Article updated on December 28, 2024

Text & photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

It is a group of uninspiring, rather ugly three-story buildings with the typical architecture from the 1960’s surrounding a central yard. Chao Ponhea Yat high school was built in 1962 in the south of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. On April 17th, 1975, when Pol Pot marched on Phnom Penh with his Khmer Rouge troops, this high school was turned into the S-21 prison, also known as Tuol Sleng, the largest in Kampuchea Democratic where an estimated 20,000 people were jailed and tortured before being exterminated in the nearby killing fields.

Pin this article for later!

The story of Cambodia’s suffering is inextricably tied to its turbulent history. After nearly a century of French colonial rule, the Kingdom of Cambodia was restored in 1953. However, the country’s struggle for peace was marred by the Vietnam War (1955-1975), which spilled over its borders, as it did in neighboring Laos. The apparently neutral monarchy allowed the North Vietnamese communist Viet Cong forces to use Cambodia as a sanctuary and for its supply lines, leading to the bombing of the country by the USA. In the wake of this devastation, millions of rural Cambodians fled to the cities to escape the bombs. The population of Phnom Penh skyrocketed to several million inhabitants. In 1970, US-backed Lon Nol overthrew the monarchy and took power after a coup. The Khmer Rouge rebels, a communist formation led by Pol Pot, rose in opposition, backed up by red North Vietnam.

Lon Nol did not last for long and was deposed when the Khmer Rouge walked on Phnom Penh on the 17th of April, 1975. Pol Pot turned Cambodia into Kampuchea Democratic, his vision of a communist agrarian utopia with at its core self-sufficiency, dictatorship of the proletariat, total economic revolution, and complete transformation of Khmer social values. This vision quickly devolved into a nightmare as the regime implemented the Khmer Rouge radical policies completely reshaped the Cambodian society.

In just three days, the Khmer Rouge emptied Phnom Penh. Residents were forced—at gunpoint—to abandon the city to march to their native villages with nothing but the clothes on their backs and a rice bowl in hand. Many died along the way from exhaustion, hunger, and the brutal April heat. Those who survived were subjected to grueling labor on collective rice farms, working twelve hours or more each day in horrific conditions, with only a small portion of boiled rice to survive on. At the core of Pol Pot’s ideology was the notion of self-sufficiency, and this meant that rice production had to be immediately tripled across Kampuchea Democratic. For many, particularly those from the cities with no farming experience, the relentless labor led to death.

