Text: Marcella van Alphen

Photographs: Marcella van Alphen & Claire Lessiau

Despite Ecuador’s recent spike in political unrest, recurring demonstrations, and the rise of narco-trafficking —with an estimated 70% of South America’s cocaine produced in neighboring countries moving through its ports— there are some pockets of serenity where life unfolds untouched by chaos. One of these places is Chugchilán, a small mountain village nestled on the western slopes of the Western Range of the Ecuadorian Andes Mountains. Here in Chugchilán, a scenic four-hour drive from the capital, Quito, time has stood still: rolling mountains dotted by farms seem to never end. A wide variety of hiking trails crisscross the landscape making this area a hiker’s paradise. At 3,200 meters (10,500 feet) the air is thin, the elements strong, and the views endless: the stage is set for some of Ecuador’s most rewarding hikes…

Pin it for later!

Hiking to the Quilotoa Crater Lake

From Chugchilán, the path to Lake Quilotoa winds through terraced fields and quiet hamlets. I feel the powerful rays of the sun on my skin at this altitude when they pierce through a thin layer of mist that rises from the valley right after sunrise, revealing the green canyon below. It is mid-October and as the rainy season has already kicked in, an early departure is key to try and avoid the afternoon rain.

The hiking trail passes through a patchwork of small plots of farmland. Friendly women in colorful traditional clothes tend to their barley, potatoes, broad beans, corn, squash and lupines—one of the Andean super-food easily recognizable by its beautiful purple flowers. Permaculture has been a tradition here for centuries: agricultural knowledge has been passed down through generations and farmers have learnt to leverage their fields in the best possible ways. Lupines enrich the soil by fixing nitrogen and grow next to the nitrogen-hungry corn, cleverly avoiding the need for fertilizers that remain unaffordable to most. Potatoes are planted as a rotation crop to increase soil aeration, thriving in the cold nights in the mountains. Beans climb along the cornstalk and stabilize the maize in high winds while the wide leaves of the squash plant keep the soil moist and prevent weeds. Poly-culture rules, a natural barrier to pests and plagues, and haven for birds and butterflies.

As the trail ascends, hummingbirds flash through the shrubs, thrushes forage for food in the soil while overhead, American kestrels and Andean hawks effortlessly glide on the thermals while scanning for prey. I cross fresh water streams and sandy white cliffs, my heart racing to keep a steady pace, eager to witness the beauty of the mythical lake before clouds cover it up.

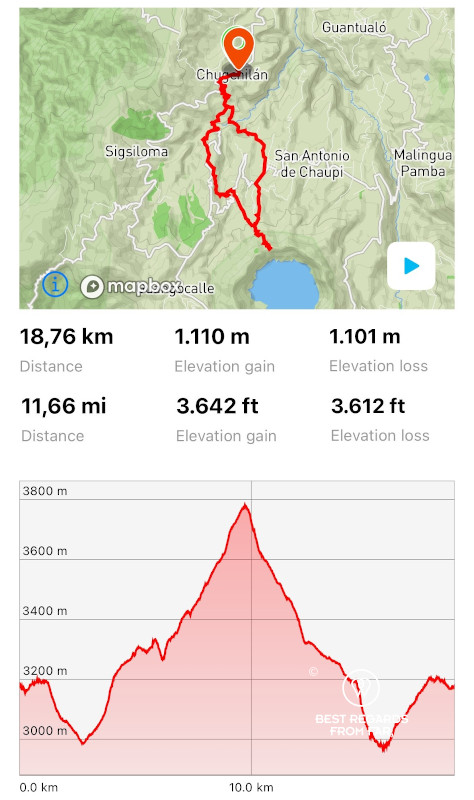

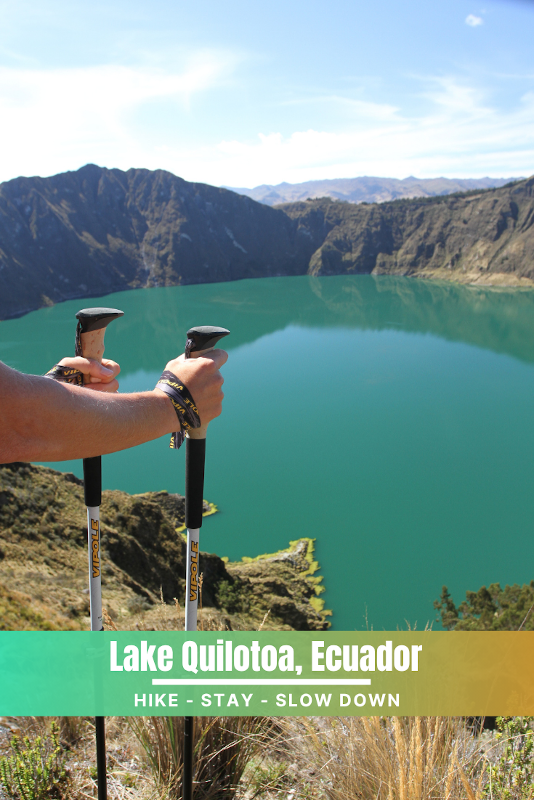

The path is easy to follow, and a quick check on the 3D map on my iPhone allows me to check my progress and anticipate the upcoming challenges. I climb past donkeys and alert farm dogs. A few villagers rush down as walking is often a better option than waiting for the slow and not-so-frequent bus. Some indigenous women wearing traditional clothing and cheap plastic sandals speed walk the steep and narrow trails with ease as I try to conquer them with my sturdy hiking boots. Soon, I am facing a slope: the rim of the crater lake. The weather is clear and the first clouds are tickling the double summit of the Illiniza Volcano. I speed up to the edge of the rim. Then, suddenly, the vista opens on the breathtaking Quilotoa Crater Lake!

