Article updated on December 27, 2024

Text & Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

The world-famous temples of Angkor are a marvel—magnificent, monumental, and rooted in centuries of history. Yet, with over 4 million visitors each year, most of whom flock to just a handful of temples during the dry season, it is easy to lose the sense of magic that once filled the capital of the vast Khmer Empire. However, there is a way to experience Angkor in a more intimate, authentic light—by getting off the beaten path and onto the winding jungle trails that wind between its majestic ruins.

Pin this article for later!

Pedaling Through Time

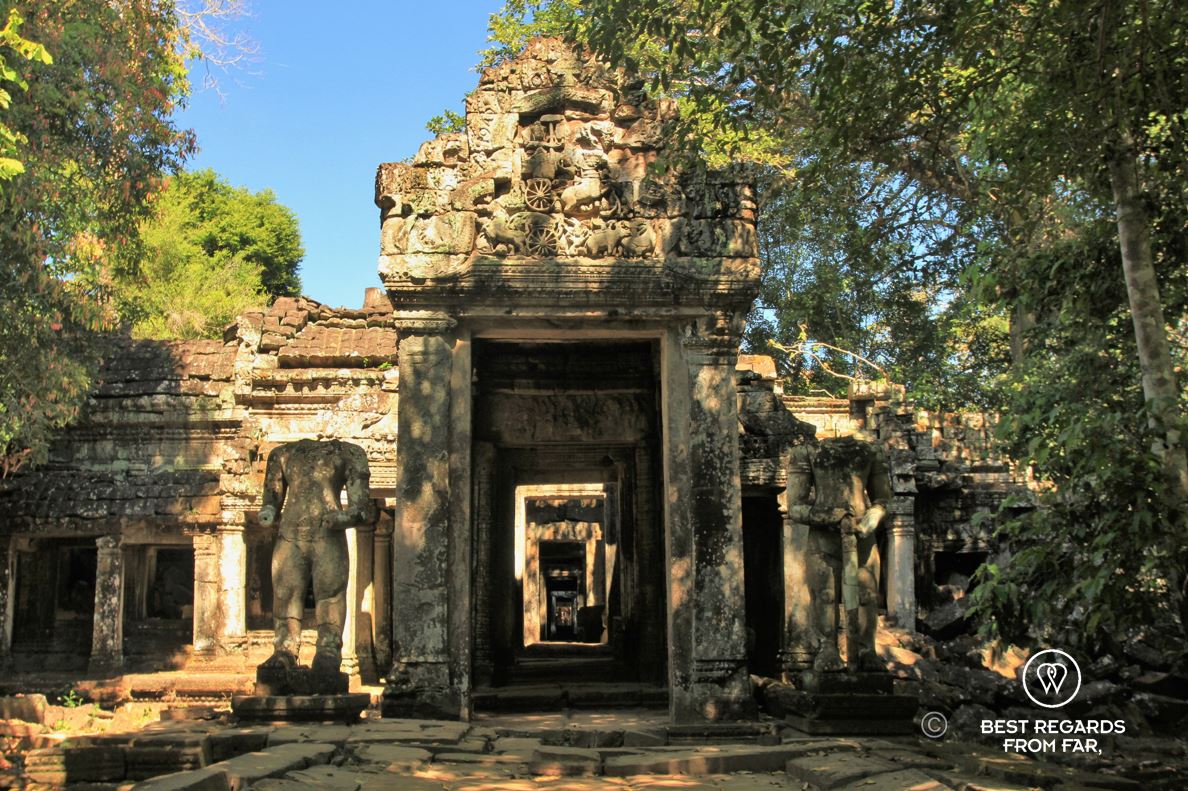

The early morning sun filters through the dense Cambodian jungle as I skillfully steer my mountain bike along a narrow single-track path, dodging sharp rocks and twisted roots. In front of me, half-swallowed by the ever-present aerial roots of strangler fig trees, looms the centuries-old Khmer temple of Preah Khan. Birds chirp in the thick greenery, butterflies dart through the shafts of sunlight, and a lazy cat stretches on the ancient stone steps as if time itself had stopped in this serene corner of Angkor.

We have risen early to beat the crowds, but not as early as the many tuk-tuks filled with tourists already heading back to Siem Reap after the popular sunrise tour at Angkor Wat. Our guide, Sarith, expertly leads us on lesser-known trails as we approach the northeastern corner of the 200-metre wide and 6-kilometre long moat surrounding Angkor Wat, the world’s largest religious monument, the site’s most acclaimed temple, and one of the most iconic symbols of Southeast Asia. Here, far from the crowds, Sarith pauses and shares his wealth of knowledge.

Unlocking the Mysteries of Angkor Wat

Seated on the ancient stones of the moat, Sarith begins to decode Angkor Wat and Khmer temples. “This state temple was built by King Suryavarman II in the early 12th century,” he explains. “It is dedicated to the Hindu deity Vishnu and designed a miniature representation of the Hindu universe. The five central towers represent the peaks of Mount Meru, home to the Hindu gods, surrounded by other mountain ranges and the cosmic ocean—the moat—and a bridge adorned with naga sculptures (the sacred multi-headed mythological snake) links the human world to the divine.” Sarith’s words paint a vivid picture of the site’s rich symbolism and tumultuous history that followed its construction, including the brief Cham occupation before the compassionate and loved King Jayavarman VII reclaimed the site, expanded the Khmer Empire, and introduced Buddhism to Angkor that ultimately became the state religion.