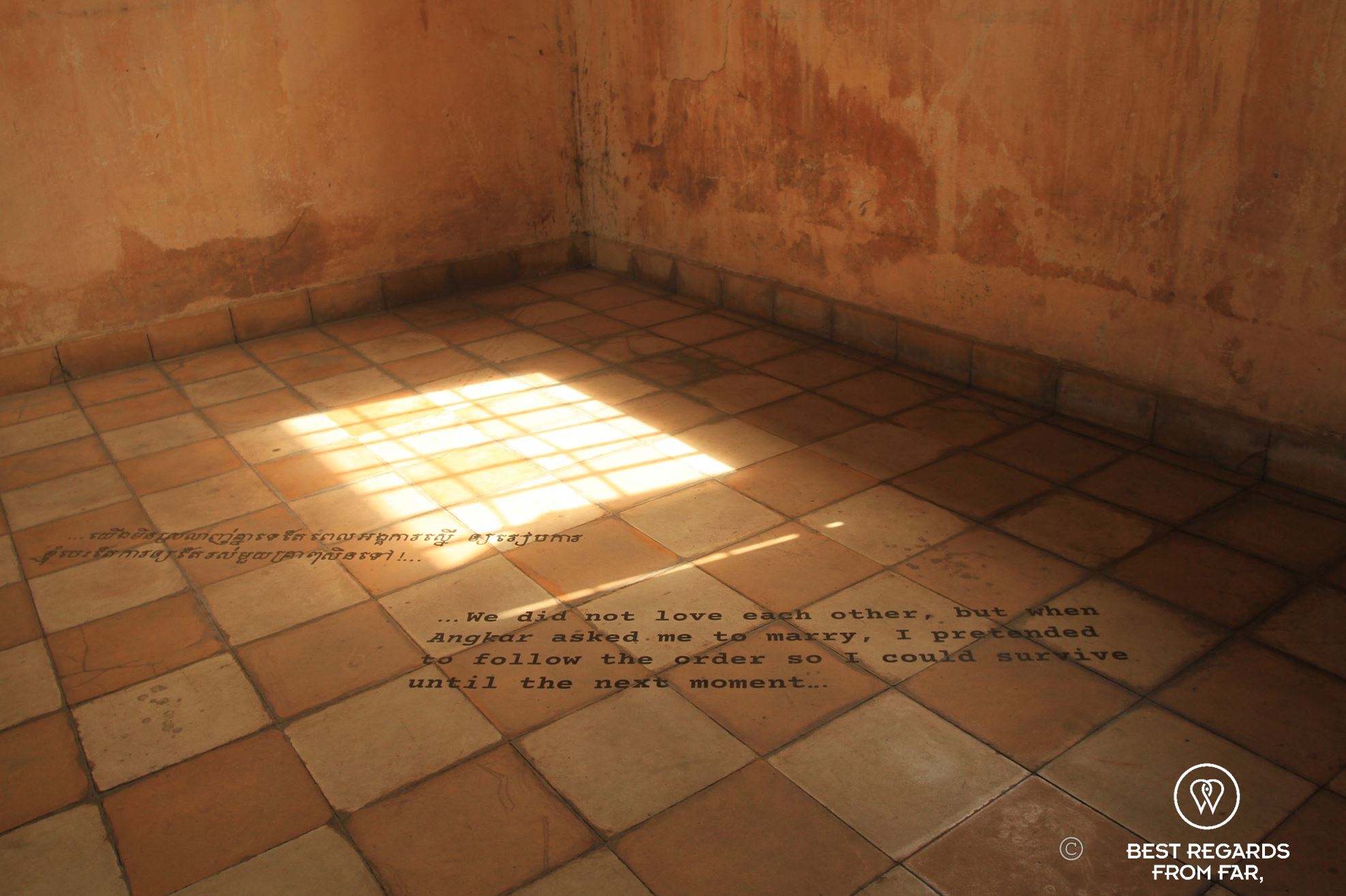

The Khmer Rouge imposed absolute loyalty to the communist regime, stripping the Cambodian people of their cherished values, beliefs, education, religion, and Khmer culture. Cambodia was transformed into a rural, classless society, where family bonds were shattered. Forced marriages were implemented as part of Pol Pot’s scheme to rapidly increase the population and achieve his vision of self-sufficiency. Newlyweds were spied upon on their wedding night, and if the marriage was not consummated, they faced execution. The regime’s relentless pursuit of ideological purity knew no bounds, turning the most intimate aspects of life into instruments of control.

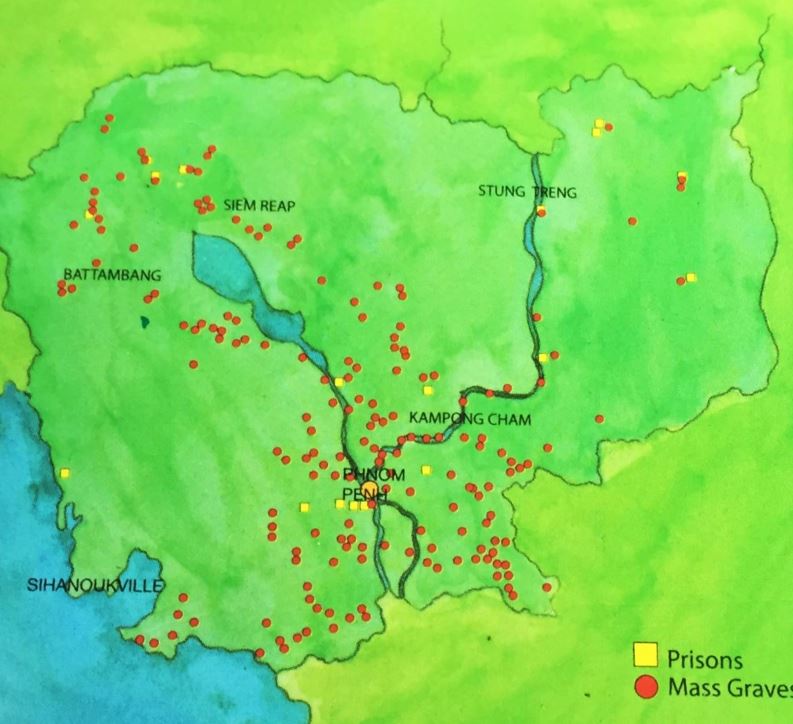

The paranoia of Kampuchea Democratic lead to many arrests often for treason. Urban dwellers, intellectuals, and anyone perceived as a threat to the regime were systematically arrested, tortured, and killed by the Khmer Rouge. Even the most trivial signs of education—such as wearing glasses, having soft hands or speaking a different language—were enough to send a person to S-21—the most infamous—or another of the 195 prisons operated during the regime.

