Text: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

Photos: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

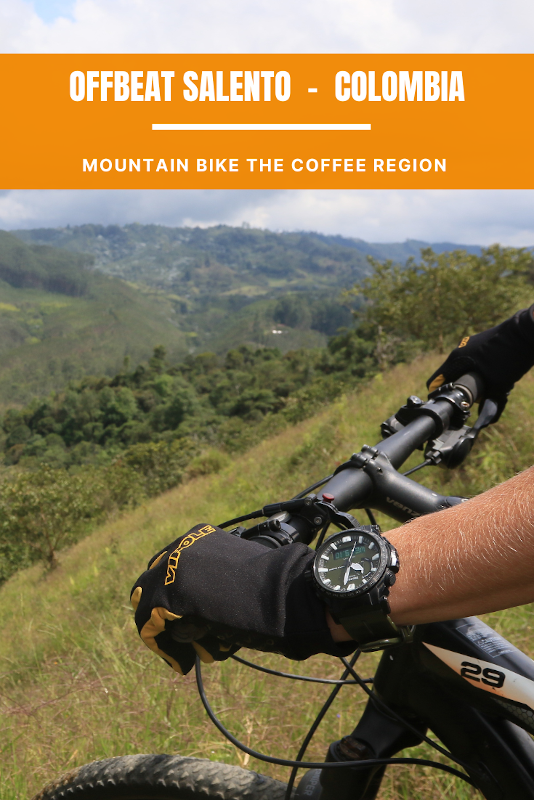

Nestled in the rolling hills of Colombia’s legendary coffee region, the colorful town of Salento has become more than just a postcard stop where visitors enjoy the colorful façades, laid back vibes, quirky coffee shops, viewpoints, and offbeat mountain biking trails. Salento has become the gateway to some of the most astonishing landscapes in the Andes, and one of Colombia’s most beautiful national parks. Most travelers hop into a classic Willy’s Jeep and head up into the Cocora Valley to see the world’s tallest palm trees. While seeing the endangered Quindio Wax Palms, Colombia’s national tree, is worthwhile, beyond the too well-trodden trails lies the wilderness of Los Nevados National Natural Park with its rare ecosystems that only few explore.

Pin it for later!

Early Morning Departure from Salento

Our journey begins early in a simple breakfast nook in Salento, where we check our gear with our guide from Montañas Colombianas. At dawn, we set off on a two-day trek into Los Nevados National Park, a vast protected area in Colombia’s Central Andes, home to forests, páramo grasslands, volcanic peaks, and rapidly disappearing glaciers, making it an essential water reservoir for more than 2 million Colombians living in the area.

Into the Green: Cloud Forests & Wax Palms

The reason for protection is a necessary one. The first hour of hiking takes us along the postcard-perfect wax palms endemic to Colombia and the humid high-altitude cloud forest. It is easy to understand the hype around these trees. Even if the average tree reaches up to 40 meters (131 feet), some specimens reach a dazzling height of 60 meters (197 feet) and form a dramatic landscape as they rise from the grassy mountain slopes.

Indigenous people used to harvest the wax from the trees: a thin protective layer that grows along its trunk. They scraped it to make candles or to use as part of the lost-wax method for metalwork (check out the artefacts of the Gold Museum in Bogota in this article)… The trees were also in demand as building material and irrigation pipes for farmers. In the old days, palm trees here have died by large numbers as their main branches were cut and sold to the Catholic churches each year to celebrate Palm Sunday, a Christian feast during which palm branches are carried in processions.

Now, despite being protected, Colombia’s national tree is on the verge of extinction. Very slow growing and sensitive to deforestation, the sight of the very old and tall wax palms on the grassy slopes of the Cocora Valley may be picturesque; but the reality is that new trees will not grow in the cleared lands around them as they need the shade of the forest. These giants, some of them as old as 200 years are now dying…

The slow Growth of Giants

The slow-growing palms take about 80 years to reach reproductive age and depend on a tiny beetle to pollinate their flowers as there are male and female trees. Once pollinated, fruits are produced and their seed dispersion depends on the rare Yellow-eared parrot and a few rodents. Only this specific parrot nests on the wax palms and is the only one that manages to break open its fruit and swallow it. Passing through its digestive system, the fruit softens and when pooped out can germinate. All in all, only 8 percent of these dispersed seeds germinate and with the land surrounding the mother trees being cleared for cattle grazing and farming over the past decades, young wax saplings stand zero chance of survival as they require at least a decade of shade in order to start developing their roots in a humid soil.

We leave the frantic valley and enter the dense forest following a stream, leaving behind hordes of tourists photographing dying trees going extinct.

The muddy path takes us through a humid forest where wild orchids add touches of colors. Birdsongs betray the presence of blue jays, cinnamon flycatchers, or chacalacas. Mist clings to mossy branches and the path crosses a broken, slippery bridge over a roaring river. The scent of damp earth dominates. No other visitors are to be seen for the next two days, and our guide points out to young wax palm trees near the trail. At this elevation, around 3,000 meters (9,842 feet) still within the cloud forest, the young wax palms thrive in deep shade, and do not even resemble their adult form.

