Text: Claire Lessiau

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

For most visitors, Granada begins and ends with the Alhambra, where carved stones speak in calligraphic verses, and the water displays of the peaceful fountains reply—a quiet dialogue under the orange blossoms of its Garden of Eden.

But step beyond its adorned walls, enchanting gardens, and refreshing fountains, and you will find a city still whispering secrets. Here, water flows silently under your feet, you can bathe like the Nasrid nobility once did, and let each tapa tell its own story of mixed cultures, hardships, and unique flavors.

Pin it for later!

1. Water: Granada’s Silent Architect [The Alhambra]

Granada’s foundation is not stone or mortar, but water. Water is what makes the Alhambra and the enchanting gardens of the Generalife possible, and it is omnipresent on the hill of the most famous monument of Islamic architecture in the West.

This has not always been the case. Prior to the arrival of the Muslims, the Sabica Hill where the Alhambra now proudly dominates Granada, just hosted the ruins of an old Roman fortress—where today’s Alcazaba stands—as there was no water, and the city had developed on the opposite hills.

Today, the Alhambra’s delicate fountains and mirrored ponds are just the visible face of a sophisticated hydraulic system developed by the Nasrids over 700 years ago. An ancient canal still brings water down from the Sierra Nevada to the Alhambra and its gardens: the Nasrids engineered an aqueduct from the Rio Darro, 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) upstream, to bring water to the Generalife gardens and the fortified city of the Alhambra. It is not only the length of the canal that impresses. The river flows more than 100 meters (328ft) below the Alhambra: a small dam feeds the canal that follows a gentle slope to the Generalife. A noria (waterwheel) was used to pump up the water 125 vertical meters (410ft). Also, a water hammer effect was used to pressurize the water flow to push it even higher into cisterns and fountains throughout the fortress. From there, pressurized water distribution enabled flowing fountains, mist-cooled gardens, and running water throughout the hilltop palace and the city. This was simply an unequaled marvel of hydraulic engineering, and remained so for centuries at a time when much larger cities relied on basic aqueducts or buckets!

More than comfort, water here means power, pleasure, and peace.

Even today, in the Albaicin, Granada’s old Moorish neighborhood, if you pause on a quiet stairway, you may still hear the murmur of the ancient irrigation channels that wind between houses, nourish citrus trees, and sustain the private gardens of the Carmenes, hidden behind thick walls.

Once the crowds shuffle out of the Nasrid Palaces of the Alhambra, and the golden light begins to fade behind the Sierra Nevada, a different Granada emerges…

2. The Albaicin neighborhood: Granada’s First Line of Defense

Down the Sabica Hill of the Alhambra, step into the maze of the Albaicin. The Moorish district is a labyrinth of chaotic steep cobbled alleys that were designed for defense—narrow enough to trap cavalry, high enough to see invasions coming.

Plaza Larga is the best place to feel the pulse of Albaicin. On market mornings, older residents roam through the fruit stalls. Local kids chase pigeons. Cisterns hide in corners. In the background, the Alhambra watches silently from across the valley of the Rio Darro. From here, the impressive ramparts of the fortress hide the sumptuous palaces and delicate architecture of the utmost refinement, and the snow-capped peaks of the Sierra Nevada make for a dramatic backdrop.

Feeling the Albaicin is zigzagging through whitewashed alleys where bougainvillea lean in from every corner, looking for the pomegranate symbols (“granada” in Spanish) that are carved into rain gutters, drawn on street signs, and painted onto doors, and arriving at the mirador de San Nicolás. The popular viewpoint on the Moorish fortress gets very busy at sunset, and thankfully there are some more intimate options not known by the crowds…

Back in the city center, the Alcaicería (silk market) still retains the layout of its Islamic past: the streets were rebuilt as narrow as they used to, providing shade today to the tourists browsing through the souvenir stores. For centuries, silk was Granada’s lifeblood: the city produced up to 3 million kilograms (6.6 million pounds) a year, with two-thirds of the population involved in its cultivation, weaving, and trade. The Alcaicería was once a bustling hub with over 2,000 shops dedicated to silk before the Reconquista.

3. The Arab Baths Are Back!

Booed by the Catholics after the Reconquista, and even forbidden during the dark times of the Inquisition, the tradition of Arab baths vanished from Granada for centuries. What was once a cornerstone of daily life—ritual, hygiene, and social gathering—was condemned as incompatible with the new religious and cultural order.

Today, however, the hammam tradition has made a return to the city where Arab baths were omnipresent. At the Hammam Palacio Nazarí, echoes of that past are gently revived as a luxury interpretation, marrying historical inspiration with modern wellness. Inspired by the original layout of the bathhouses, the space invites visitors to move between the cold frigidarium and hot caldarium pools beneath elegant arches and dimmed light. The scent of essential oils used by the masseurs, the fragrance of spiced tea enjoyed between treatments, and the timeless atmosphere create a relaxing haven that seems far removed from the fast pace of modern life.