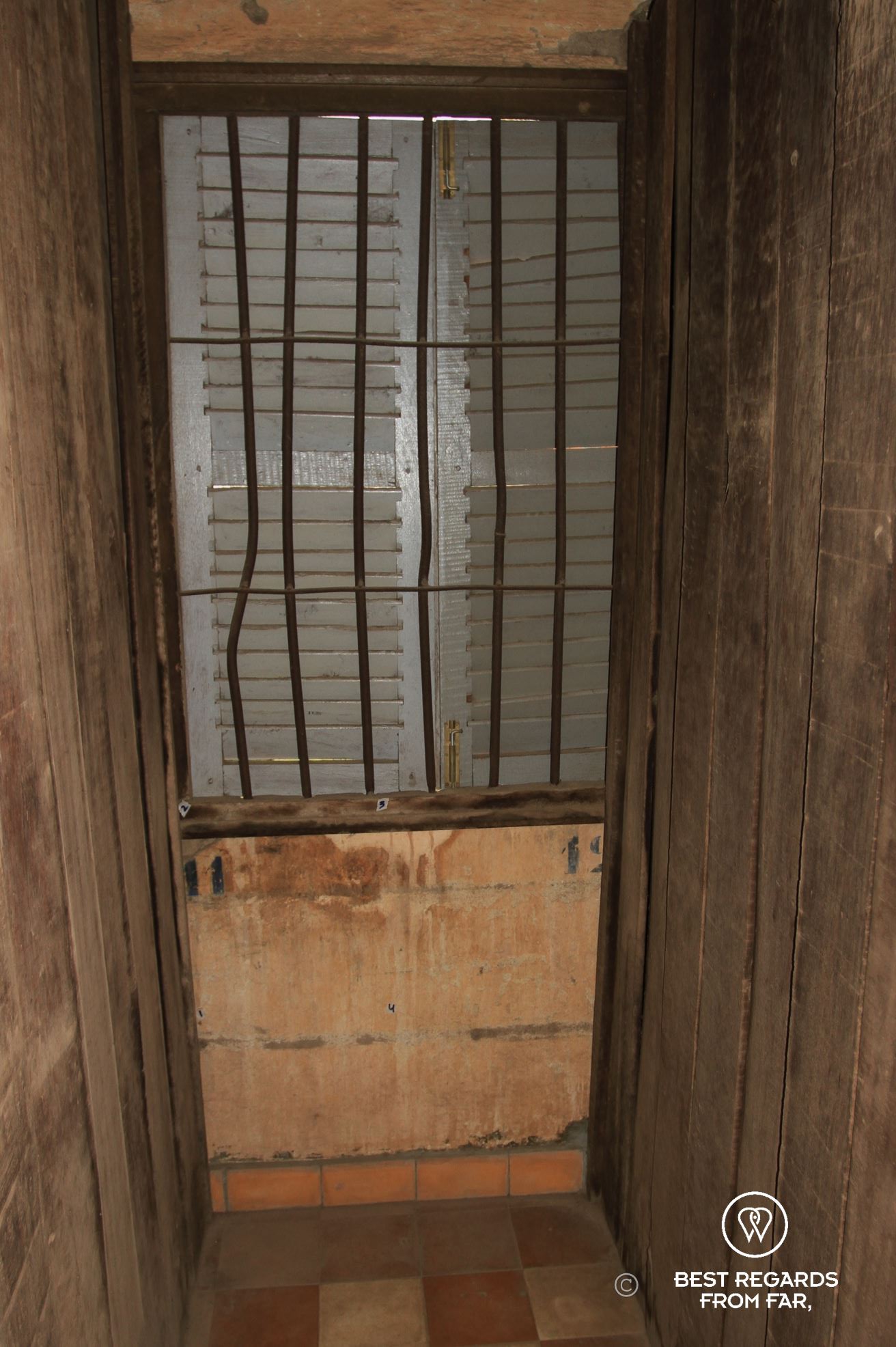

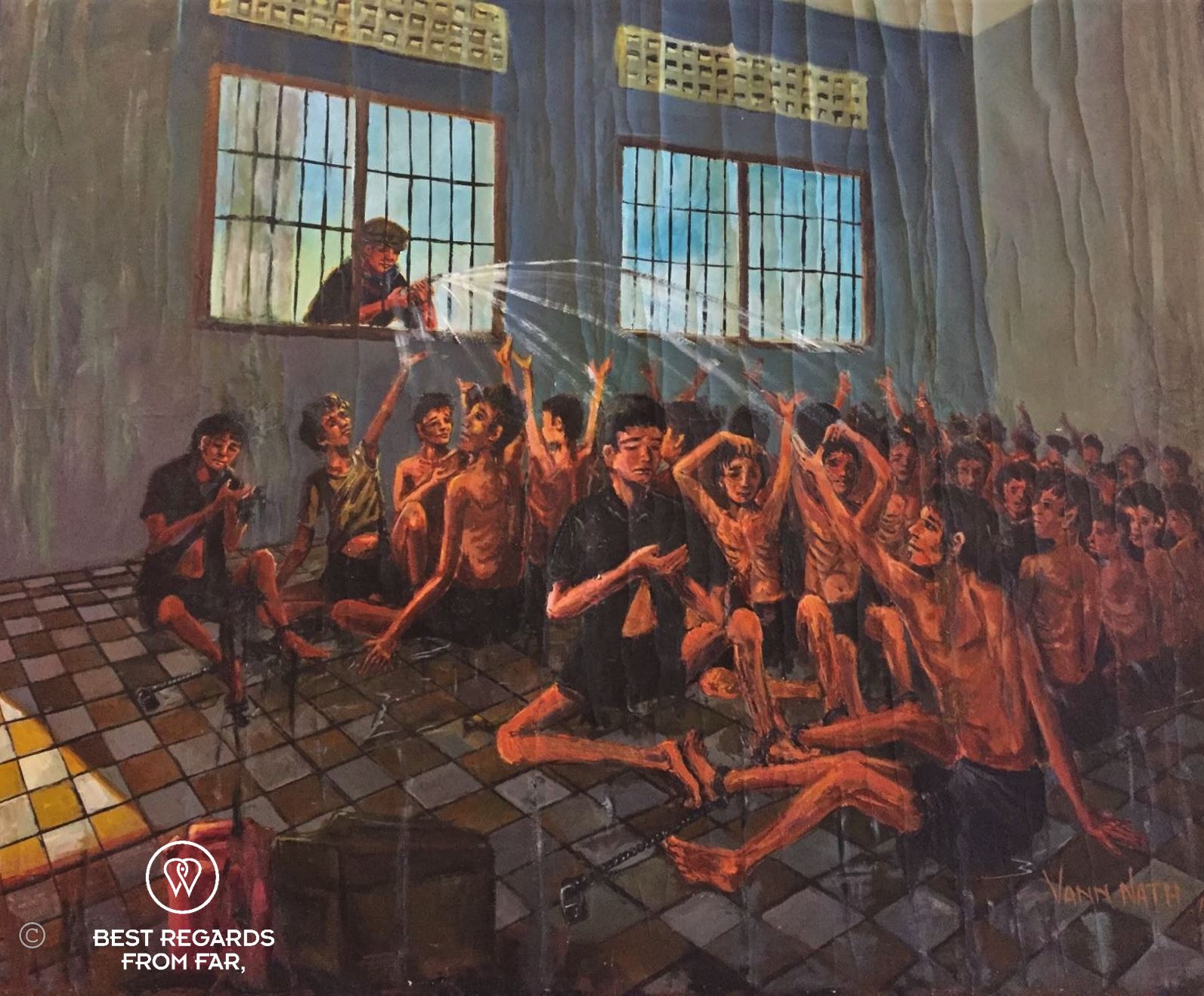

Victims of the Khmer Rouge were brutally tortured and coerced into falsely confessing to crimes against the revolution. The regime promoted the idea that education had no value, emphasizing instead the need for hard work and revolutionary loyalty. S-21, once a place of learning, became a place of unthinkable cruelty. All across the country, school buildings were repurposed as warehouses and prisons, with classrooms converted into individual cells or cramped, filthy cells for mass detention. School desks were replaced by metal bed frames, used to torture prisoners with electric shocks or searing hot metal. Gym equipment was modified to hang victims, while traditional methods of torture—such as sleep deprivation, nail extraction, waterboarding, and forced humiliation by forcing prisoners to eat their own excrements—were regularly employed. Some prisoners were subjected to horrific “medical experiments,” including organ extraction without anesthesia and blood draining. Many innocent people made up confessions, claiming ties to the CIA or KGB to end their suffering. By 1978, the regime began to crumble under the weight of its impossible demands and severe mismanagement, with even Khmer Rouge soldiers themselves falling victim to the same brutal treatment, imprisoned, tortured, and executed.

