Text: Claire Lessiau

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

Tourists used to flock to Malaga chasing the sun and Mediterranean Sea along the Costa del Sol, to the point that this mass tourism led to an overbuilt coastline. But the sun-drenched city—actually the 9th city in the world with the most hours of sunshine a day—managed to reinvent itself, highlighting its history, culture, and gastronomy. Today, beyond the relaxing beachfront where sardines are grilled in chiringuitos restaurants, the shaded narrow alleys of Malaga twist around old walls leading the curious traveler to the gems of an authentic city waiting to be rediscovered.

Pin it for later!

Peeling Off the Layers of Malaga’s Historic Heart

The compact historic heart of Malaga reveals layers of civilizations and a rich multicultural history that are easy to explore in a relatively short amount of time.

The 11th-century Alcazaba fortress dominates Malaga’s old town. Built by the Nasrids—who would later erect the Alhambra in Granada—it once protected a kasbah, or fortified city, with its palaces, gardens, and towers. At its base lie the much older ruins of a Roman amphitheater, which marble blocks were later upcycled by the Moors to embellish their own palaces. Nearby, the fish salting place used to stand or “malaka” in Greek that gave its name to the city founded by the Phoenicians around 800 BC.

A few blocks away the Cathedral of Malaga stands. When the city fell to Catholic forces in 1487 after almost 750 years of Moorish domination, all the mosques were replaced by churches. A mosque used to stand at this corner where the grand, imposing, and unfinished cathedral now dominates the historic district. While it took more than two centuries to be built—starting in 1528—the construction was halted in 1782, leaving it asymmetric with just one tower and a roofless flank. Locals still affectionately call it La Manquita—the one-armed lady.

Picasso, the Boy from Malaga & One of World’s Most famous Painters

Victim of mass tourism centered on the sun and the beach, the city of Malaga succeeded in converting itself into a cultural destination thanks to the opening of one museum: the Picasso Museum. Opened in 2003 in a 16th-century Andalusian palace in the pedestrian alleys of historic Malaga, it showcases intimate art pieces of the world-famous Malaga-born painter. The success has been such that today, it is the most visited museum in Andalusia and definitely a not-to-miss site in the city!

On 25 October 1881, Pablo Ruiz Picasso was born in a modest house on Plaza de la Merced, only a short stroll away from the Picasso Museum. Today, his bronze statue sits on a bench in front of the traditional building on the grand square. His mother came from a family rooted in Malaga’s thriving wine industry; his father was a painter and professor. As the local wine economy collapsed with the phylloxera that hit the region of Malaga in 1878, the family moved away, but Picasso returned every summer until he was 18, and enjoyed the scenes of the high society of Malaga.

While he preferred to keep his mother’s Italian maiden name that sounded more exotic than “Ruiz”, he had kept the city in his bones. Malaga offered him four muses that he would honor in his art pieces: women, bullfighting, the Mediterranean Sea, and doves. By paying attention, his women are recognizable in many of his works. There is Olga, the poised Russian ballet dancer; Marie-Thérèse, the calm 17-year-old swimmer with a perfect athletic body and recognizable nose; Dora Maar, the eternally weeping muse of Guernica; Françoise Gilot, the strong “woman flower” as he nicknamed her, mother of two of his children; and Jacqueline Roque, often shown with her big eyes.

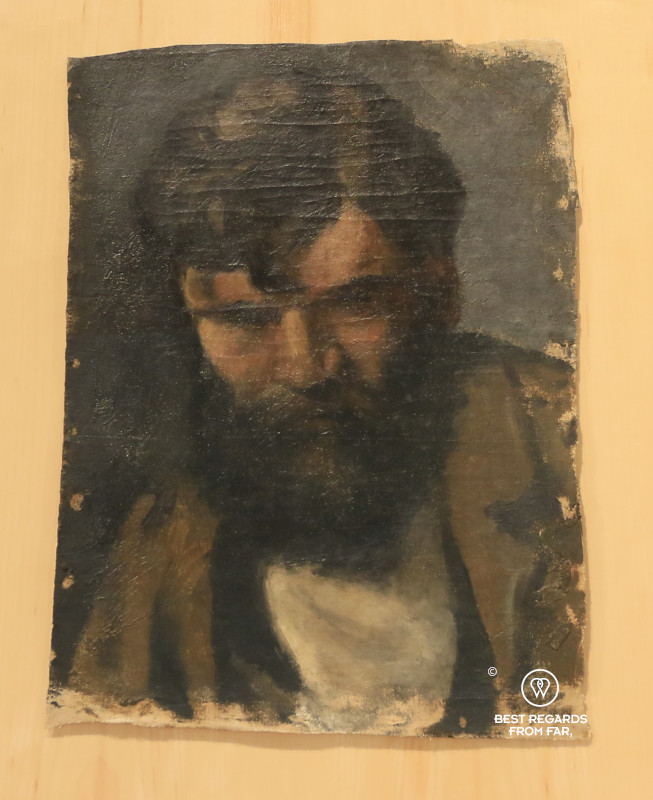

In Malaga, it is not only his evolution as a painter that is showcased, but the contrasts between his young years and his last years. The art pieces come from the private collection of the first son of Pablo Picasso who donated it, comprising many unsigned painting that Pablo intended for his family, intimate early sketches, and Cubist research. It is not the most famous paintings by Picasso that are hung to the walls, but a more tender side of the artist.

While several Picasso Museums honor the artist—Barcelona where he spent his formative years, and Paris the capital of the country where he spent most of his life—the Picasso Museum in Malaga is very intimate, the ideal jewel case for the works of a painter who gave only three interviews in his lifetime and never titled any of his works.

A Taste of Andalusia: Markets, Tapas & Secrets of the Kitchen

At Atarazanas Market, a 14th century marble arch stands tall. It is the last surviving remnant of the Nasrid shipyard that once overlooked the sea in the commercial and military harbor. Today, the Mediterranean has retreated as land has been reclaimed, and the market bustles inland. Under the stained-glass windows that depict scenes of Malaga’s maritime and daily life, locals and tourists browse the fish, meat, and vegetable sections.

The local tapas are appealing: our guide and foodie enthusiast Javier with Spain Food Sherpas goes from a stall to another, marveling at the freshness of the dishes. The anchovies that have given their nicknames to the inhabitants of Malaga—boquerones—are the most popular snack around, preferably pickled (soaked in vinegar for 24 hours then salted and put in olive oil). Octopus salad also sells fast, especially in the summer. Meat dishes are also mouthwatering: Javier presents the popular pork-based favorites: carrillada is a dish made of the very tender pork cheeks often in a stew with red wine and veggies, and in Malaga, the Moorish influences come through as the pork is simmered with almond and raisins instead—and a splash of muscatel. The Malaga-style meatballs are also served with almond sauce as they grow locally, after the tree was imported centuries ago by the Arabs.

Yet, we are not at the market to indulge in some local tapas, but to gather the freshest ingredients to cook them ourselves—with the invaluable help of Chef Pepo in the professional kitchen of Kulinarea.

Our cooking class begins with premium olive oil tasting, a staple condiment around the Mediterranean Sea. “These oils are not for cooking,” Chef Pepo warns. The precious elixirs are of course extra virgin olive oils—meaning first press and cold press without any added chemicals. Some are pure such as the hojiblanca Blanca (white leave) from Jaen with its intense color, spicy kick and strong character, or the picual arbequina, originally grown in Catalonia that is lighter in color and less spicy. Others such as the one produced in the white Andalusian village of Monda are blends.

Later, as we prepare all together a pork tenderloin with muscatel sweet wine sauce, garlic prawns, tortilla, roasted noodles, and churros for our feast to come, Chef Pepo is not only keeping an eye on every step ensuring his instructions are properly followed, but also dives into the local culinary culture, providing a wealth of information. With humor, he also details how to avoid the worst restaurants in Spain, designed for tourists, simply by running away from the pitchers of sangria! Spaniards do not drink sangria when they go out. It is a drink that is prepared at home, now and then. “When you see a picture of a jug of sangria next to a paella, you can be sure that you should run away from this restaurant,” Chef Pepo exclaims. “It is only to attract tourists!” This makes a cooking class the only proper place in Spain where to enjoy a sangria!

Wine, Lost & Found: The Vines That Came Back from the Dead

Strong of a 3,000-year old history started by the Phoenicians, the wines of Malaga used to reach international fame. Montes de Malaga and Sierras de Malaga close to Ronda were famous areas for both white and red wines. But in 1878, the phylloxera pest disembarked from ships coming from America in Malaga’s harbor. These tiny sap-sucking insects feeding on the roots and leaves of grapevines rapidly spread across the continent. Vines died fast. Wine production plummeted. Trade collapsed.

Originating in North America, the vines there developed a resistance that the local vines did not possess. It is only intensive research that has stopped the plague and saved the European wine industry: grafting a scion on a resistant native American rootstock allowed to conserve the characteristic of the scion while resisting the phylloxera. The industry was slowly revived, and the region continues to be known for its sweet Moscatel and Pedro Ximenes wines while boutique bodegas dot the hills of the Montes de Málaga and Sierras de Málaga, producing bold reds and crisp whites.

***

While the beaches and inland white-washed villages of Andalusia are definitely worth the visit, it would be a shame to rush through Malaga. The sunny city will seduce art lovers, foodies, and history buffs as long as they venture into the narrow alleys of the close to 3,000-year old harbor.

Travel tips:

- You can book tours with professional guides at the Tourist Office of Malaga.

- For your cooking class, reach out to Spain Food Sherpas.

- Make sure to book your ticket to the popular Picasso Museum.

- To go around, D Bike Rental Malaga offers reliable scooters with an excellent pick-up and drop-off service.

- This article is also featured on GPSmyCity. To download this article for offline reading or create a self-guided walking tour to visit the attractions highlighted in this article, go to Walking Tours and Articles in Malaga.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!