Exploring Angkor Thom & the Bayon

We set off again to explore the capital of this influential king, Angkor Thom, just a few kilometres north, where he built Ta Prohm, Preah Khan, and his state temple Bayon. We cycle past the bustling South Gate of Angkor Thom, the grand entrance to the ancient city for ordinary people. The magnificent stone sculptures of gods and demons—54 of each on each side of the bridge echoing the 54 provinces of the Khmer Empire—carry the naga above the wide moat of Angkor Thom. Hundreds of tourists pass us, but our path soon veers off the main route onto a narrow dirt track atop a fortified wall towering the 13-kilometre-long moat that it circumnavigates. As we bike towards the West Gate that was used by slaves, we are rapidly away from the crowds. Local women in canoes collect bright pink lotus flowers from the moat, oxes bathe and kids swim. Life seems to have remained remarkably unchanged for centuries, catching glimpses of the medieval Angkor. Back then, the causeway would have been busy with ox-carts, elephants carrying stones for constructions, hundreds of workers walking to the building sites, and a few dignitaries carried on portable hammocks by their vassals.

As we pedal away from the moat, we enter the grounds of Angkor Thom, and we make our way toward the Bayon Temple, famous for its gigantic smiling stone faces—216 of them, carved into 37 towers out of the 54 originally built. The faces, serene and enigmatic, overlook the site in all four cardinal directions, adding an aura of mystery to the temple.

“Some believe these faces represent Lokeshvara, the Bodhisattva of compassion, while others think they depict King Jayavarman VII himself,” Sarith debates, guiding us through the labyrinthine corridors. The intricately carved bas-reliefs that cover the temple’s walls depicts vividly the daily life of 12th-century Khmer people. 11,000 carved figures are represented in scenes of battle, court life, and mythology taking us back to the splendour of the Khmer Empire.

As we continue to explore Angkor Thom, we make our way to the Terrace of the Elephants, a royal viewing platform where the king would attend royal parades and listen to complaints from his subjects. Royal parades would be the most impressive ones, with elephants and horses covered in gold marching amongst palaces decorated with flowers. On major religious events, fireworks would reflect in the gold-cladded temple towers.

From here, Sarith tells us that Angkor was the largest conurbation in the world before the Industrial Revolution, with a population of around 750,000—larger than London at the time. This required strict rules: while the South Gate was for ordinary people and the West Gate for slaves, the North Gate was only used by the king. The east side two gates connected the city to the outside world: the Victory Gate for the king and his victorious soldiers returning from battle, and the Ghost Gate, which was reserved for defeat, also allowing the bodies of the fallen soldiers to be carried back in the city. Our ride takes us to the quieter, more atmospheric Ghost Gate, a much less-visited entrance to Angkor Thom, where dense jungle has reclaimed much of the surrounding stonework. Here, we pause to reflect on the astonishing scale of the city, now lost in time.

Into the Jungle: Ta Prohm & Ta Som

Riding deeper into the jungle, we pass through rural villages where life flows at a pace unchanged for centuries. The women, seated in front of stilted bamboo homes, tend their gardens or sell goods at the local market. Men drive tuk-tuks into Siem Reap, while children practice their English with tourists at the main temples selling some cheap souvenirs. As we ride past rice fields, a woman is washing cloths in the tranquil barays (retention pond that was part of the extensive hydraulic network that allowed the Khmers to not depend on seasons for their agriculture) while a man is fishing.

At Ta Prohm, one of Angkor’s most famous temples dedicated to Jayavarman VII’s mother, tourists swarm to take selfies, as it was famously used as the setting for Tomb Raider, starring Angelina Jolie. While this temple’s towering tree roots and crumbling ruins are captivating, we find a more peaceful experience at the lesser-known monastic complex of Ta Som. Here, the jungle holds sway over the temple, its massive fig tree roots winding through the stone doorways. The intricate carvings of apsaras (the alluring celestial dancers who served as messengers between humans and gods), delicate libraries and reliefs half covered in lichens create a serene atmosphere, far removed from the hordes of tourists.

Preah Khan

The galleries and doorways of Preah Khan seem to form a labyrinth while the ever-present jungle and banyan trees swallow some of the stone structures.

After navigating through muddy trails, crossing rivers, and jumping over roots in the forest, the fortified walls of Preah Khan appear. Another of King Jayavarman VII’s grand temples, it was built on the site where he finally defeated the Cham invaders. Dedicated it to his father, Preah Khan was also a university and Buddhist monastery, symbolizing the union of Hinduism and Buddhism. The South Gate, adorned with a Garuda—the powerful bird that is the reincarnation of Vishnu—standing on a snake—that protects the Buddha—, epitomizes this fusion of beliefs. As we explore the vast, labyrinthine galleries, the temple seems to stretch into the jungle, swallowed by banyan trees.