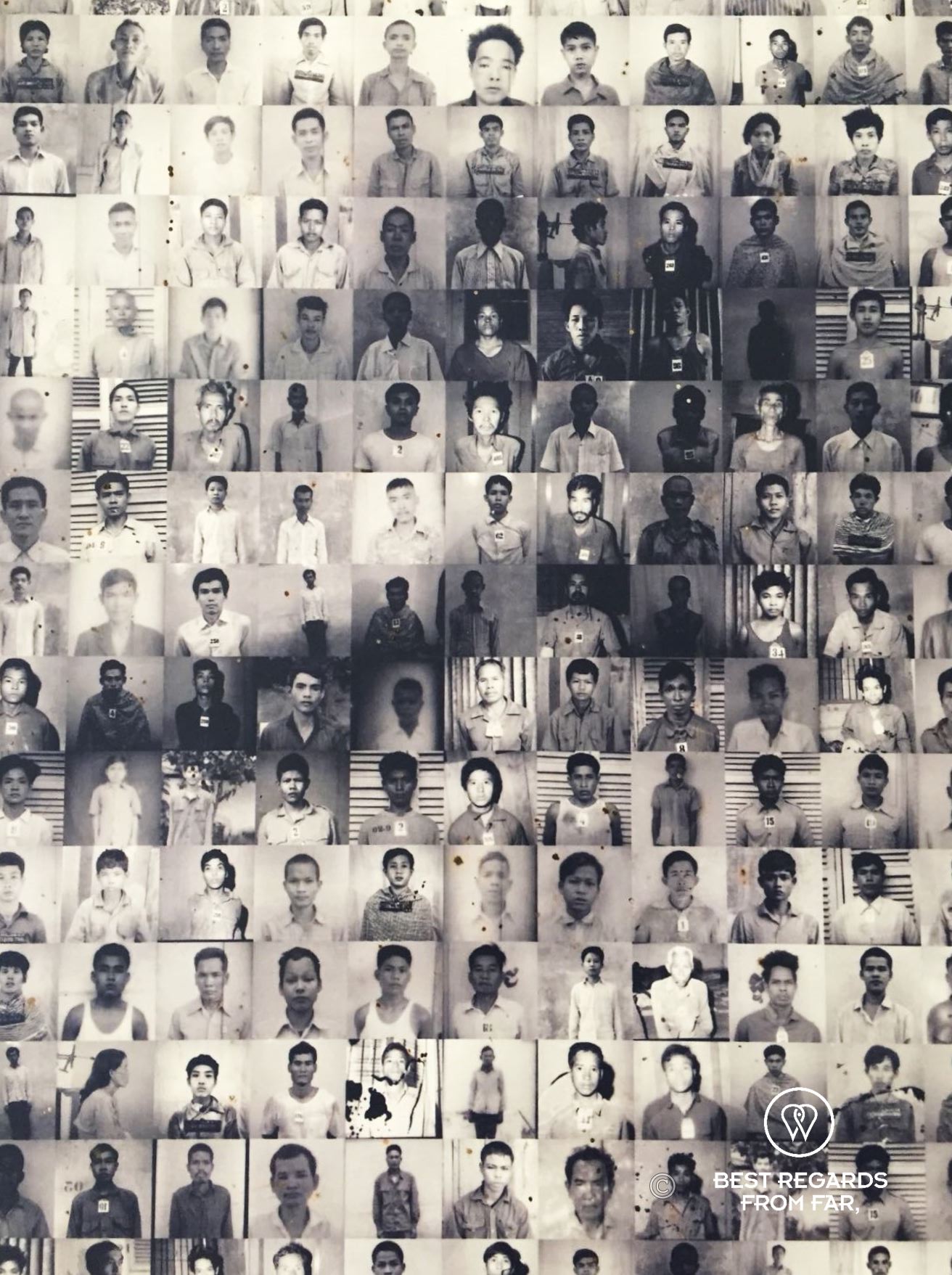

With a knot in my stomach and feeling nauseous, I meet the eyes of the sentenced victims whose black and white ID photographs that were taken methodically as they were brought in as they stare back at me from the walls. In their eyes, I read despair, pain, anger, fear, emptiness, confusion, bewilderment, or numbness. I am in one of the former classrooms of S-21, also known as Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, which used to be a mass-detention cell. The prison’s appalling history is preserved through disturbing photographs of tortured bodies lying lifeless on the yellow and white tiled floor I am walking on, torture instruments, lists of victims, belongings, and haunting artwork by Vann Nath, one of the very few survivors who captured the gruesome imprisonment conditions and sheer cruelty of the executioners. As I need to breathe some fresh air, I am standing by the barbwire on the third floor that was preventing victims from committing suicide.

Torn between running away from this horrific place and lingering around to commemorate these victims, I contemplate the city. Phnom Penh pulses with life. Tuk-tuks are honking the horn covering the engines of the thousands of mopeds roaming the city. Cranes are shaping the future of the dynamic capital with new high-rise buildings. The frangipani tree is blooming in the courtyard of S-21 as an homage to the several thousands of victims who were imprisoned and tortured before being slaughtered in the killing fields. As unsettling as it is, visiting Tuol Sleng is a vital step in understanding Cambodia’s past and commemorating those who were lost. It serves as a powerful reminder to learn from history and take responsibility to stand up and speak up against immorality and abuses no matter how small, ensuring that such horrific atrocities remain a part of history and are never repeated.

Reflecting on History:

- The Khmer Rouge regime is believed to have caused the deaths of up to 2 million people—approximately a quarter of Cambodia’s population at the time.

- After the fall of the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot fled to Thailand and remained the head of the Khmer Rouge who were still representing Cambodia and seating at the UN in New York City and receiving international financial aid, while the new Cambodian government was largely ignored.

- The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) is special court that was put in place to prosecute the senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge. At the time of writing, three top leaders had recently been sentenced to life imprisonment.

- As travelers, we strongly believe that we have a duty to try and understand the history of the countries we visit. Understanding history, and its darkest moments, is a way of commemorating victims while keeping a critical mind on our present. At the time of writing, we cannot help but thinking about the alarming events that have been taking place in Syria and bear horrific similarities.

Travel tips:

- If you want to visit S-21, refer to Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

- Many initiatives have been implemented to try and heal the horrors of the Khmer Rouge dictatorship. Some of the most inspiring ones are Phare, the Cambodian Circus in Siem Reap Phare Ponleu Selpak in Battambang that you can attend and support, and Golden Silk that you can learn about.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles and photos (zoom out) about the area!

For more inspiration about Cambodia, click on these pins:

I am in love with your Cambodia related blog sir. Such a heartfelt write up!

This is very sweet of you, thanks again. It would be miss though (and not sir 😉) as we are 2 female travel writers. You may also enjoy the Laos section of the website where we wrote about other initiatives to keep alive traditional weaving techniques. Enjoy! And thanks for the reads!

Oh miss! how bad on my part to miss that 😦

No worries! 😉