4. Tapas Time: More than Food, a Cultural Tale

The tapas tradition is strong in Spain, and Granada is the last Spanish city where tapas still come free with your drink. The town filled with students from some of the best universities of the region is lively at night and a long queue often indicates the best tapas hang outs. No sangria there—the drink is reserved for tourists who still think this is a Spanish tradition when one goes out—but the popular and refreshing tinto de verano (a mix of red wine with soda and ice cubes), a cold draught beer or its even more refreshing version as clara limón (beer with lemon soda), a vermouth (aromatic fortified wine infused with a blend of herbs, spices, and botanicals, and served with an olive or slice of orange), or a red wine sits on tables. Busy waiters rush around putting down a variety of tapas with nonchalance.

In some places, they come according to a set order, and it may take 5 or 6 drinks to taste a good array of bites. In others, specific tapas can be ordered from a list. The most popular ones are migas—breadcrumbs fried in olive oil with peppers and pork that speak to poverty and ingenuity—and fried eggplant with molasses evoking Jewish kitchens.

For more refinement, a tapas tour through the heart of the city is a great bet. Molly, our foodie guide with Spain Food Sherpas, takes us to Alameda, a sleek modern and high-end wine bar recommended by Michelin. First up: a glass of Albariño from Galicia. “It is like biting into a crisp apple,” Molly smiles. The white wine matches perfectly with quisquilla, a local prawn only found near Granada’s coast and beloved by Granadinos. More surprisingly, the Albariño also pairs fantastically with a croqueta de rabo de toro, or ox tail croquettes—crispy on the outside and irresistibly creamy within, filled with a slow-cooked ox tail. The Roman influence of the gladiator games has left an imprint today in Andalusia with bullfighting, and butchers around the bullring still make the most of every cut.

Croquettes were a way to stretch scraps in hard times in very agricultural Andalusia where food was directly related to the abundance of the harvests. The poorest region of Spain, Andalusia has not had an easy past. As such, Andalusian food is survival food, and many of today’s favorites have been poor man’s dishes, such as the fennel which shoots are eaten to leave the bulb intact for a later day, the hearty pumpkin purée and the migas.

Nothing sums up the roots of Granada better than sitting at a table at Casa Castañeda with a Mosarab chicken (“Mosarab” refers to Andalusian and northern African fusion) served with couscous next to a fragrant spinach with chickpeas and paprika, cooked with aromatic spices and goat cheese, all accompanied by a glass of red wine from the Ribera del Duero area—one of the most prestigious wine regions, slightly north of Madrid. Moorish, Jewish, and Catholic traditions at the same table.

To finish on a sweet note, the energy bar of the Muslims, turron does the trick! Either hard or soft, mostly based on almonds—which trees were introduced in Andalusia by the Arabs, as well as pomegranate and bitter orange trees, rice, sugar cane (that the Spaniards then took to the Americas)—other ingredients include eggs, honey, sugar and oil for the soft version. Reminiscent of it, the Tears of Boabdil is a pie of caramelized almonds in butter and honey with raspberry sauce on top, a sweet homage to the last Nazrid ruler of Al Andalus.

Another decadent option is a multiple-award winning Pedro Ximénez wine—a naturally sweet dessert wine created with at least 85 percent of Pedro Ximénez grapes, picked very ripe and dried in the sun to concentrate–with hints of dried plums and dates that highlights the power of the sun and excellent wine making; or even better, a Victoria Nº2 Moscatel Dulce by Jorge Ordonez, made of the best raisins around Malaga and its delicate melon taste.

5. Iberian Ham: A Crash Course in Flavors

Surprisingly, the moscatel pairs perfectly with the top of the line of Spanish cured hams, the jamón Ibérico de bellota…

At another stop, cured hams hang from the ceiling. Paying closer attention, a colored-label around the hoof of the pig indicates its quality and what it had been fed on. Molly explains: the black-label is for the best of the best, the jamón 100% ibérico de bellota, also referred to as pata negra, produced from pure-bred Iberian pigs that roam freely and only eat acorns. The other labels are for hams from pigs that are not pure-bred but at a minimum 50 percent ibérico pig breed. The red-label indicates these free-range pigs. The green label is for pigs that are pastured and fed a combination of acorns and grain while the white label is for pigs that are fed only grain. In all cases, the ham is cured for 24 months.

The diet of acorns of the black-footed pigs of the black Iberian breed leading to jamón Ibérico de bellota contributes to its amazing taste and health benefits: rich in antioxidants, oleic acid (similar to olive oil) and polyphenols, these hams do not contain saturated fat. “Free-range meat is much healthier as saturated fat is a consequence of being fed with grains,” Molly explains, as we are enjoying tasteful chorizo and lomo of the same quality.

Looking closely at the color of the fat in our plate, Molly compares a Serrano ham—that comes from pink pigs fed on grains, the everyman’s product—to the portion of pata negra: the latter is a bit golden (the more golden the more acorns) while the fat of the serrano ham is mostly white. Yet, a connoisseur, Molly has us taste the best part of the serrano ham: hanging for years from the foot, all the flavors leak into the tip!

“Eat the ham, save the land,” Molly jokes, explaining that the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve where the black Iberian pigs live close to the border with Portugal supports a traditional, sustainable ecosystem.

6. Sacromonte: Troglodytes & Flamenco in the Caves of Granada

Beyond the whitewashed alleys of the Albaicin, further up along the banks of the Río Darro, Sacromonte rises along the hillside. For centuries, it was home to the city’s outcasts: when the Muslims were expelled after the Reconquista, many found refuge here. They were soon joined by the Roma (or gitanos), who had entered Granada with the Catholic king. Lacking resources, the gypsies dug into the soft hillsides to build troglodyte homes that offered protection from both the summer heat and the biting winter cold.

After being rediscovered by Irving in the 19th century, the Alhambra appealed to romantic writers and travelers. While locals would express their heartbreaks and hardships through flamenco, after the Second World War, some tourists witnessed some performances in the Sacromonte area. They threw a few dollars—vast amounts of money for the gypsies of the time. Kids would keep an eye out, and when seeing tourists come around the corner, the singing and dancing would start, to the point that it was thought the gypsies were only singing and dancing all day!

Today, the flamenco shows have professionalized but remain raw and intimate in the troglodyte venues of Sacromonte, towered by quiet view points on the Alhambra. Yet, the district is changing. Agave and cactus once planted to stabilize its fragile soil are more important than ever as the hill has been drilled extensively and erratically for housing. However, the foundations of the community are shaken as caves are turned into sought-after and expensive Airbnb’s.

7. Power Faded, yet Poetry Remained [Back to the Alhambra]

While tourists try to get a front row spot at the mirador de San Nicolás or a seat in one of the troglodyte venues to attend a flamenco show, we stand at the quiet mirador de la Vereda de Enmedio in Sacromonte, simply taking in the last sunrays as they taint the red Alhambra—color that gave its name to the landmark—in slightly warmer hues.

Even with its enduring grace, the Alhambra was never meant to last. When Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar—a sultan like many at the time—arrived in Granada in 1237, he knew Al-Andalus was meant to end. After five centuries of prevalence, the caliphate had been under pressure from the Aragon and Castile catholic monarchs. The constructions of the Alhambra were not meant to defy time, but to enjoy life in its utmost refinement while keeping a defensive purpose. The Nasrid dynasty that he founded would shape this hilltop fortress for 254 years. His successors added their own touch, raising palaces out of humble plaster and brick, carving verses of devotion into stone, and channeling mountain waters into mirrored pools.

