It has been four hours and a half, and my butt has been hurting for more than two hours, as I jump off my rather uncomfortable seat regularly, breathing the diesel fumes! Starting at 5AM, the bus headed out in the night from the island of Flores, Guatemala. After only a few minutes on paved roads, it soon made a turn on an unpaved one that it was to follow for more than four hours… Hardly 100 kilometres: it seemed to be so close on the map… But the long retired US school bus drops off agriculture workers in ranches, stops to wait for locals in tiny villages, halts to let passengers buy meat from a pick-up truck loaded with a cooler crossing our way, makes its way uphill slowly and painfully, and slows down to cross huge muddy puddles… But here we are, at last: I have just seen the sign “Carmelita”!

A soccer field on which black pigs and mules graze, a few grassy streets where chickens roam, some houses clustered among the clearing in the middle of the forest, a former camp behind wooden fences… About 70 families live here today: this is less than half of what it used to be.

As lost as it is in the middle of the subtropical humid forest of Guatemala, about 75km south of the Mexican border, Carmelita used to be a booming town! Founded in the early 19th century, families lived here while their men spent weeks in the forest, harvesting the precious chicle, the sap of the chicozapote tree.

Traditionally chewed by Mexicans to stimulate salivation and relieve thirst, the chicle was discovered in 1866 by North Americans: within 20 years, an industry was born to supply chewing gum, surgical tape or dental supply manufacturers.

This made the good days of Carmelita. The chicle had to be extracted from the trees, then cooked until reaching the appropriate consistency, and put into moulds. Teenage boys headed out to the closest trees, coming back home at night while they were learning the craft. Adults spent up to three months in remote camps of about 50 men. A two-to-three-day trek through the swampy low lands infested by malaria-prone mosquitoes lead them to these temporary settlements. The chicleros had to be strong to endure these conditions: they were mostly Mexicans coming from the surrounding forests and immune to insect bites. The few city guys who tried got back to the city fast!

Chicleros were paid by the pound of chicle harvested. The best ones headed out to the forest in the night, slightly past 3AM. With their very long and razor-sharp machetes, they climbed up the trees and made them bleed: a couple of very strong and precise blows to reach the white gold that would then slowly drip along the bark, all the way down into the bags tied up to their trunks.

They hardly took any breaks: eating makes you too slow and too heavy… Just grabbing a bit of food between two trees, the chicleros worked until they could hardly see anymore, before heading back to camp at night. Days were long and exhausting. But the pay was pretty good: 300 quetzals (40USD) for 25 pounds. A very good chiclero would be able to bring as much as 50 pounds on a good day: 600 quetzals, or enough to buy four mules at that time!

“It was a happy time”, says Ambrosio with nostalgia in his voice. He started when he was 14, and he spent about 20 years as a chiclero. The job was tough and the guys were competitive. He saw several of his friends die of snake bites, or infections after cutting themselves, but still, he misses the atmosphere of the camp and the good pay. At night, they plaid music, danced, joked with the female cook… On good days when supplies and liquors would be brought to the camp by the arrieros with their mules, they could also get drunk!

These were the old times though: in the 80’s the chicle business brutally stopped in Carmelita. The companies hiring these guys all left at once. A chicle of better quality could be found somewhere else. In chewing gums, the natural chicle was replaced by a polymer. Carmelita was not competitive anymore…

Many went back to Mexico while the subtropical humid forest of Central America became at stake: the chicle was a way of protecting it, as the trees were a precious resource.

Some stayed. Today, they log trees in the forest for local handicrafts or for cooking purposes, are arrieros (mule care-takers), cooks or guides.

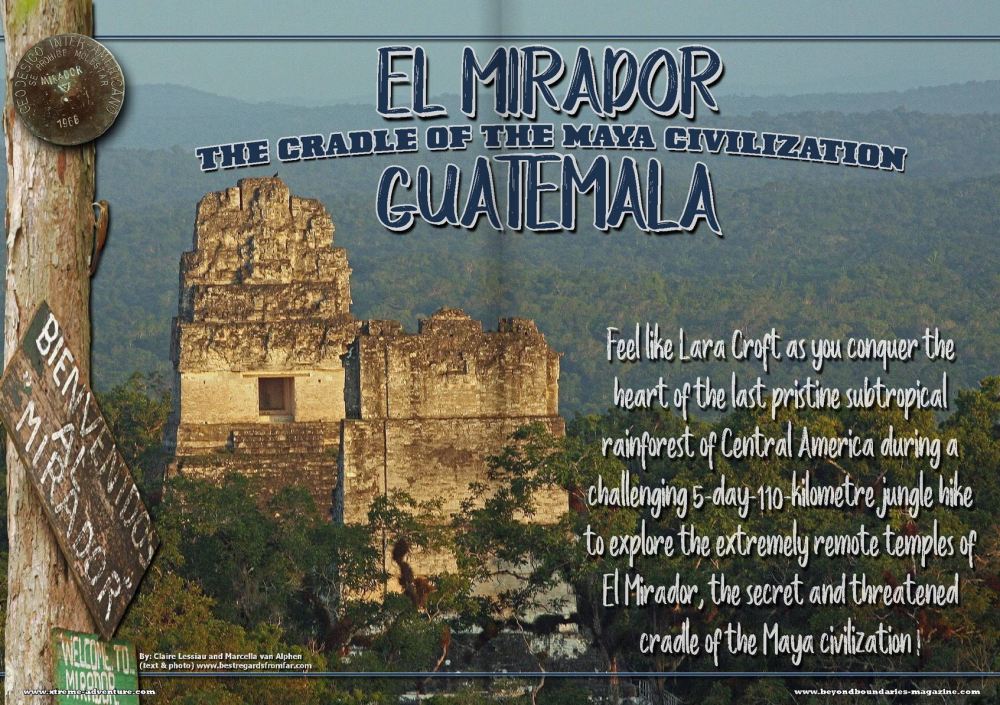

Thanks to ecotourism, and with the development of sustainable and organic food, hopefully the chicle will find its way back into the composition of chewing gums. This would be a way of preserving the forest while developing the local economy to fund the excavation of the great Maya cities we are about to explore: Carmelita is our starting point to discover the cradle of the Maya civilization, the massive city of El Mirador, lost in the tropical humid forest of Guatemala, two days away on foot lead by Ambrosio.

Claire

Travel tips:

- For our complete El Mirador trilogy, refer to the 5-day jungle trek leading to El Mirador and the article about exploring El Mirador.

- To set up your expedition to El Mirador, we strongly recommend the services of La Comision de Turismo Cooperativa Carmelita. The guides are all authorized guides, knowledgeable about the history of the Maya, fauna and flora. Most of them are Spanish-speakers only, but you can request an English-speaking guide. In Flores, many agencies propose this expedition, and we believe spending your money with the community of Carmelita makes more sense. On top of that, they really differentiate themselves thanks to the variety of food and its quality compared to the other groups we have seen – for 5 days, it is greatly appreciable!

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles and photos (zoom out) about the area!!

This article was published in the Beyond Boundaries e-magazine by Xtreme Adventure:

8 Comments Add yours