Building Techniques & Back to Angkor Wat

As we make our way back via the unfinished Ta Keo temple, a millennium-old structure from 968, Sarith describes the building techniques of the time. The sandstone blocks, sourced from the Kulen Mountains 50 kilometers north of Siem Reap, were transported on bamboo rafts on the network of canals used for both transport and irrigation. Once on land, the stones were loaded onto elephants and carried to the temple grounds, where they were meticulously positioned and shaped through friction—without the use of mortar.

We cycle back to Angkor Wat to enjoy a quieter moment on the majestic archeological site. I am trying to imagine the lotus-shaped towers covered in gold and contrasting with the white-plastered walls. I study the details of the bas-reliefs that are covering the gallery walls from floor to ceiling. Carved by hundreds of skilled artists, they tell the stories of the Khmers on the longest continuous bas-relief in the world. With expressive faces and a remarkable sense of perspective, this masterpiece depicts epic scenes such as the battle of Kurukshetra, the royal procession of Suryavarman II (with traces of gold on his figure hinting at the past splendour of the galleries), the battle between gods and demons. Among the most iconic scenes is the Indian epic of Churning of the Sea of Milk, where devas (gods) and asuras (demons) work together, under the guidance of Vishnu, to churn the ocean and produce the divine elixir of immortality.

Reflections on the Lost Empire

The Khmer civilisation dominated mainland South East Asia for almost 600 years (9th-15th century). What could have triggered the collapse of such a powerful empire? Invaders? A shift to marine trade? A religious change? Sarith shares commonly-admitted thoughts on the decline of the Khmer Empire. The most probable hypothesis is that what made the greatness of Angkor triggered its loss. The advanced hydraulic system originating in the Kulen Mountains with canals, dams and retention ponds that once supported the empire’s vast population, year-round with overflow channels during the monsoon and irrigation channels in the dry season, eventually became its downfall. A failure in the waterworks made Angkor vulnerable to extreme weather. With the dramatic droughts of the late 14th century to the early 15th century, the conurbation could not feed every one, leading to social unrest. Stuck between the Chams to the east and the kingdom of Ayutthaya to the west (today’s Thailand), it is eventually the Siams who took over the weakened great city in 1431.

As the day draws to a close, the temple’s quiet beauty feels all the more profound after our day spent cycling through its jungle-clad ruins, starting to get an idea of the grandeur of the Khmer Empire and extent of its Angkor temple complex.

Travel tips:

- To live this adventure and discover the Angkor temple complex off the beaten path by mountain bike, please refer to KKO.

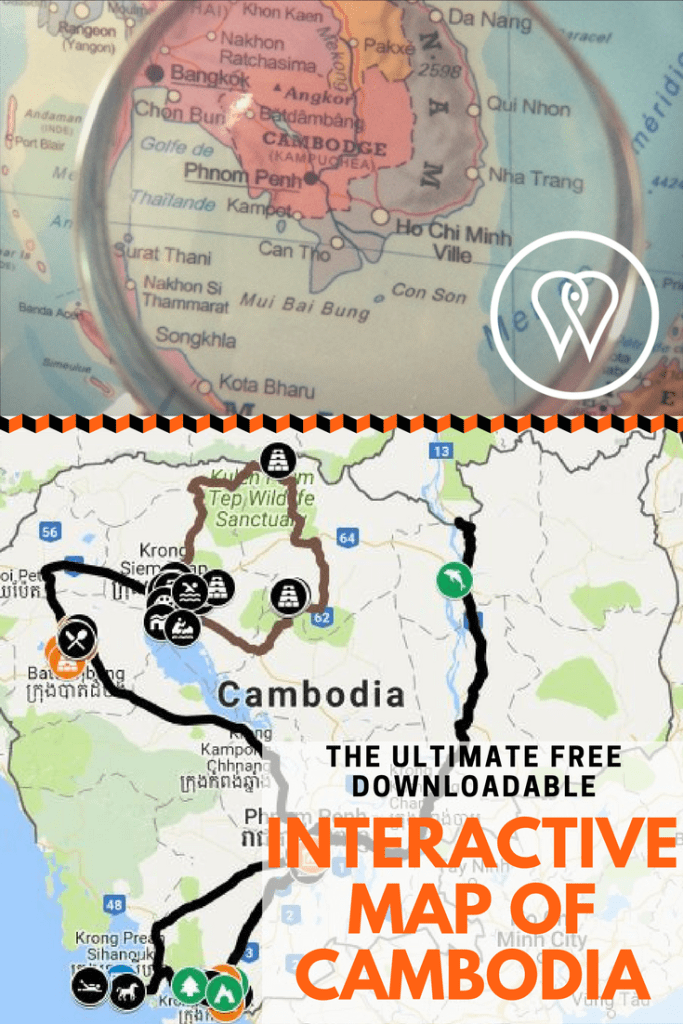

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles and photos (zoom out) about the area!

For more in Cambodia, click on the following images:

Beautiful photography!!

Thank you Anna! Good to hear that it is worth carrying our heavy cameras and lenses 😉