area with its harsh climate who mainly survived from substantial farming had gold in their hands, or at least through their lands. In 1905, in the new independent Norway, the new era of hydropower was about to start!

What made the area so special was the combination of limestone, potential cheap hydroelectric power and logistics: the flat banks of the harbour of Odda seemed perfect to build factories to produce carbide to lit the prosperous British mines. In order to operate the British-owned Alby United Carbide Factories and the North Western Cyanamide Company, only a nearby powerplant was needed (back then, electricity could not be stored nor transported efficiently)!

It was a titanic job… I am above Tyssedal, merely a crack in the mountains along the Hardanger Fjord, only six kilometres from Odda, where the powerful Tysso cascade used to fall. On Lilletopp where I am standing after a rather strenuous hike, the granite mountain was dug out by hand to form gigantic reservoirs and tunnels to channel water from the nearby lakes of the Hardanger Plateau. Workers used to hang along the steep granite walls, barely secured by a few wooden steps and ropes. We have no idea of the number of casualties there might have been as many were not locals, but workers attracted by the well-paid yet dangerous job.

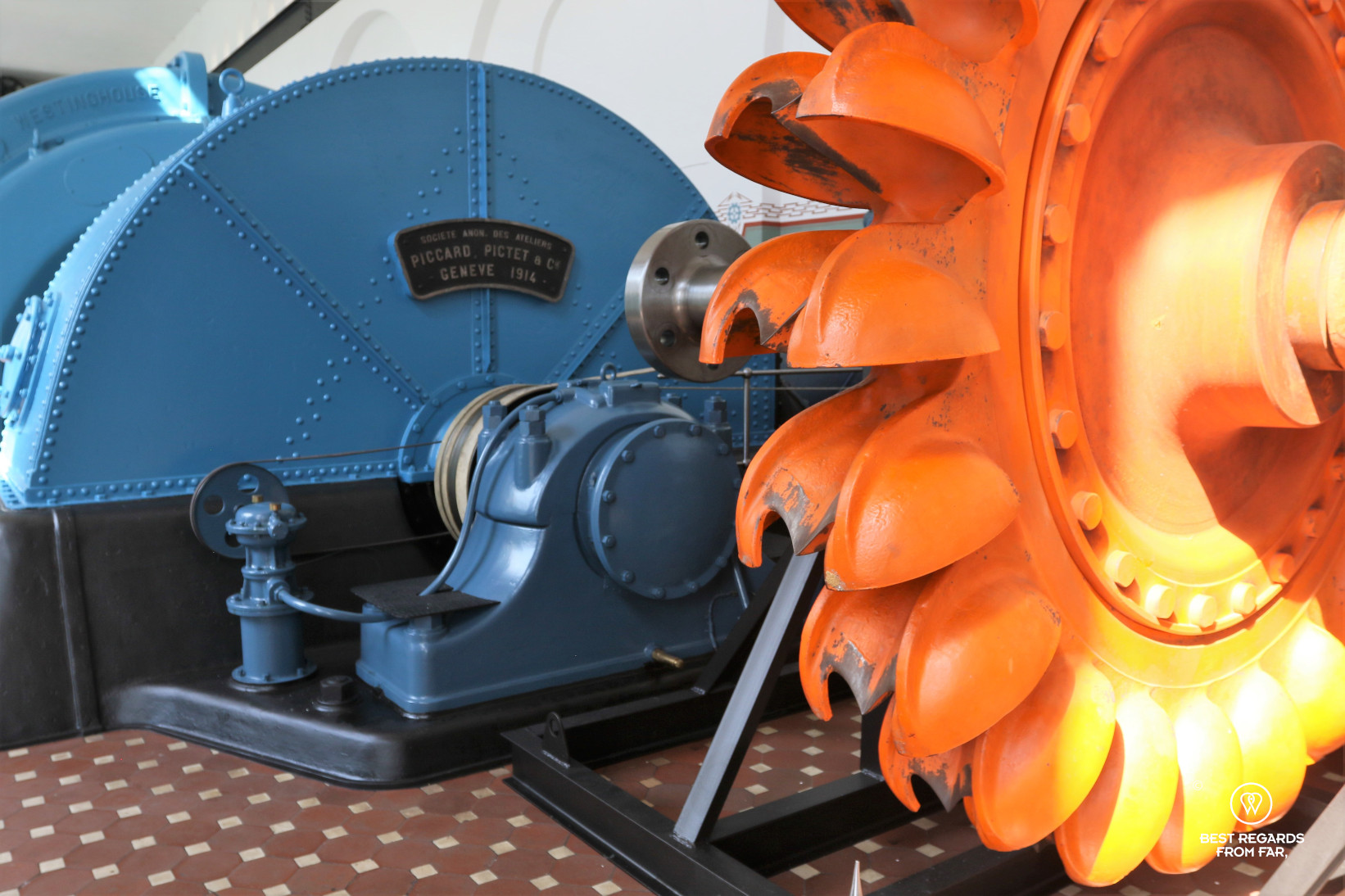

From the granite tunnels through which water used to flow until 1989, we follow our guide and enter, walking almost straight up, the 1.5-meter diameter stainless-steel water pipes made of hundreds of 7,500-kilogram sections. Too heavy to bring up one by one, each section is made of an assembly of smaller parts each brought up by horses or cabled up with a basic mechanism. All these pipes passed through the valve control room before bending to a steep 60-degree angle along the mountain and channelling the water over 400 vertical meters. This immense potential energy of the water spun the rotors of the turbines in the hydropower plant along the fjord. This kinetic energy was then transformed into electricity in the generator. In 1908, after only two years of harassing work, the capability was showcased and the powerplant started running.