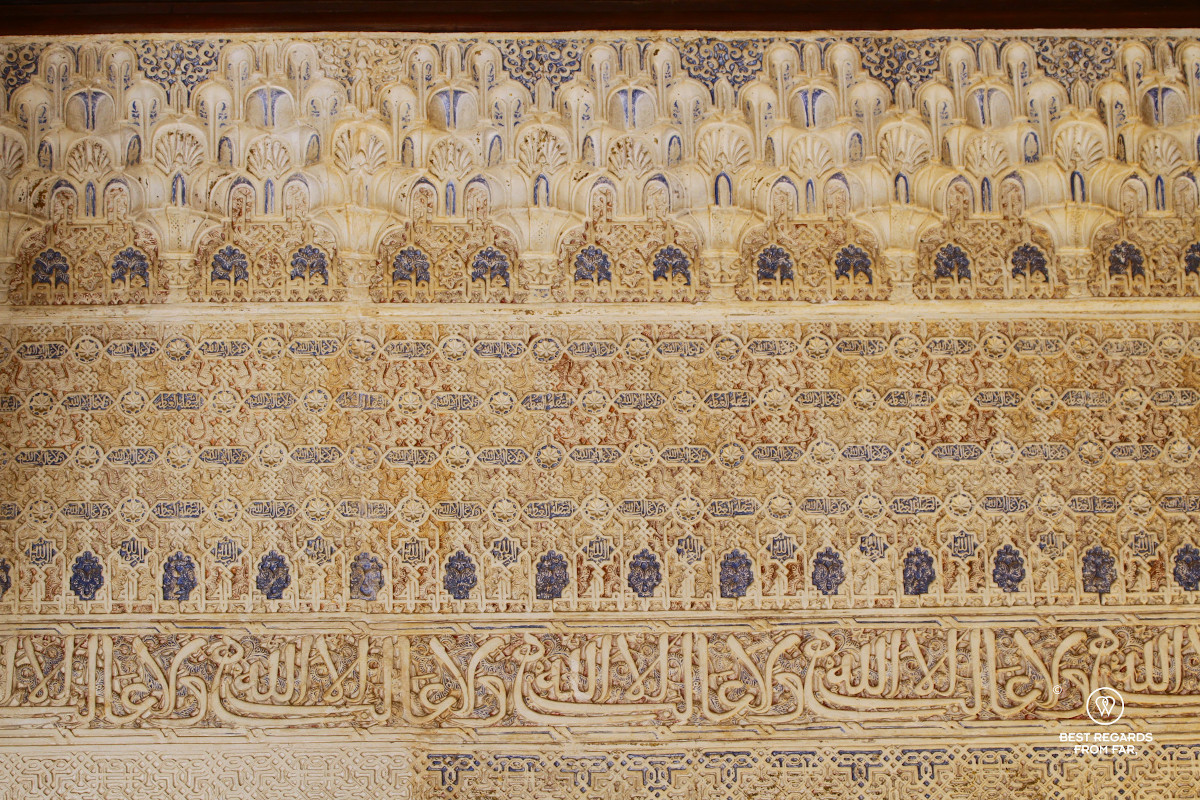

While simple local materials (compressed stones for the structures covered by plaster for the decorations) were used to build the palaces of the Alhambra, quickly and for cheap, the utmost attention was paid to the elegance of the decor. Sciences and arts intertwined on the walls of the palaces: symmetries, simple geometric patterns panned and rotated to give complex and refined motifs, 3-d puzzles that form muqarnas that seem to reach for the stars completed by floral motifs and Koranic verses that were not only carved but also painted with rich colors. Engraved into the decor are poetic inscriptions praising Allah and the sultans in rectilinear Kufic and cursive Arabic calligraphy crafted by different poets.

Indeed, in the last days of 1492, Queen Isabella entered the Alhambra on horseback, taking back the last Muslim territory in Spain, and ending Al-Andalus. While every mosque in town was replaced by a church, the sheer poetic beauty of the Alhambra deeply touched the Catholic monarchs. The palaces of the Nasrid sultans were preserved, and catholic kings added to them.

During the peaceful takeover, the last Nasrid sultan, Boabdil, handed over the keys and turned away. On a ridge now called El Suspiro del Moro (the Sigh of the Moor, with a beautiful view on the Moorish fortress), he looked back one final time and wept. His mother, and fervent patriot, Aixa al-Horra who followed him in exile to Fez, scolded him: “Weep now like a woman for a kingdom you have been unable to defend like a man!”

***

In Granada, history whispers through the labyrinthine alleys of the Albaicin, the soothing silence of ancient baths, and the secret viewpoints of Sacromonte. The timeless sophistication and elegance of the Alhambra that has seduced sultans and kings and mesmerized crowds to this day contrasts with the stories of resilience of the city’s blended cultures and faiths revealed in every bite of its fusion cuisine.

Granada is far more than the Alhambra, and best savored slowly. Let the tapas arrive as they do: unannounced, unexpected, and unforgettable.

Travel tips:

- Spain food Sherpas can organize gluten-free, vegan, and vegetarian food tours. Make sure to specify it when you book!

- Given the elevation, to enjoy the viewpoints, an e-bike is the way to go!

- Make sure to book your treatment at the Arab baths Hammam Palacio Nazari.

- To fully enjoy Granada, from the Albaicin to Sacromonte, the Alhambra and more, make sure to visit with Visit Granada, an excellent local tour company run by Maria Osorio, a passionate historian and guide.

- To visit the Alhambra, it is mandatory to buy tickets for a specific time-slot. Make sure you do so way ahead of time! Note that the entrance to the Nasrid Palaces is for the time-slot booked while you can spend the whole day in the Alhambra grounds and also come in and out freely.

- This article is also featured on GPSmyCity. To download this article for offline reading or create a self-guided walking tour to visit the attractions highlighted in this article, go to Walking Tours and Articles in Granada.

- Check out this interactive map for the specific details to help you plan your trip and more articles (zoom out) about the area!

Fantastic article!!! It brought back lot’s of gre

Thanks for your comment Heather! For whatever reason, it got cut off to “lots of gre” (assuming great memories)!