800 years ago, during a massive volcanic eruption, the magma chamber of the Quilotoa Volcano emptied completely, collapsing its summit, and forming a considerable crater of about 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) in diameter and 800 meters (2,600 feet) deep. The lake’s turquoise waters shift slightly in hue as I point my camera lens on it from different angles. When the wind ripples across its surface, dark shapes rise from its depths, crossing a part of the lake before dissolving as fast as they appeared. Mineral-rich gases, especially carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, bubble upward, a reminder that this serene lake is very much alive.

A Taste of the Andes at an Artisanal Cheese Factory

While hiking from Chugchilán to Lake Quilotoa is one of the most popular hikes of Ecuador, a wide variety of hiking trails offer different atmospheres and views on the surrounding valleys. From above the Black Sheep Inn, a winding dirt road leads to the community of Chinalo Alto, where locals focus on artisanal cheese-making at the Quilotoa cheese factory. The dirt road follows a ridgeline, and winds past hamlets with expansive views on various valleys dotted by small farms. Along it, dogs, cows, donkeys, horses, pigs, sheep, goats, roosters, and an unusual lama stare at me with curiosity as I walk to the rhythm of my hiking poles.

Back in 1978, a Swiss project aimed at developing a cheese factory to provide a livelihood to local families. Almost 50 years later, the cheese factory is thriving, supplying local hotels and guesthouses, restaurants and local markets. The Swiss-cheese making tradition was transferred to local farmers and today, about 60 families sell their milk to the cooperative.

As I step inside the queseria, I am welcomed by Agosto, a cheerful cheese maker stirring a yellowish liquid (the whey) in which coagulated lumps (the curds) float in a large vat. As I get closer, I notice he is cutting the curds to help release the whey. The truck has just left to deliver the weekly production of Andean, mozzarella-style and local Emmental cheese to the market of Latacunga, and almost all his cheese is gone! He proudly shows me the facility during an informal visit and keeps apologizing for the lack of stock. Back at the vat, he is about to wash the curds, replacing some of the whey with water. “Washed curd cheeses tend to be more elastic and have a nice, mild flavor,” Agosto explains in Spanish. Before he starts, he grabs a mug and pours some of the whey for me to taste.

Luckily, the Black Sheep Inn is on the route of the delivery truck! That same night, I taste the local mozzarella, the best-seller of the cheese factory on a delicious stuffed eggplant.

Enjoying the Award-Winning Black Sheep Inn Ecolodge

A bit more than a handful of guesthouses are available in Chugchilán, including the Black Sheep Inn, a pioneer of eco-tourism in Ecuador and a legend along the Quilotoa Trail—taking through hikers from Sigchos to the crater lake over two days. Founded in 1994 by US travelers Michelle and Andrés who simply fell in love with the area, the inn began as an experiment in sustainable living long before “eco” became popular. Today, the Black Sheep Inn is locally-owned and run, and it has become an award-winning model of responsible tourism: a community-run lodge powered by ecological principles, a vegetarian cuisine, and built with up-cycled materials while providing great comfort.

The Black Sheep Inn is of these places when upon arriving, it already feels like time will be too short. Its expansive views on the Andes, its challenging terrain of frisbee golf with lamas and alpacas, and its artisanal gym ravish the most active guests. In its cozy interior, large hiking maps of the region adorn the walls, books and boar games are best enjoyed with a warm cup of local coffee and homemade slice of cake, while the fireplace casts its soft light on the locally-made craft decorations.

The nights can be cold, and the wood-fired sauna is soothing after a day hiking at altitude. Bringing in a few fresh branches of eucalyptus picked along the trail, I enjoy the heat while I throw some ladles of water on the volcanic stones spat out by Quilotoa centuries ago and that are now distributing the heat in the large sauna.

Beyond hospitality, the Black Sheep Inn channels its profits into scholarships, local schools, and environmental programs, proving that tourism can enrich a community without eroding its soul. The true home away from home is hard to leave as many more hiking trails lie around the corner to be explored!

Proof of Ecuador’s Potential

Leaving Chugchilán, it is hard not to feel both gratitude and melancholy. Gratitude for having witnessed such an authentic and tranquil place where local people live simply but with laughter, pride, and generosity. Melancholy because villages like this still bear the consequences of a country strained by unrest far from these mountains.

It is a shame that communities so rich in culture, tradition, and natural beauty must endure the ripple effects of Ecuador’s instability from power struggles between the government and indigenous communities, to the unsafety brought by drug transport along the coast, triggering everything from petty theft to kidnappings and lethal shootings. For travelers, Chugchilán is proof of the country’s immense potential: a place and community that thrive through sustainable tourism.

Travel tips:

- To explore Chugchilán, the hiking trails, and the Quilotoa Crater Lake make sure to stay at the award-winning Black Sheep Inn Ecolodge, and add a few more days than what you initially planned for!

- For planning hikes and tracking, the Whympr app with its 3D maps is ideal.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

Hi you two! Are you currently

Hello, Sorry but your comment got cut off. Can’t read it. You can email us at bestregardsfromfar@gmail.com. Thanks!

I love crater lakes! This sounds beautiful!HRSent from my iPhone

Thanks Heather!! Yes Ecuador was a bit sporty, but this are was so worth it!