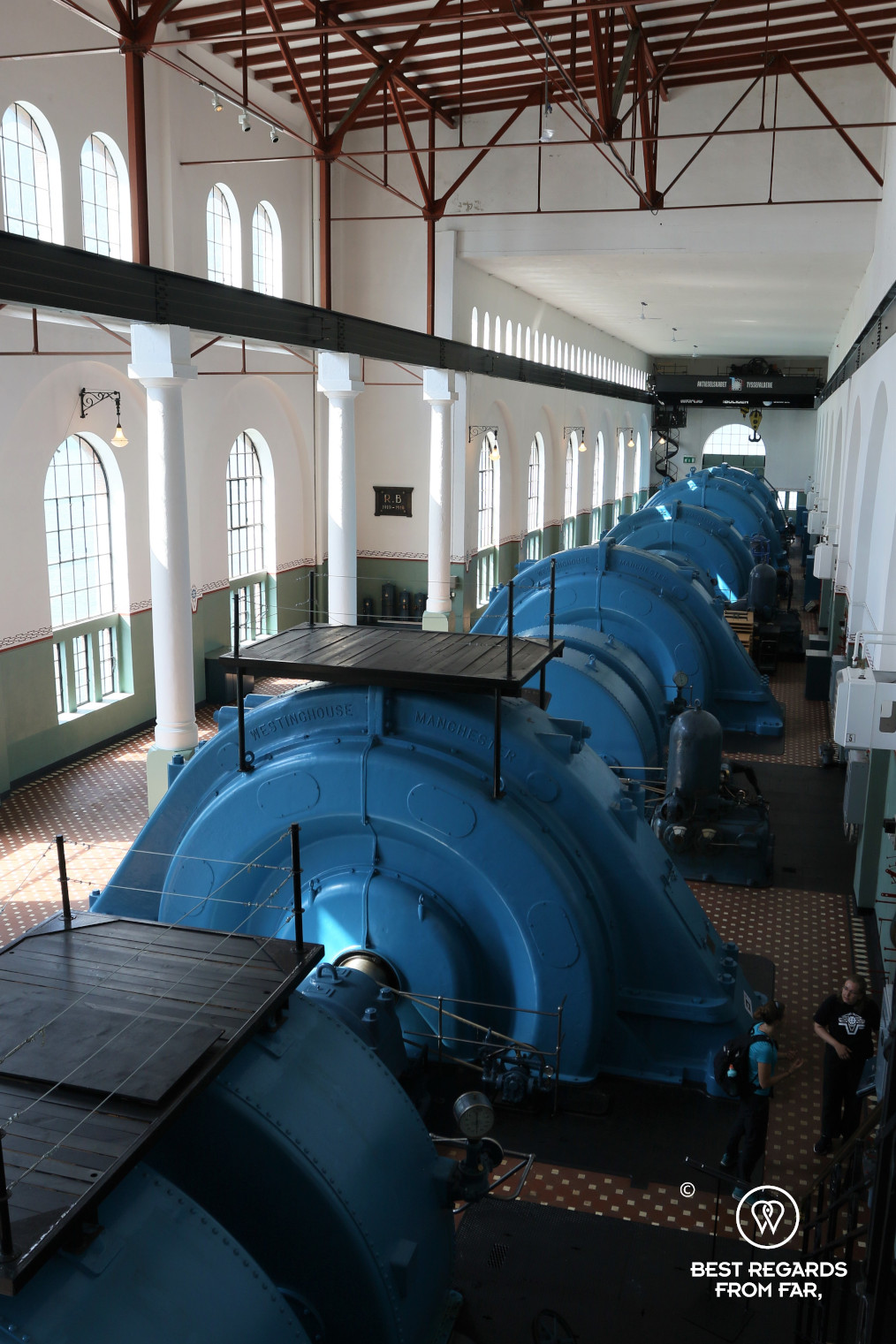

At the forefront of progress, the plant itself was a vitrine: Oslo architect Thorval Astrup designed a beautiful building with arches, murals, and a control room with marble countertops.

When the powerplant was completed in 1918, five water pipes supplied 15 Pelton turbines generating 100 megawatts (about 10% of Norway’s total electricity production then). The hydroelectric plant of Tyssedal became the largest in the world, alongside world’s largest carbide factory! Peaceful Odda got transformed into an industrial town kicking off the industrial revolution in Norway, and starting the country’s hydropower age. Workers settled in, enjoying electricity, hospitals, schools…

However, industrial crisis hit Odda. The fjord had turned into a chemical dump. Fish had disappeared. The beautiful waterfalls were piped. Another type of challenge had started for the resilient inhabitants…

Today, Odda has recovered. The powerplant was turned into the excellent Norwegian Museum of Hydropower. The pipes are lined with a via ferrata. Lilletopp has become a local’s favourite hike and viewpoint. The water of the fjord is clean and fish are back. The city is booming again thanks to tourism and hikers who want to stand on the famous Trolltunga or explore the nearby Folgefonna Glacier.

Electricity is still cheap and plentiful. It is now generated by one massive turbine: tunnels are built inside the mountain and supplied by the 1918 Ringedal Dam at the start of the Trolltunga hike. The early hydropower plant of Tyssedal has led Norway to become a hydropower nation, bringing wealth to the country and renewable energy that still accounts for 98% of Norway’s electricity today.

Travel tips:

- Note that the main hall of the excellent Norwegian Museum of Hydropower has great acoustics: concerts are hosted regularly with a fantastic view on the fjord and its waterfalls.

- A much easier alternative to the Trolltunga is a hike up Lilletopp. Once you have visited the tunnels, make sure to push higher up and enjoy the view on the Hardanger Fjord and Odda.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles and photos (zoom out) about the area (short tutorial)!