Text: Marcella van Alphen

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

At 8,661 feet (2,640 meters) above sea level, Bogotá is the world’s third-highest capital. Framed by the dramatic peaks of the Eastern Andes, the city sits at the crossroads of indigenous heritage, colonial history, and a vibrant urban culture. While many travelers skip Bogotá in favor of touristic Cartagena and its Caribbean beaches, Colombia’s capital is well worth a stop. Here are ten fascinating facts that capture the spirit of Bogotá.

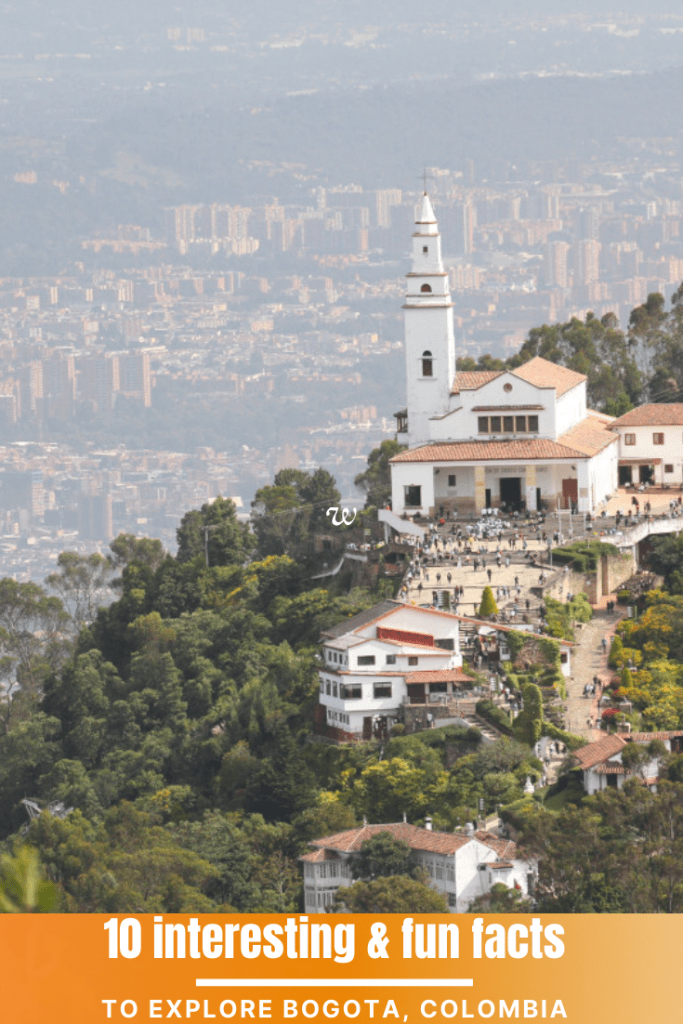

Pin it for later!

1. Bogotá Once Was a Lake

It is hard to picture today, but some 30,000 years ago, the bustling metropolis was a massive lake. The Bogotá River carved a gorge and drained the lake. This geological event left behind a fertile plain of mud and clay where the Muisca people settled and farmed, surrounded by protective mountains they considered sacred.

For sweeping views of the former lake basin, hike or take the cable way up to the famous Monseratte viewpoint, or better, bike up to the slightly higher Lady of Guadalupe who has the advantage of not only towering over the city, but also over Monseratte Hill for the best views. In Muisca times, Guadalupe Hill was called Tchiguachi in their Chibcha language, meaning “Mountain of the Moon”, dedicated to the goddess Huitaca, who embodied sensuality, dance, and arts. In 1538, the hill was renamed after the Virgin of Guadalupe by the Spaniards who planted a cross on its summit before the chapel was erected in 1656: our Lady of Guadalupe was brought from Spain to represent the mountain’s patron saint and installed where it still overlooks Bogotá today at 10,826 feet (3,300 meters) above sea level.

Instead of biking back to the city, adventurous cyclists can continue to El Verjón, a bucolic farming area that shows Bogotá’s rural side and loops back.

2. The Name Comes From Baqatá

Long before the Spaniards arrived, the Muisca people thrived (660 BC-1,550 AC) thanks to good organizational skills and agricultural ingenuity. Masters of agriculture they settled on the high plateau they called Baqatá, which translates as “fertile soil.” Perfect for growing corn, the area sustained their culture for centuries.

Colombia got discovered for the Old World by the conquistador Alonso de Ojeda (1465-1515) in 1493 during Christopher’s Columbus second expedition. When conquistador Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada (1499-1579) reached the region in 1538 in search of El Dorado, he conquered the Muisca and founded today’s Bogotá, also seduced by the fertile land and the absence of malaria-carrying mosquitoes at this elevation. It all started with building the church of Santa Fe, and Baqatá became Santa Fe de Bogotá, shortened into Bogotá overtime. The Spaniards continued to search for El Dorado…

3. Bogotá Has Four Seasons in a Day

Despite being near the equator, Bogotá’s high altitude gives it unpredictable weather. A chilly morning can turn into a sunny late morning, followed by an afternoon downpour and a damp, cool evening. Locals joke that Bogotá has four seasons in a single day—and weather reports are practically useless.

4. Bogotá is The World Capital of Street Art

Bogotá is an open-air gallery with more commissioned street-art than any other city on the planet!

While the graffiti culture in Bogota started in the 1970’s and was later fueled by an opposition to the political situation and repression in the country, a turning point came on August 19, 2011. The tragic death of Diego Felipe Becerra, known as Trípido by his artist name, a 16-year-old teenager who got killed by a policeman while painting a graffiti, and then falsely accused of being a guerrilla fighter, ignited public outrage. The authorities had no choice but to legalize graffiti’s.

Today, Bogotá’s walls burst with color. Throughout the city, some murals convey stories of resistance and hope, others depict exotic birds and wildlife from Colombia, and many are just fun and colorful and brighten up the streets.

5. Bogotá is Latin America’s Cycling Capital

More than in any other Latin American country, Colombians are passionate about cycling, and nowhere is this more evident than in Bogotá!

The city boasts hundreds of miles of bike paths, while Sundays bring the famous Ciclovía, when major roads close to cars and open to cyclists, joggers, and pedestrians, inspiring many cities around the world. A 1974 protest against the dominance of cars in the capital has turned into this weekly pride during which many enjoy a car-free city and a better air quality.

On Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays, riders tackle the steep climb to Guadalupe Hill or head into the Andes for scenic backroads under the watch of the police to keep it all safe.

With heavy traffic and a still-unfinished metro system, cycling is more than just recreation—it’s often the fastest way to get around a city of eight million people (or 11.5 including its metropolitan area).

6. El Dorado Lives On—at the Airport

Bogotá’s international airport, El Dorado, is Latin America’s largest airport in terms of cargo and third largest in terms of passengers. Its name honors the legendary “city of gold” that lured Spanish conquistadors deep into Colombia.

The myth grew from a Muisca coronation ceremony where the new head of state covered in gold dust made offerings to the water goddess from a raft and submerged himself into Lake Guatavita (about 40 miles (60 km) northeast of Bogotá). The Muisca traded on a barter basis without using currency: gold to them was only used as decoration and jewelry as an easy to work and non-corrosive metal. The Spaniards, hungry for gold that was their currency, saw it differently. They believed that if the Muisca could spare gold in a lake, they must have a city of gold hidden somewhere. They first thought Lake Guatavita contained an underwater city of gold. They drained it, or at least they tried! Initially, they used buckets to empty the lake and managed to lower its level by 10 feet (3 meters) after three months. Golden objects were found, but not enough to satiate the Spaniards. Rumors spread and more people started looking for El Dorado “the city of gold”.

In 1735, Charles Marie de La Condamine (1701-1774) a French explorer, naturalist, and mathematician arrived in Quito in Ecuador to precisely measure the distance of one degree of latitude at the equator. The idea behind that scientific mission was to settle on the shape on the Earth. He spent 8 years in South America and mapped the Amazon region after thorough explorations, concluding that El Dorado was a myth. Yet, the Spaniards—and some others—kept looking…

7. Bogotá Houses World’s Largest Pre-Hispanic Gold Collection

With the legendary El Dorado somewhere around the corner and the extensive use of gold by the Muisca people who were talented metalsmiths, the Gold Museum in Bogotá houses world’s most extensive collection of pre-Hispanic gold artifacts with more than 34,000 pieces and over 55,000 pieces if you include pottery, stones, shells and wooded objects.

Highlights include dazzling nose rings, chest plates, idols, and the celebrated Muisca Raft, which illustrates the golden ritual of Lake Guatavita. Beyond its treasures, the museum reveals the extraordinary artistry and innovative techniques of pre-Hispanic goldsmiths.

8. A Capital for Coffee Lovers

Colombia is world-famous for its high-quality specialty coffee. Its climate and terroir are ideal to cultivate the different arabica varieties on its steep slopes. Still mostly handpicked, often grown in shade provided by mango or citrus trees, coffee is very much valued by Colombians themselves.

Bogotá is one of the best places to savor it in one of its many coffee shops offering specialty coffees. Yet, to enjoy your cup to the fullest, Divino Café Especial offers a full coffee experience to learn how to taste coffee, recognize a high-quality coffee and what to pay attention to when buying and brewing. There, you can savor coffee from farm to cup and truly appreciate the passion and hard work from farmer to barista.

9. You May Think you are in the UK, Germany, or Spain While Exploring Bogotá

Bogotá is a melting pot of cultures and it shows in its architectural styles.

On April 9, 1948, Gaitan, a liberal candidate to the presidency was shot dead while walking the 7th street in Bogotá. This triggered the Bogotázo uprising, killing 3,000 in a day and destroying the historic center of Bogotá. Liberals and conservatives continued to fight to death until 1968, a period known in Colombia as “La Violencia”.

Yet, a few Spanish buildings survived the Bogotázo events. One of them is the 1621 Mint House, one of the oldest in La Candelaria. While the gold was systematically moved from Latin America to Europe, mint houses started to be built locally—Potosi, Bogota, Cartagena, etc.—to avoid moving the gold during the long voyage of four to seven months from Cartagena to Cadiz in Spain.

During the Bogotázo events, the director of the Mint House spread concentrated chloride — used to refine the gold and spread it around the building. The vandals rushing to the Mint House gave up as their eyes were burning and they suffocated because of the chemicals saving the building and its occupants who protected themselves with masks. Today’s the Spanish colonial architecture remains, breathing influences from Andalusia with its open patios, arches and fountains—looking out of place here in the humid and cool Bogotá!

In the early 20th century, British architects built an area of red-brick houses, complete with the city’s first indoor toilets. Locals nicknamed it Hyde Park, and it gave Bogotá an English twist.

Germans also arrived, selling coffee roasters and trains, leaving their mark on the city’s industry with their Bauhaus-style homes.

10. Admire Mona Lisa in Bogotá

Medellin-born Fernando Botero (1932-2023) might as well be one of Colombia’s most famous artists. Sculptor and painter, he is well-known for his voluptuous figures and disproportionate scales. Upon his death, he donated his vast collection: 123 of his drawings, watercolors, paintings, and sculptures as well as 85 artworks by famous impressionist artists such as Monet, Renoir, and Picasso to the state—making it the most complete impressionist gallery of South America. Botero himself designed the museography of the Bogotá’s Botero Museum housed in one of the few remaining colonial mansions of La Candeleria neighborhood—the 1734 former archbishop’s palace. The other conditions the Colombian master dictated were that his art would not leave the museum, and would be free for everyone to enjoy—knowing that most of Botero’s majestic artwork are owned by private collectors.

One of his paintings is the Mona Lisa, in a chubby version and the Andean mountains as a backdrop. It is the real Mona Lisa, by Botero!

Around the Botero Museum, in what locals call the cultural block, a few other interesting museums are hosted such as the Mint Museum and the Miguel Urritia Art Museum (MAMU) that showcases work by some Colombian artists as well as the priceless Lechuga-an early 18th-century baroque monstrance made by the Jesuits, composed of 3.5 kg of gold, 1,485 precious stones, including 168 emeralds, 62 amethysts, 28 diamonds, 13 rubies, 1 sapphire and pearls and other gems. Kept in a safe you will have to enter to admire it, it is priceless for its cultural heritage and craftsmanship—an estimate based on the 1985 purchase price by the Banco de la Republica would place it at about 12 million USD.

Bonus Fact: The Only Underground Cathedral Carved from Salt… Is not a Cathedral!

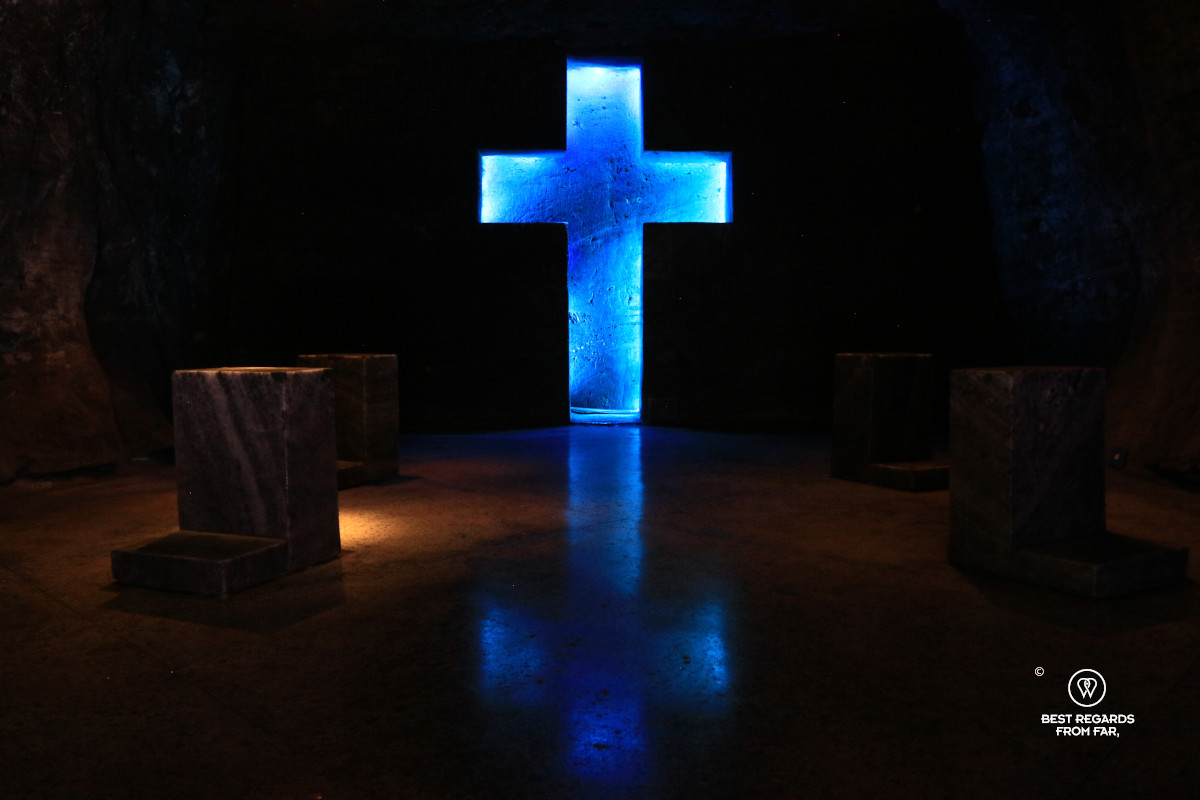

About an hour north of Bogotá, lies an underground cathedral entirely carved out of salt, acclaimed as one of Colombia’s architectural gems.

This vast deposit of halite (rock salt) was formed some 70 million years ago, when an ancient inland sea dried up as the Eastern Andes were rising, leaving behind an enormous underground layer of crystallized salt.

While salt has been a major commodity for over a millennium that allowed the indigenous Muisca people to trade it for metals—mostly absent from this Eastern range of the Andes Mountains—in the 19th century, it started being mined industrially.

Since 1995, 180 meters (590ft) below the top of a grass-covered hill in what used to be an active salt mine, the Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá has ravished its millions of visitors. 250 thousand tons of rock salt were extracted by 127 miners with chisels, sledgehammers, and a pinch of dynamite. They created an expansive subterranean space featuring 14 illuminated Stations of the Cross, each one uniquely sculpted, as well as three naves and a massive central cross—the largest in the world carved from salt, standing at an impressive 16 meters (52 feet) tall.

Despite its name, the Salt Cathedral is not technically a cathedral in the ecclesiastical sense, as it has no resident bishop. The bishop resides above ground in the cathedral of Zipaquirá, and the salt cathedral is nicknamed as such by extension and affection.

Travel tips:

- The best way to explore Bogotá is by bike! Beyond good quality bike rentals, Bogotá Bike Tours proposes city tours, graffiti tours, and demanding outings up in the surrounding mountains and beyond!

- This article is also featured on GPSmyCity. To download this article for offline reading or create a self-guided walking tour to visit the attractions highlighted in this article, go to Walking Tours and Articles in Bogota.

- Divino Café Especial is the ideal spot to thoroughly enjoy a high-quality coffee to your taste. Not sure what your taste is? Signing up for a 2-hour coffee experience will forever change the way you approach a cup of coffee!

- Make sure to visit the Gold Museum.

- The Botero Museum in Bogota is a must-visit.

- Beyond its religious side, the Salt Cathedral has become a major tourist attraction with many businesses such as coffee shops, a spa, and souvenir stores renting space in the underground galleries and attracting hordes of Colombians during weekends.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!