The more we walk up in Los Nevados National Park, the more beautiful the scenery with wide vistas on primary forest on the opposite slopes of the mountains and waterfalls. As we keep gaining altitude, crossing many streams on bridges made of tree trunks, and the air gets significantly cooler, we leave the wax palms behind: we are about to enter yet another endangered and rare ecosystem…

A Night in a Simple Finca

The ecosystems keep changing with the elevation that we gain. Pine trees and eucalyptus have replaced the wax palms. After refueling our ÖKO water filters in one of the many streams, we come across Señor Javier going down to Salento on his horse. He owns a couple of simple farms in the area, including Buenos Aires where we will sleep tonight. Mostly self-sustainable, still, once a week, he takes a day to go down to Salento for the groceries.

At around 3,500 meters (11,485 feet), trees are getting rarer. The 7-leather tree related to queñuales with a similar layered insulation system remain.

After a sustained climb covering roughly 1,900 meters (6,230 feet) of positive elevation along a challenging 9-kilometer-long (5.6 miles) trail, with varying temperature zones, we finally reach Finca Buenos Aires, a rustic cattle farm perched near 4,000 meters (13,120 feet) above sea level. Cows, sheep, horses, pigs roam around along the steep mountain slopes. Here, a local family running Señor Javier’s farm offers us the hospitality and an appreciated snack: a hot agua panela (a drink derived from sugar cane), and a tasting of their own artisanal cheese.

The sun is about to set and the cold kicks in. We gather in the small and simple kitchen and embrace the welcoming warmth of the fire on which a homemade meal is cooking and that we eagerly devour. School is nowhere near, but the two children seem to learn a bit of English with the guests stopping during their trek.

High in the Cordillera Central, nights can plunge well below freezing and we are grateful for the stack of thick woolen blankets as we fall asleep in the clay dwelling.

Exploring the Páramo – High Andean moor

We wake up before sunrise. The fire is not going yet in the kitchens but our guide has been warming up water on the gas stove. The coffee and a quick snack are welcomed before we set off into the night to explore the páramo, one of the most special ecosystems on Earth.

Páramos are high-altitude tropical grasslands generally found between about 3,000 meters (9,840 feet) and 4,500 meters (14,760 feet) above sea level. These unique plants are designed to withstand fierce solar radiation, freezing nights, and intense winds. These fragile grasslands are dominated by rosette plants like frailejones (the paramo’s poster plant), cushion plants, tussock grasses, and a surprising variety of birds, all adapted to the thin air and dramatic temperature swings. Despite the harsh conditions, 252 plant species were recorded in the specific Paramo de Romerales we are discovering.

The páramo is also an ecological key player as it acts like a sponge that captures fog and rain that it uses whenever needed. The excess of water is then slowly released by the plants creating streams turning into large rivers further down. In Colombia, about 70 percent of fresh water comes from forests and paramos that are de facto Colombia’s largest water factories. The emblematic frailejón shrub more specifically plays a crucial role in water storage and regulation. Its hairy silvery leaves capture and retain moisture from the air, and its deep roots store water in the soil, promoting the formation of underground rivers, watering farmlands down below and providing fresh water in the valleys.

Climbing to Pico Chispas

With each step into the Paramo de Romerales, the Nevado del Tolima volcano seems to rise taller as we get a better view of the iconic peak and its glacier. Summiting the 5,276-meter-high volcano (17,310 feet) would require more days and mountaineering gear and is unfortunately not our objective. Tolima is one of the three volcanoes (along Nevado del Ruiz and Nevado de Santa Isabel) that has not lost its glacier yet while Los Nevados National Park used to count six glaciers.

Instead we aim to reach Pico Chispas at roughly 4,400 meters (14,435 feet), a flattish summit that rewards us with one of the best views the park offers of the rolling high plateau, the Otún Lake, the summit of the snow-capped Tolima volcano and Paramillo de Quindío. The frailejónes dot the ridgeline for a spectacular vista.

The air is thin but the sense of solitude and achievement is profound. We are the only ones up here, and the raw Andean landscape that is hard to access makes this views all the more rewarding.

Descent & Return to Salento

The descent back to the farm is quick and we are welcomed by a hearty country breakfast that will keep us going as we have a long downhill ahead of us. Leaving the paramo behind, the temperature climbs back up as we descend through the cloud forest. The familiar wax palms and their elegant silhouettes once again mark the lower reaches of the trail and signal our return into the Cocora Valley. We pass crowds of people queuing to take selfies for a fee at designated spots and are happy we experienced the serene scenery differently and more authentically.

Back in the lively streets of Salento, the rhythm of local cafés and artisan shops feels kind of awkward after two days spent in sweeping wildness and near solitude.

***

There is an irresistible energy to this part of Colombia: vibrant towns perched above emerald valleys, friendly locals, towering palms that seem to touch the clouds, and a hinterland of volcanic giants that make you feel small in the best possible way.

As always, we crave adventures that stray far from the tourist trails. This trek into the Los Nevados National Park delivers, earned with sweat, rewarded with silence, and the rare and pure beauty of vast unspoiled wilderness.

Travel tips:

- If you are craving an authentic adventure that strays away from the tourist trail, then this trek (that can be extended or combined with a volcano summit) into the Los Nevados will be extremely rewarding. A guide is mandatory to enter the park and a necessity. Make sure to reach out to Montañas Colombianas to book your qualified guide and itinerary!

- While similar high-altitude tropical vegetation can be found in Africa and Asia, the Andean páramo of South America is the best known, and Colombia is home to more than 50 percent of the world’s páramos.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

For more in Colombia, click on these images: