Text: Claire Lessiau

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

We are walking the last kilometers to reach Haeinsa Temple—one of the oldest on the Korean Peninsula—along the river running down the slopes of Mount Gaya, covered in the warm colors of fall foliage. The water makes its way to the valley, jumping in waterfalls, winding between mossy rocks, and polishing slabs, its sound constantly accompanying us.

Pin it for later!

Some votive stones are covered in thousand-year-old inscriptions in Chinese characters or more recent words of wisdom in Hangul, the Korean alphabet. A reclining Buddha among red pine trees indicates the way. The sacred path along the poetic stream leads to three gigantic gates carved in Japanese cedar, each of them preparing us to arrive at the temple, mind aligned with body and protected from evil spirits by their four fearsome guardians.

Since 802, the mountains and the Gaya River have served as a jewel case for the Buddhist temple of Haeinsa, one of the three major Buddhist temples of South Korea.

This UNESCO World Heritage Site shelters a precious treasure. The 500-year-old Hall of Scriptures, accessible only to a few selected scholars and monks, houses 81,258 wooden printing blocks carved with the Korean version of the sacred Buddhist texts, the Tripitaka Koreana. Aiming at repelling foreign invasions with the help of the Buddha, the blocks were destroyed during such an invasion by the Mongols in 1232. It took 16 years to remake them, and the current version was completed in 1251. To prevent any mistakes—and as an act of devotion—three bows to the Buddha were made by the copyist monks before engraving each Chinese character. There are roughly 664 characters on each 70-centimeter-wide and 24-centimeter-long woodblock.

During these 16 years, no fewer than 1.5 million people were involved, from timbering the birch trees to lacquering the woodblocks. Protected by black lacquer, the sacred tablets are stored in two large 500-year-old buildings through which air and light circulate freely. Located at the highest point of the temple complex, where the wind constantly blows to ensure ventilation, the earthen floors of the depository buildings are layered with charcoal, salt, sand, and lime to absorb or diffuse humidity depending on the season. This natural ventilation system has proven more effective in preserving the precious tablets than modern climate-controlled storage facilities.

Only today’s advanced computational fluid dynamics analyses allow us to understand the engineering genius behind this centuries-old jewel case. Beyond the daily temperature gradients in these mountains and the humidity of the forest and its streams, these Korean holy Buddhist scriptures have survived fires, the Mongol and Japanese invasions, and the Korean War during which a US military order was issued to bomb the temple where 1,000 North Korean soldiers were entrenched—it was the disobedience of a Korean colonel who understood the religious and cultural significance of the Tripitaka Koreana, that saved them from destruction.

Today, risks are mitigated with technology such as smoke detectors. In the neighboring Daebirojeon Hall, built to house the oldest wooden statues of Buddha’s in South Korea, dating back to 883, the entire floor would be lowered six meters (18 feet) underground if the smoke detectors were triggered. The national treasures are well protected at Haeinsa.

On the lower terrace, facing layers of mountains fading into the horizon, a life-sized mandala is drawn on the ground in stones and sand, forming a Haeindo. The lines, which seem to interact without ever colliding, are based on a seventh-century poem of 210 characters arranged in 30 lines written by the monk Uisang, the most revered monk of the peninsula. It is believed that walking this mandala while praying grants wishes. We are walking ours, keeping in mind the walking meditation lessons of Monk Jiwol in Naksansa. Starting and ending at the same point, the mandala also symbolizes the unity and singularity of the world. The sunlight is dimmed by the distant trees along a mountain slope. The air already feels cooler, and the setting sun tints the sky with a light purple hue.

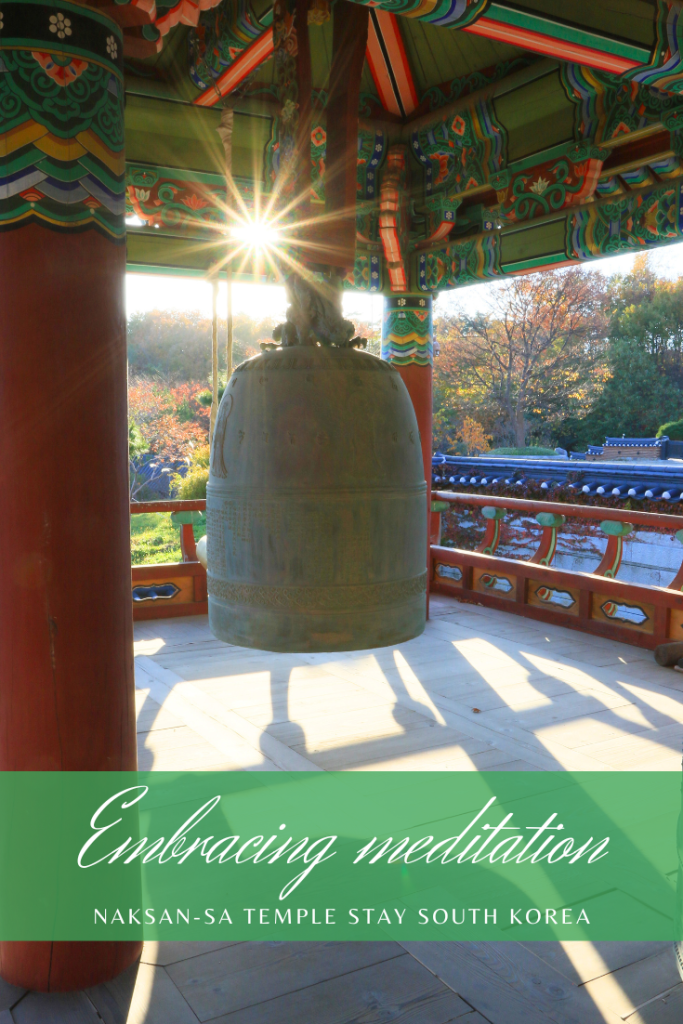

At night, the four dharma instruments resonate in harmony with the massive bronze Dharma bell, or Buddha’s voice, in one of the courtyards. Four of the 120 monks living in Haeinsa call all living things to prayer. The drum, representing Buddha’s teachings, is beaten in a vigorous rhythm to summon land animals. The wooden fish with a dragon head is played for aquatic creatures, and the cloud-shaped gong is struck for those that fly.

In the main prayer hall, dedicated to Vairocana Buddha, who symbolizes the eternal truth and is flanked by bodhisattvas representing wisdom and practice, monks gather to chant the Song of Dharma Nature—an ode to harmony and equality. Their low-pitched voices sing in unison, the sound escaping the temple into the night.

Outside, the temperature has dropped drastically, and the sky is dotted with stars. The fiery fall colors of the forest are now cloaked in darkness. Only a few lights—the shy beams cast on the beautifully painted temples, the glow behind the Wall of the 10,000 Buddha’s, and the thousands of lantern offerings by believers—break the obscurity of the night.

Travel tips:

- The temple stay program started in 2002. There are about 150 temple stays available in South Korea including about two dozen in English where guests experience monastic life and learn about Buddhism including meditation.

- Click this link to book your temple stay at Haeinsa.

- Check out our interactive map for more in the area (black pins lead to an article):

For more in South Korea, click on the images below: