Text: Claire Lessiau

Photographs: Claire Lessiau & Marcella van Alphen

The old farmhouses and grain silos immediately give away the agricultural heritage of De Hoop Collection, nestled in the namesake nature reserve. Property of the VOC (Dutch East India Company) in the 18th century, its farms were available for loan to the free burghers—the VOC’s officials no longer in its employment.

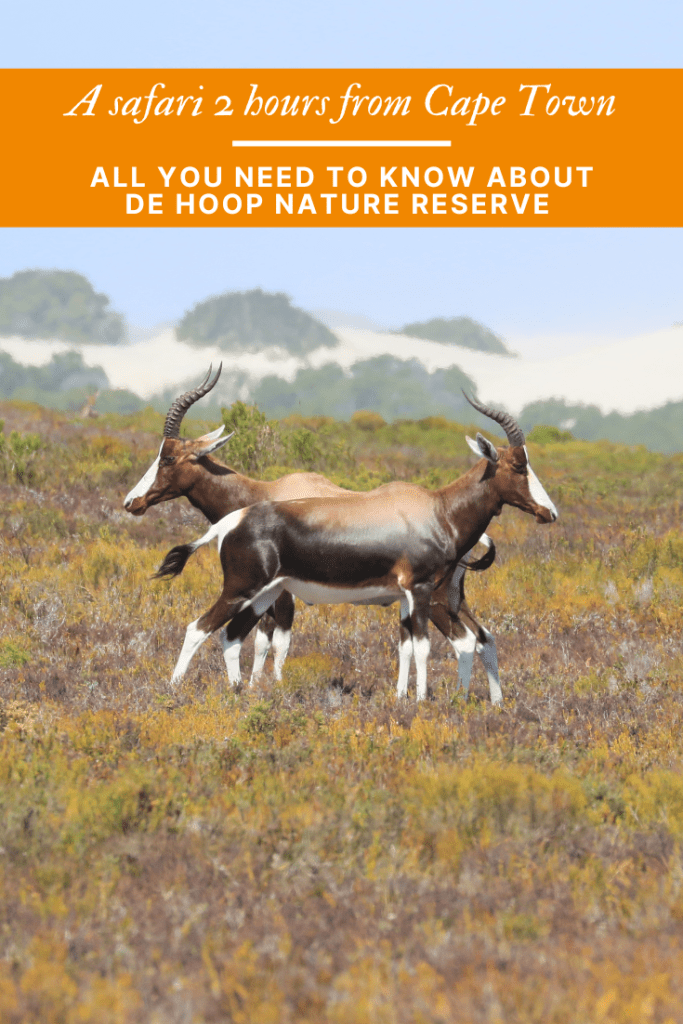

Pin it for later!

The original Manor House—now a luxurious and historical accommodation—still stands today in the centre of a 14,500-hectare-circle: per VOC rules, the boundaries of the farm were set by how far the farmer could horseback ride from a central point in an hour. In 1739, Frederick de Jager started farming, full of hope (hence the name) as he thought hope was probably the best nutrient to feed the crops given the poor limestone soils covered in Renosterveld—an endemic vegetation of grasses, mainly shrubs, and also small trees. However, Renosterveld soils are highly fertile, and wheat, merino, dairy cows, and ostriches were farmed on the estate. These fertile lands whetted the farmers’ appetites and in the Cape Floristic Region, less than 2 percent of Renosterveld vegetation is formally conserved—making this flora some of the most threatened types of vegetation in the world. The estate passed through several hands before the government acquired it in 1985 to conserve 360km² (89,000 acres) of land and 288km² (71,000 acres) of Marine Protected Area.

A historical estate turned a high-end accommodation

As I walk beneath a towering wild fig tree with its majestic trunk and pass a curious ostrich, I enter the charming Cloete Cottage, part of the historic farmstead. Seeking refuge from the biting wind and overcast skies, I step into the cozy warmth of the lime-washed room, where antique furniture creates a homey feeling. Outside, baboons, ostriches, and bonteboks who care for their young during this mid-summer do not seem bothered by the drizzle as they roam freely across the plains—former farming lands.

De Hoop Nature Reserve provides a safe haven for wildlife, with the largest predators being caracals and the elusive leopards.

Mountain biking Through the Precious Renosterveld

The following morning, the clouds break and the landscape is bathed in golden light. The weather changes very rapidly in the Overberg by the Indian Ocean. Just past sunrise, I set off on a mountain bike, traversing a part of the 500 hectares (1,235 acres) of Renosterbos shrub—a shrub named after the black rhino, whose diet once helped to spread its favourite food. Part of the Cape Floral Kingdom, the plant diversity at De Hoop reaches an incredible 1,500 species making it one of the highest in the region.

While the black rhinos have long since vanished, ostriches abound, opening their wings while running away to keep their balance as they see me approach.

Cape mountain zebras, an endangered species brought back from the brink of extinction and reintroduced in the 1980’s, graze peacefully nearby. Unlike the common Burchell’s zebra, their strong necks and distinctive black and white stripes that do not extend beneath their bellies are characteristic of the subspecies. The young foals still have small bellies as they feed mostly on their mother’s milk while the adults ruminate on grass as shown by their bloated bellies—and the unmistakable sound of processing grass when close-by! Undisturbed by my iron horse, I have the privilege of observing them for a while in one of the very few places where they can roam in their natural habitat.

The trails wind around the Vlei, offering an excellent opportunity to observe a myriad of water birds. Some venture towards the ocean, while other more technical mountain biking trails explore the inland wetlands. As I follow a winding single track, the early morning sun casts light upon fresh eland tracks. The characteristic direct register with the hinge leg stepping precisely where the front leg stepped has allowed these majestic herbivores, like all browsers, to navigate this terrain with minimal disruption. The way the dew falls only on the sand around the track indicates that they have been walking here after sunrise. After taking in the beauty of the veld and Vlei on this winding path the eland must question—the animal, sacred to the Khoi and the San who originally inhabited the region, is known for its efficient and safe path that used to crisscross Southern Africa—, I eventually stumble upon them by the bank of the Vlei. A magic moment!

Game Drives Through the Overberg

A guided game drive is the perfect way to deepen one’s understanding of the Renosterveld and its remarkable flora and fauna. As we traverse the sun-drenched plains, we spot herbivores grazing in the golden light of late afternoon. De Hoop is home to an impressive population of rare bontebok—approximately 3,000 left in the world, a tenth of which reside here. These were also brought back from the brink of extinction and are still vulnerable.

In the thicket, grey Makiri birds sing in duet. A bit further, a family of yellow mongoose pops in and out of their burrows that looks like a complex underground maze of galleries. A Cape mountain hare hops around in the shade as it seems to be waking up for its night round. A spotted eagle owl sits in a tree while a leopard tortoise crosses the Jeep track as fast as it can, giving me more than enough time to fully take it in!

As the open game drive vehicle comes to a halt close to a waterhole, not only the bonteboks take in the last sunrays, but also the majestic elands and some shy grysboks—an elegant antelope. Now that the engine is off, the sounds of the bush resonate. Meanwhile, our nature guide prepares a sundowner on the hood of his 4×4 with local biltong (a sort of beef jerky), samosas (a favourite Cape Malay snack), and the traditional gin & tonic that is here complemented by the De Hoop wines.

A Marine Walk Along the Marine Protected Area

De Hoop’s Marine Protected Area (MPA) stretches approximately 57 kilometres (35 miles) along the Indian Ocean coastline, extending 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) offshore. With about 250 fish species, this biodiverse stretch of coastline is one of the most important places along the 2,850-kilometre-long (1,770 miles) South African shoreline for southern right whales (Eubalaena australis). They mate and give birth in its sheltered bays each year between May and December—one of the largest nurseries worldwide for southern right whales. Pods of bottlenose dolphins often ride the waves.

I follow a small part of the multiday Whale Trail, a 55-kilometre-(34.2 miles)-coastal-hiking path to reach an inviting white sandy beach framed by towering cliffs. Shaped by the tides and the crashing waves, rock pools teeming with wildlife stretch into the Indian Ocean. The tides create an extraordinary range of conditions and extremely dynamic ecosystems for the ones who take the time to wade into the rock pools and focus on the small things.

In the nutrient-rich waters of Southern Africa, seaweeds and plankton flourish and there is an abundance of food for filter-feeders and herbivores such as mussels and limpets. Higher where the rocks get wet only during high tide for short periods, omnivorous periwinkles graze on black lichen mostly and will not pass on barnacle larvae. A bit lower some rocks get about an hour or two of wetness around high tide and the waves are calm. Limpets roam and use their iron-strengthened teeth—their iron-mineralized teeth are the strongest biological material studied so far—to scrape algae from the surfaces below. They return to their favourite homescar that fits them perfectly after grazing, competing against barnacles for space. Farther out, in a zone that is under water for half of each tide, mussels appear. At last where the wave action is hectic, soft-bodied animals like octopuses and nudibranchs thrive. Sea stars and sea urchins clean themselves with their tentacles.

Gulls wheel overhead, shrikes call from bushes, white-fronted plovers scamper along the sand pecking up morsels of food, and African black oystercatchers do what they are the best at (what’s in a name?!) even though oysters are getting rarer and the red-billed birds have turned to mussels.

A Boat Safari Through the Vlei

The Salt River once freely flowed by the farmstead into the Indian Ocean. About 200 years ago, the Boers planted trees close to the high dunes by the coastline to reinforce them, and little by little, the sand was blown into the river mouth, eventually closing it off and creating the Vlei—a wetland heaven for many bird species, including 97 types of water birds such as flamingos, pelicans, spoonbills…

As our flat-bottomed boat glides quietly through the Vlei, red-knot coots take flight, their presence a sign of the excellent water quality here. In the distance, a fish eagle perches atop a milkwood tree, while a darter hunts for fish along the bank. White-breasted cormorants dry their wings in the sun, and weavers diligently construct their nests. White-fronted swallows are hitching a ride on the floaters of our boat.

As our guide steers the boat closer to the shore, we notice holes above the water line. They are nesting sites of many types of kingfishers. The pied kingfisher—the only species of kingfisher that is polygamous—, unique for its communal breeding habits, shares its nesting sites with other species, such as the colourful malachite kingfisher that sits on a branch next to a smaller hole.

***

While De Hoop may not carry the excitement of the Big 5 most international tourists are after, the nature reserve provides a safe environment where endangered species can be observed at close range. The variety of landscapes from land to sea can be enjoyed in a vehicle of course, but also simply walking or biking, making it all the more special to stumble upon wildlife.

Travel tips:

- The De Hoop Collection provides a wide range of accommodation from campgrounds to the luxurious historical cottages, and self-catering units (even though it would be a shame to miss out on the good onsite restaurant).

- The excellent “Origins of Early Southern Sapiens Behaviour” exhibition is hosted at De Hoop Collection and is really worth a visit.

- Check out our interactive map for more in the area (black pins lead to an article):

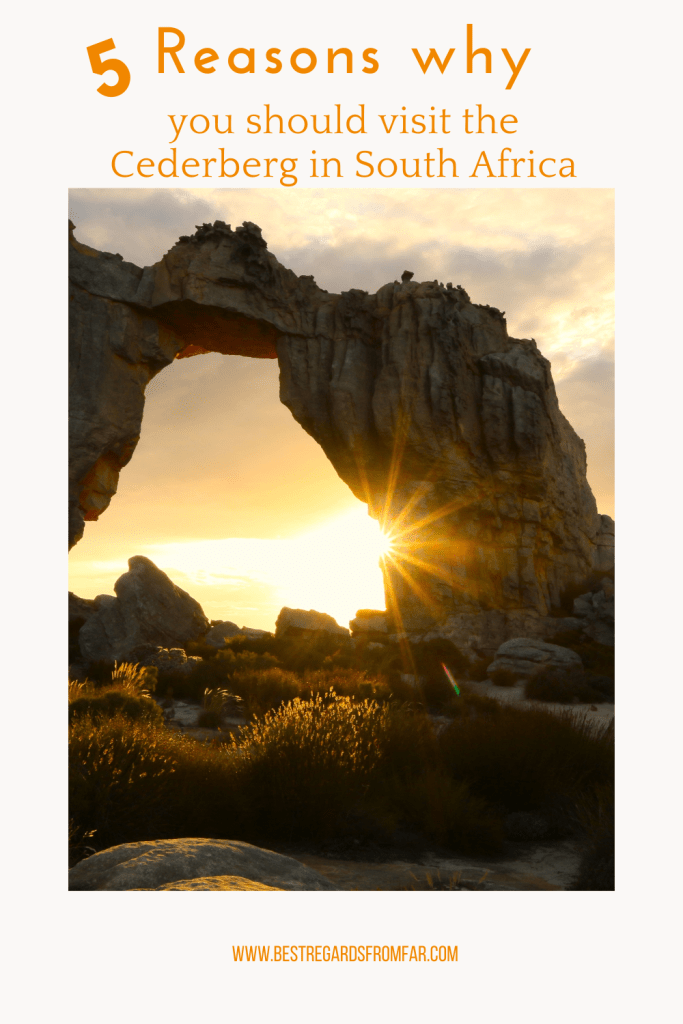

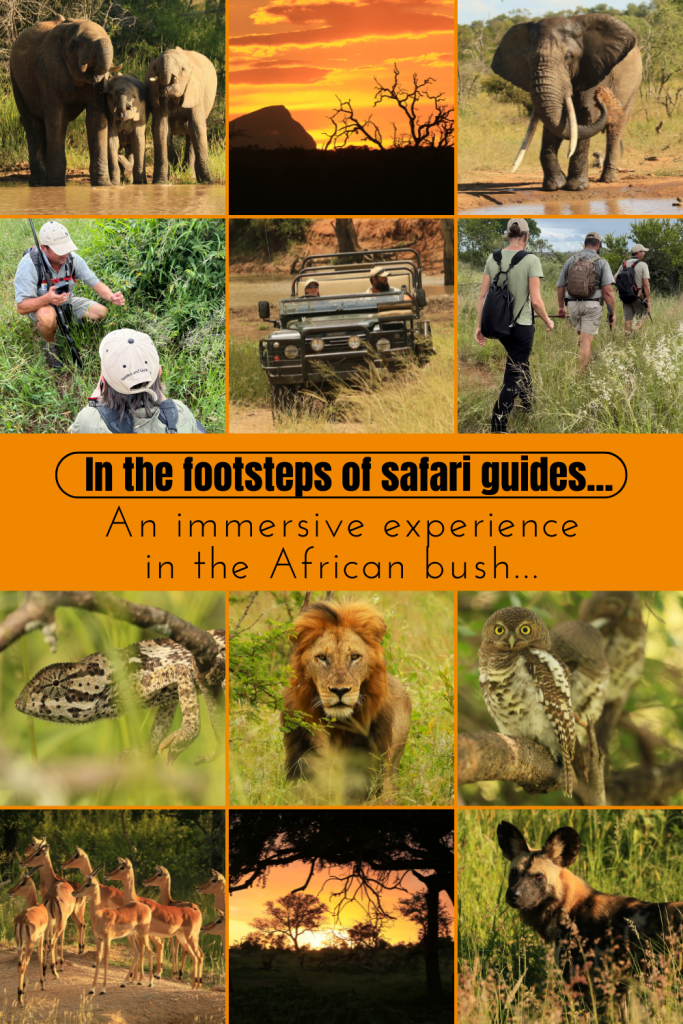

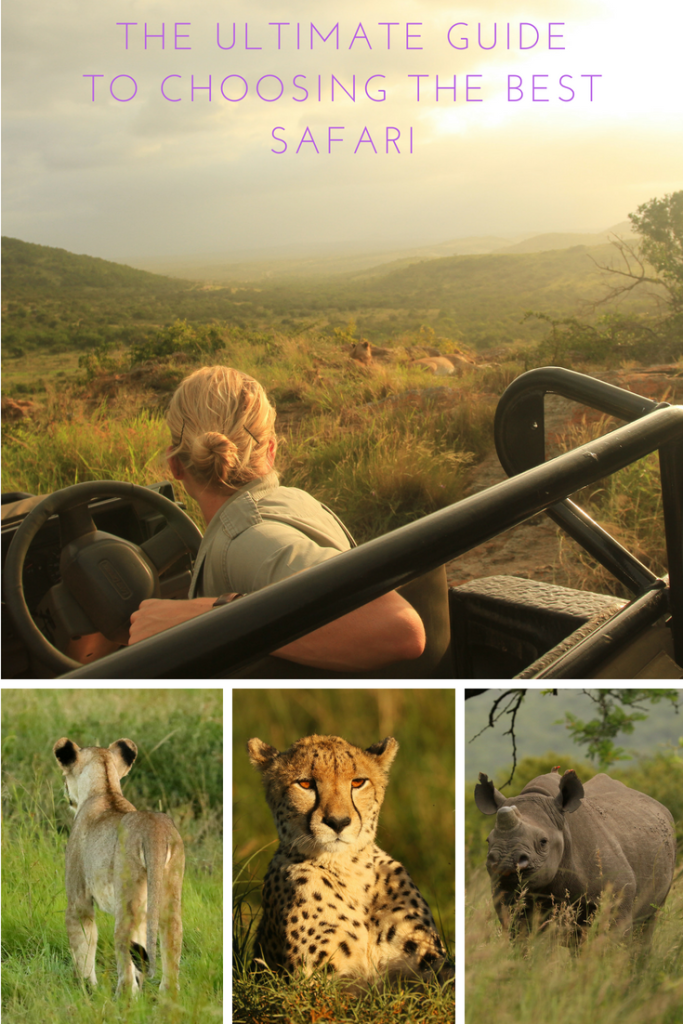

For more in the Western Cape, click on these images:

Fantastic article! Hugs,HeatherSent from my iPhone

Thanks! There is so much more in South Africa that you would love. You need to come back!

Well written.. thanks for the share

Thanks! Would love to write about Uganda soon 🙂